Behind the lens of a webcam is an imager chip with thousands of tiny light sensors, each about 1/10 the diameter of a human hair. If you replace the lens with an LED light source, and place tiny objects on the imager chip, shadows will project onto the sensor, creating a lensless microscopic image. You can use the webcam’s regular software to save pictures and video, or stream live images to the internet. Or use the imager chip from a security camera to see a colony of live plankton on TV.

Projects from Make: Magazine

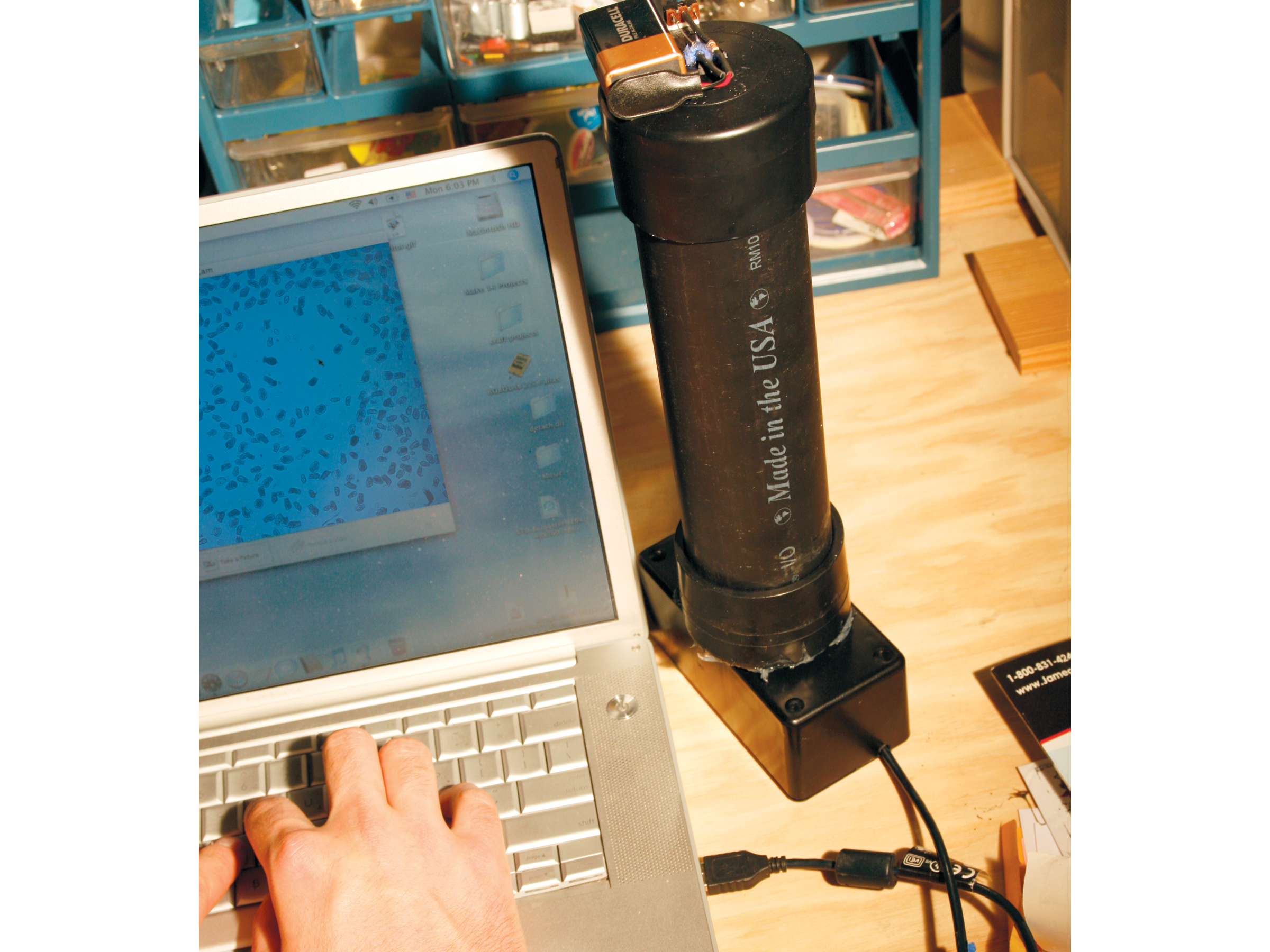

Lensless Microscope

Use a webcam’s image chip to create an ultrafine shadow-imaging stage.