It was December of 1985 when I watched in horror as my father began ripping apart my favorite toy. Teddy Ruxpin, for those unfamiliar, was an animatronic storytelling teddy bear that was a close friend to many children of my generation. When an official Teddy Ruxpin cassette tape was inserted into his back, he would spring magically to life, blinking his eyes and moving his mouth to speak in a gentle, non-threatening voice. My dad was certainly sick of hearing Teddy sing songs and regale me with tales of high adventure, so he had decided to add a custom headphone jack and spare his sanity.

While I feared for my animatronic friend as he went on the operating table, I was fascinated as my dad explained the inner workings of the bear. The audio cassette tape contained two tracks: one reserved for the voices and music, and the other containing audio frequencies that told the circuits how to move the mouth and eyes in perfect synchronization. It was all pre-programmed. There was no magic involved.

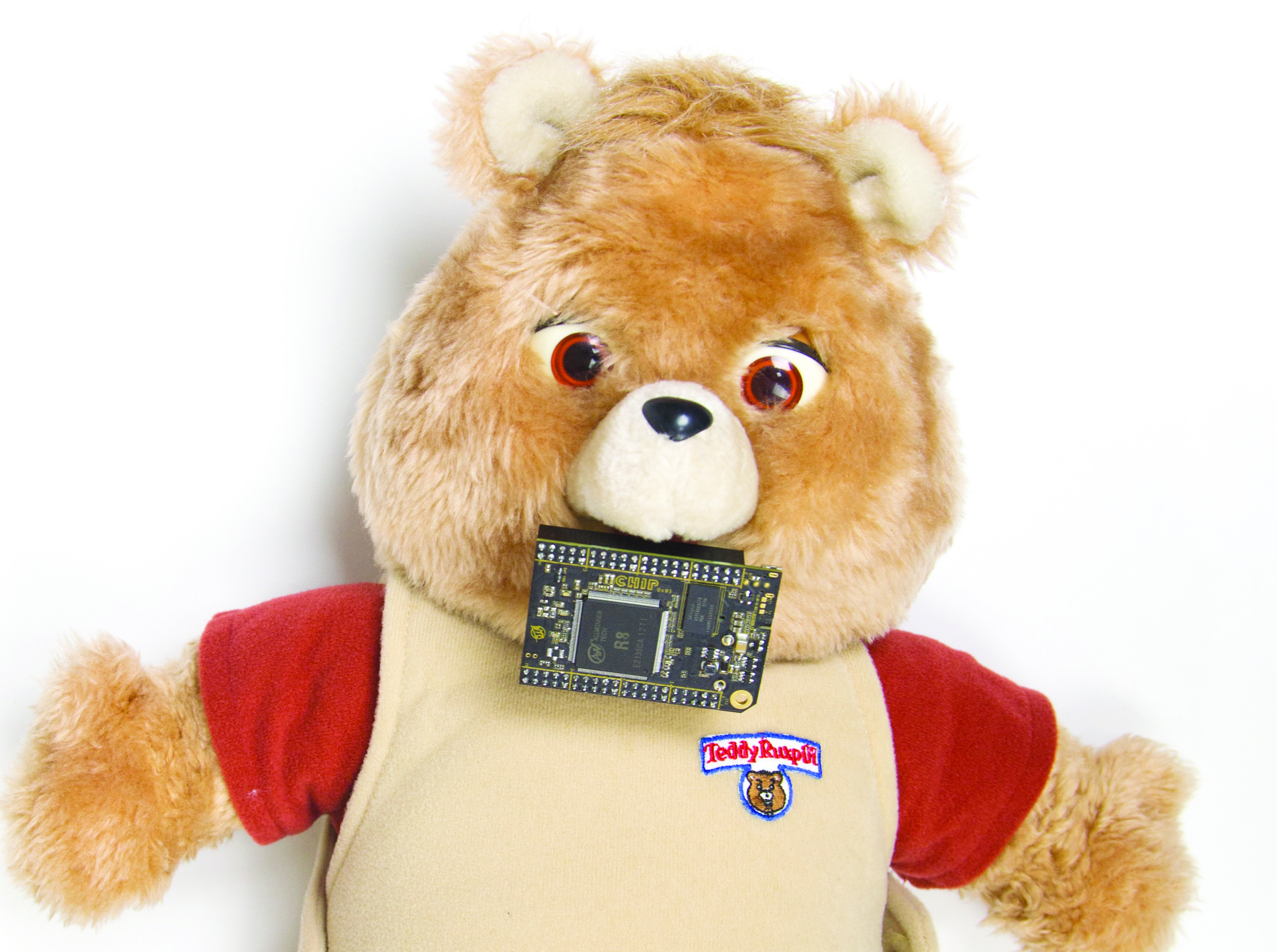

More than 30 years later, I found myself at Next Thing Co., brainstorming ideas of entertaining things we could make with C.H.I.P., the world’s first $9 computer. Remembering back to that cold December afternoon, I suggested we hack a Teddy Ruxpin so we could control him over Wi-Fi and make him say whatever we wanted. Maybe read us tweets. Why not?

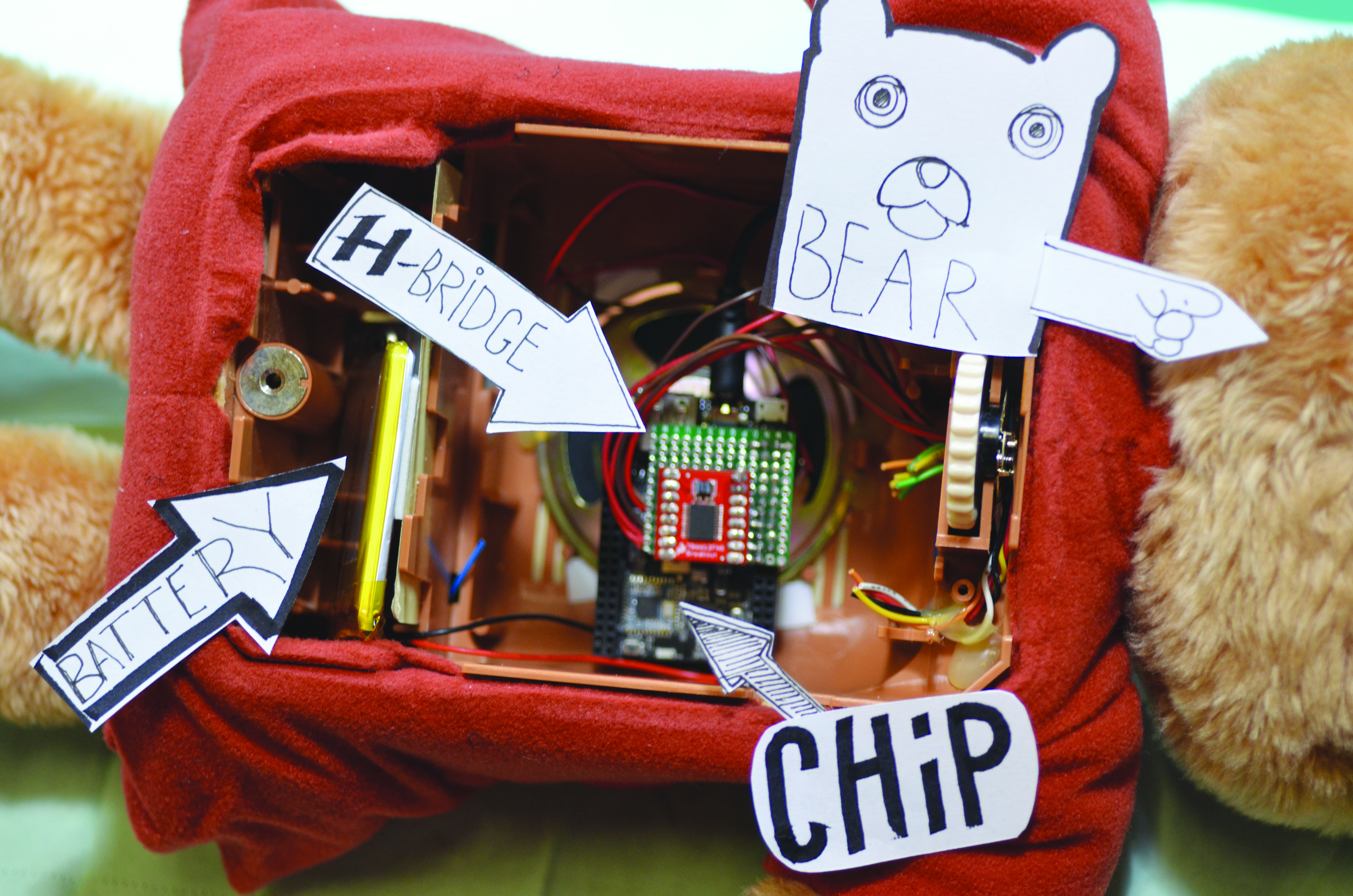

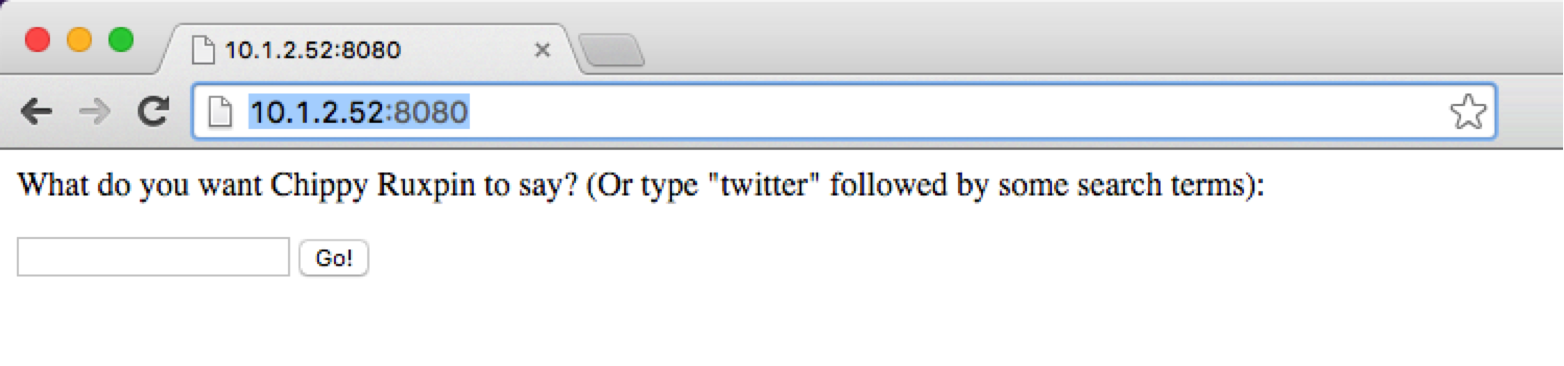

Thus, the goals of the project were established: C.H.I.P. would log on to your existing Wi-Fi network and present a custom web page with a text box. Users would type what they want the bear to say, or tell him to read Twitter messages based on specified search terms. A text-to-speech engine would be utilized to read the results out loud and automatically move the mouth to perfectly match the voice. All of this would be powered by a 3.7V LiPo battery, using C.H.I.P.’s built-in charging circuit through a micro USB connection.

2. Original speaker plays speech and other audio.

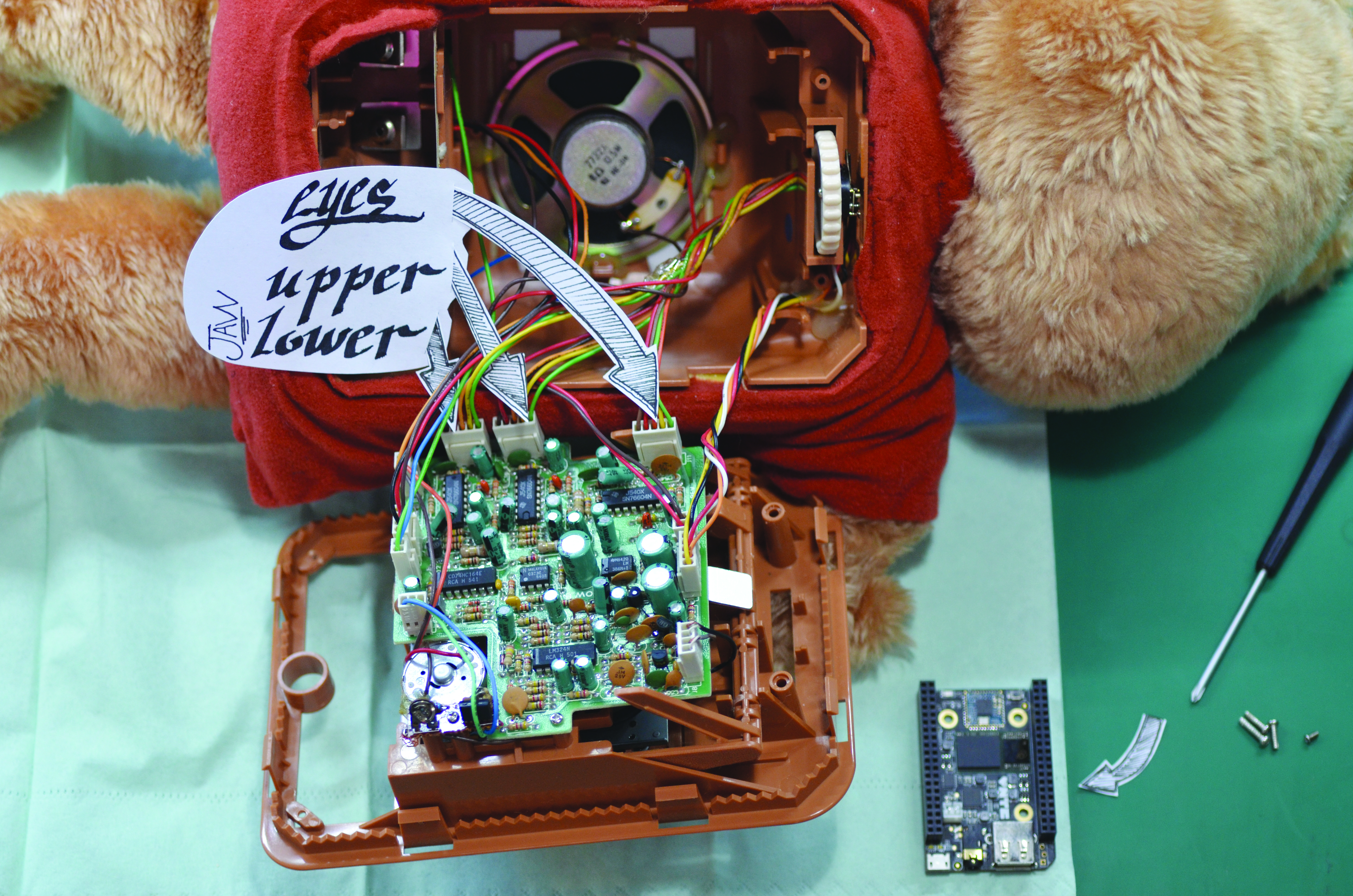

3. Remainder of Teddy’s antique guts are removed: circuit board, cassette tape drive, audio/data cassette, and 4 hefty D batteries.

4. C.H.I.P. computer connects to internet via onboard Wi-Fi, then converts incoming text or tweets to speech and sends it to the speaker, while analyzing audio amplitude to create synchronized motor signals.

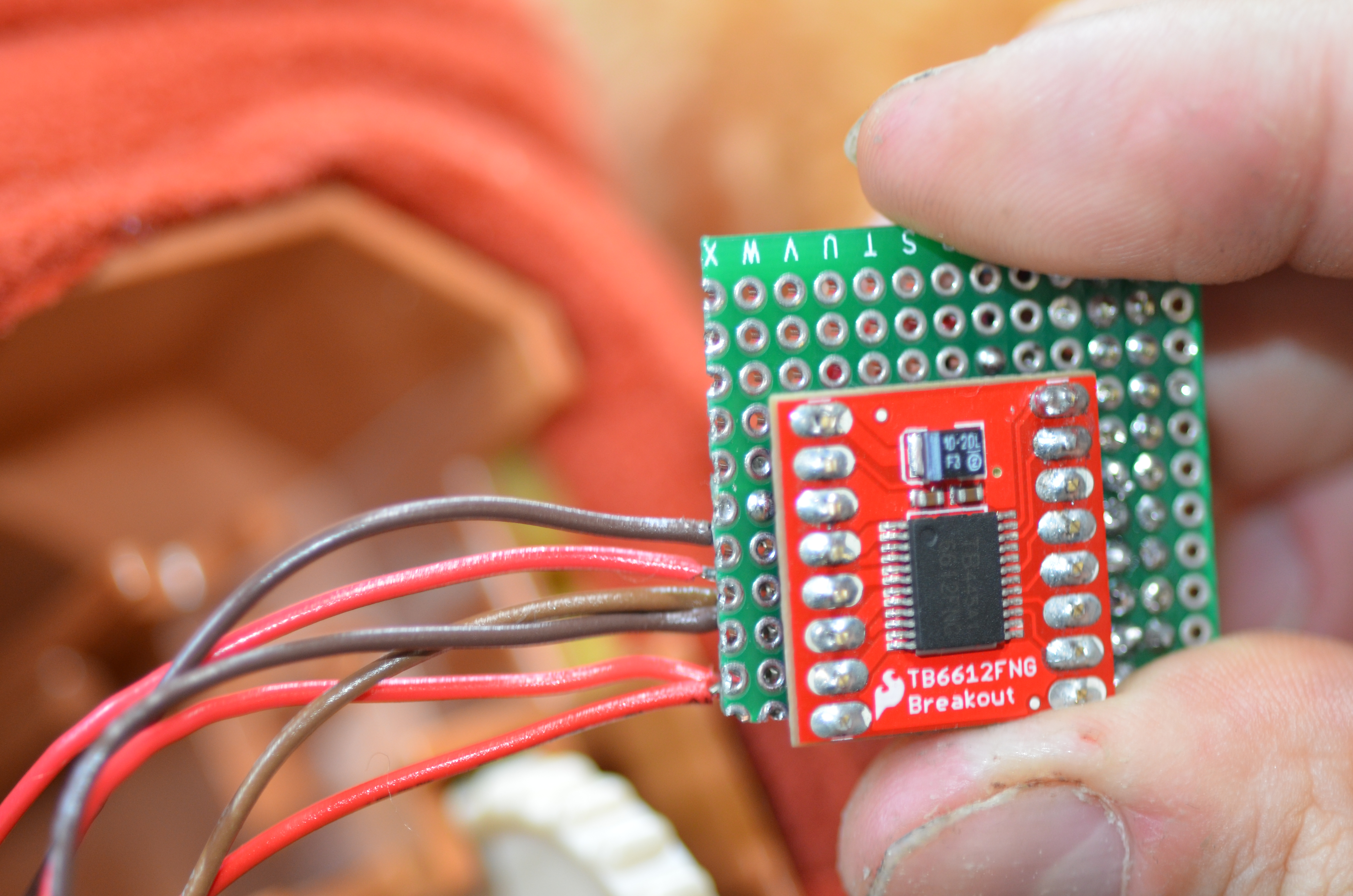

5. H-bridge motor controller board on a DIY “shield” plugs into C.H.I.P. and drives the original servos.

6. 3.7V LiPo battery plugs directly into C.H.I.P. to power everything.

Illustration by Damien Scogin