This all started when my Mom was exposed to radiation and developed a super-power.

Seriously.

At 58, my mother was treated for cancer with injections of radioactive iodine. When it was over, her cancer was gone, but she’d developed an unnaturally acute sense of smell, which seems to be permanent. She soon became fascinated with perfumery and aromatherapy, and one day asked me, “How do you capture a natural fragrance?”

The trick is called steam distillation, and it’s little known today because the fragrance industry has replaced the independent perfumer, who used to sweat in solitude over a bubbling basement still. But in 18th-century France, the perfumer’s knowledge of steam distillation amounted to a kind of practical alchemy — the ability to capture a beautiful, ephemeral sensation and preserve it for sale.

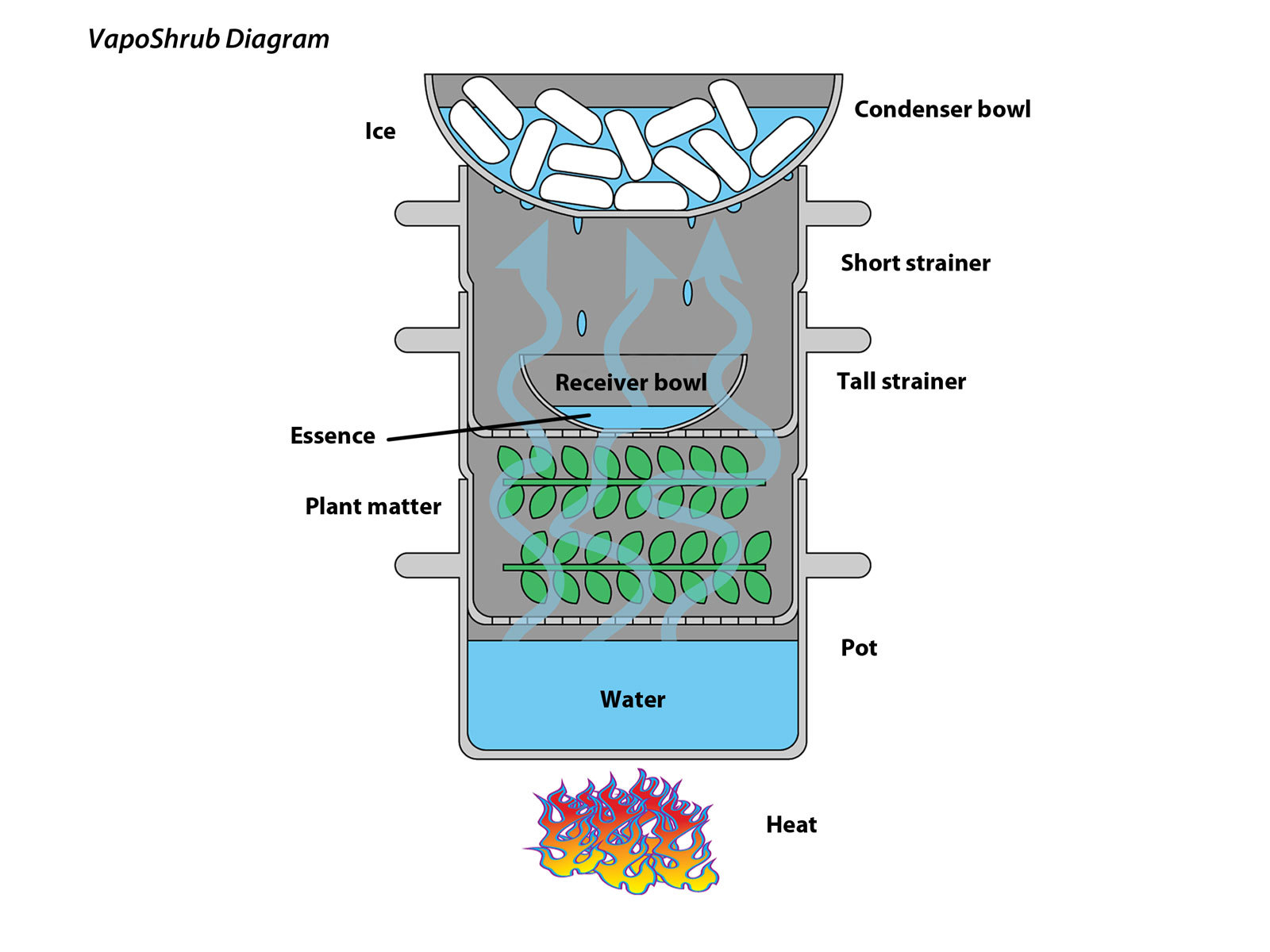

Here we extract the earthy scent of rosemary, but almost any fragrant plant should work well for this project. The technique is simple: steam rises through a strainer full of plant matter, vaporizing volatile oils and other fragrant compounds, which condense on an icy bowl and drip into a small receiving bowl. Start your essence!

CAUTION: Do not use glass cookware in this project unless you understand how to prevent breakage due to thermal shock. Even borosilicate glass can shatter explosively if heated or cooled too rapidly. Also, be very careful to avoid steam burns while inspecting the still and/or emptying the receiving bowl.