My 4-year-old son comes up with some funny ideas. A few months ago, he asked for a piece of cheese to leave outside for animals. We gave him a slice of cheddar. The next morning he jumped out of bed and hurried to the window. The cheese was gone, but who had taken it? He was guessing all day. We looked for footprints or tiny hairs, but found no clues.

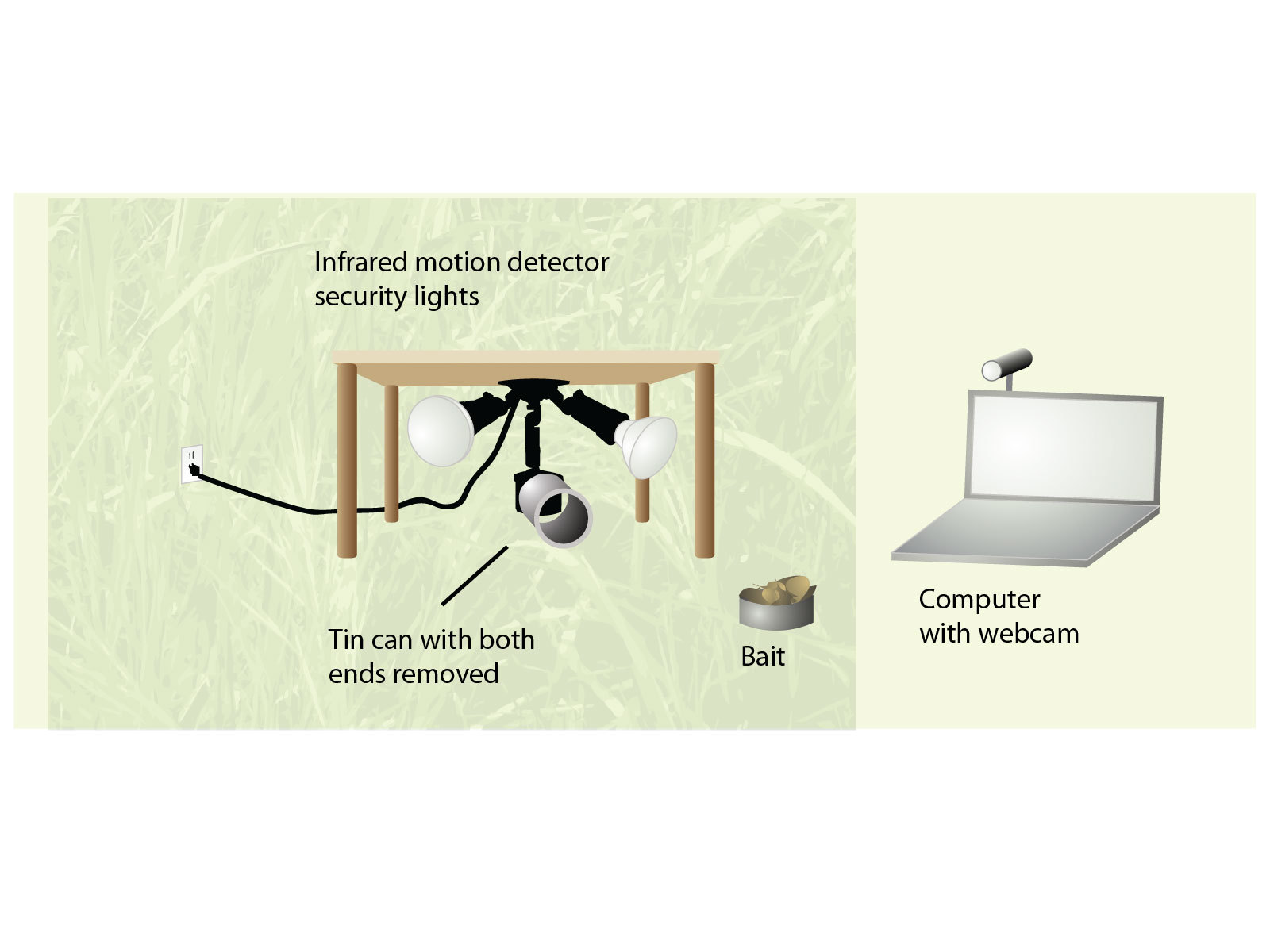

Then we got more ambitious. I knew that some webcam programs can record video only when there’s visible motion. That might record visitors in daylight, but not in the dark. So we got an inexpensive infrared-sensing floodlight — a standard home security device — at a hardware store. I figured that in theory, a warm animal moving in front of the device should make the light turn on, and then the webcam program would see movement and start recording.

That evening we tested it, with the webcam pointing out a window and the floodlight just outside. The next morning, my son and I raced to the laptop. A white cat had visited at 4:30 a.m., and the video caught it flinching as the light came on, looking quizzically at the contraption, and then starting to eat. My son was fascinated, and we were both hooked on our new hobby.