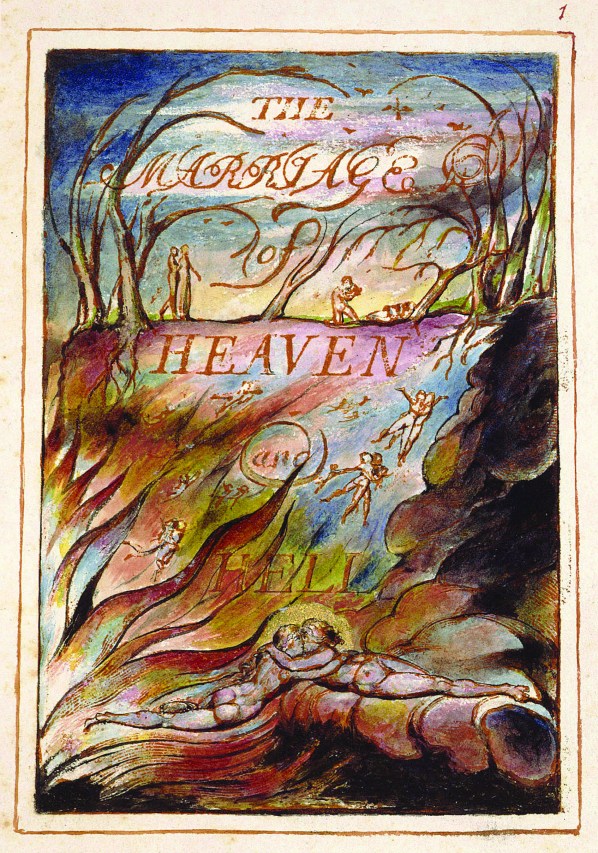

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Copy I, 1827), an early example of Blake’s invented technique of illuminated printing and something of a proto-zine, with different writing styles, voices, postures, rants, and aphorisms.

For the past 25 years, nearly every day, I’ve interacted with “the mad English poet” William Blake in some fashion. I poke my nose into one of the dozens of books I’ve lovingly collected, or I whisper (or shout to the rafters) a poem, or I chew on some gristly hunk of his ridiculously complex poetic psycho-mythology.

For someone with the attention span of a 4-year-old, having anything captivate me to such an extent is downright alarming. Equally strange is the fact that I rarely explain my obsession with Blake to anyone.

Why am I so fascinated by this apocalyptic, outsider artist (in his day) whose work still defies comprehension? What keeps me coming back?

In this article, I’ll explain a little of Blake’s invented printing method, and make my case for him as patron saint of makers.

William Blake, 18th-Century Zine Publisher

I was introduced to William Blake in British Lit class in high school, but ironically, it was during the desktop publishing revolution of the mid-1980s that I started to understand what he was really all about.

I came to the real Blake by way of the cyberneticist Gregory Bateson. Bateson was fascinated by how Blake famously “mixed up” modes of perception in his work; Blake claimed he had something called “fourfold vision” and that he could see things on different levels of awareness simultaneously.

Bateson had studied schizophrenia for the Veterans Administration and discovered that, similarly, schizophrenics confuse and conflate, for instance, the literal and the metaphorical; they don’t organize thoughts, communication, and perceptions into logical categories the same way that non-schizophrenics do.

Blake also seemed to leak at the margins separating these logical types. Of course, one can argue that all artists do this, but it’s the extremes of the leakage in Blake’s work, the sheer quantity, and its complexity (and its surprising coherence, if you stick around long enough to sort it out) that makes Blake so compelling. Bateson was also intrigued by how functional Blake was while living in his world of perceptual and categorical mashups.

As I began to delve deeper into Blake, one day I had something of an epiphany. I’d gotten a lovely two-volume set of his most popular works: Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, two of his masterpieces of “illuminated printing,” a technique of free-form engraving, painting, and printing he’d invented.

Up until his discovery, illustration engraving and book printing were two separate disciplines, with the engravings etched, printed, and later, tipped into the books as plates. By combining these two arts on the page, Blake’s technique freed him to write text, compose pages, design typography, and paint illustrations, right on the copper printing plates.

I was reading about all of this while working on a zine publishing project, using an Apple Mac SE running PageMaker layout software. I was doing a lot of the writing, designing, even some of the illustrations, right in PageMaker, and printing out my zines on the Canon copier sitting next to my Mac. I realized that Blake had experienced the power of a different, but surprisingly analogous, set of media tools and felt a similar sense of creative freedom, more than 200 years earlier. William Blake was a zine publisher! William Blake was a multimedia artist!

“On England’s Pleasant Pastures Seen”

William Blake was born on Nov. 28, 1757, in Soho, London, in a modest apartment above his father’s hosiery shop. His parents were devoutly religious, but they were Dissenters, nonconformists who opposed the established Church of England and its hierarchy. From an early age, Blake proclaimed religious visions, that he could see angels and other nonphysical entities. His father tried to beat such nonsense out of him.

Aside from punishment for seeing apparitions, Blake’s early childhood was rather peaceful, even bucolic, as he wandered through fields on the outskirts of London, swam in farm ponds, haunted printmakers’ shops, read the classics and the Bible, and studied as much art as he could find.

The rest of his life found him living through some of the most tumultuous times imaginable, including the American and French revolutions, great scientific and naturalistic discoveries, the dawning of the Industrial Revolution, and all the intellectual ferment and cultural activity excited by these seismic shifts.

It’s no wonder that Blake’s subject matter was so epic, so apocalyptic — all fire, upheaval, and psychic magma on one hand, and Eden-like dreamscape on the other. He saw tremendous potential in humanity and in the power of big ideas — and he dreamed of all of it coming to flower in his beloved Albion.2 But he also saw the horrors of war, of poverty and class division, of state and religious intolerance, and of the shortcomings of science and reason when divorced from imagination and wonder.

Blake showed artistic promise at a very young age and was enrolled in drawing school at age 10. At 14, his father, ever the pragmatic tradesman, wanted his son to know a durable trade, so he signed him up as an engraver’s apprentice, where he labored for seven long years. It was as an engraver that Blake developed a lifelong love for Gothic art and architecture and for the nobility of the engraver’s and printmaker’s arts (though he resented being forever identified solely in that trade).

In 1779, at 21, Blake was accepted into the recently formed Royal Academy of Arts. He quickly found himself at odds with the teachings of the school and its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds would become a lifelong artistic foil for Blake, a two-dimensional symbol of everything he found wrong about establishment art and art that generalizes, abstracts, and handily categorizes; art that no longer “rouses the faculties to act.”

Blake Dreams a New Method of Printing

In 1788, Blake claimed he’d been visited in a dream by his dead brother Robert (who’d recently died of consumption) and shown a revolutionary new printing technique.

Unlike traditional engraving, where the image outline is scratched into a plate prepared with an acid-resistant waxy “ground” and then the lines are exposed to acid, Blake’s technique worked in reverse. The area to be printed was painted over with the acid-resist ground and then the plate was exposed to acid, eating away everything that was not the image.

After etching, he would touch up the image and clean the copper plates with his engraver’s tools before printing the pages on a rolling press and then (usually) coloring the printed pages with watercolors.

For Blake, “illuminated printing” was the artistic breakthrough of a lifetime, “a method of combining the Painter and the Poet.”

Anyone who’s looked closely at traditional engraving tools and techniques can appreciate how painstaking, labor-intensive, and constraining the process is (a square inch of engraving can take hours). Now, imagine a method of engraving that combines text and artwork, where creation happens right on the plate, using pens and brushes, traditional artist’s tools.

Imagine how excited Blake must have been by this discovery. Unlike traditional engraving, which was largely a copyist medium, a means of reproduction, illuminated printing was a means of original production where you could compose your ideas, and paint them, right on the printing plate.

To give you a better idea of how illuminated printing worked, here are a series of photos taken by Todd Weinstein in 1979 in the New York studio of Blakean scholar Joseph Viscomi. They were part of Viscomi’s attempt at preparing, executing, and printing a relief-etched facsimile of plate 10 from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790). Blake wrote little about his technique, so his process is not exactly known. Few of his plates survive. Tragically, they were mainly sold for scrap metal after his death. Scholars such as Viscomi have managed to reverse-engineer the process and they think it went something like this.

From the Heart of Los’ Forge: Preparing the Metal

In Blake’s psycho-mythology, his inner poet/creative man was named Los (likely “Sol” spelled backward). Los is a blacksmith, and given the preparations required to create the plates that Blake worked on, it’s not hard to see how he would have made the connection between this prep work and the roots of his creations, both literally and figuratively. Copper sheets had to be hammered and cut into smaller plates, planed, washed, oiled, and polished.

Raising Up His Voice: Painting the Text and Art

Once the plate was prepared, Blake painted the text and artwork onto the copper surface with quills and brushes, using an “impervious fluid” that would resist the acid to which the plate would then be subjected. For this, he used “stop-out,” an asphalt-based varnish found in traditional engraving, used to cover already-etched lines to prevent them from being further “bitten” into during successive etchant baths.

Because the designs would be transferred onto paper in an engraver’s press, the art and text all had to be painted in reverse. While Blake was already used to reverse composition in engraving, he raised free-form mirror writing and mirror painting to an art form in itself. (For a man who believed it was a mission for each of us in life to do everything in our power to keep our minds awake, our imaginations expansive, and to look at things from multiple points of view, conceiving and visualizing everything backward must have been a great “mind hack” in support of this worldview.)

“Melting the Metals into Living Fluids”: Etching

With the image painted onto the copper with impervious liquid, Blake would then create a dike around the outside edges of the plate with walls of soft wax. This allowed him to pour a bath of “aqua fortis” (nitric acid) onto its surface. As the corrosive acid bit into the exposed metal, Blake would hover over the plates like some Shakespearean witch, using a big bird feather to keep the acid agitated and to stir away bubbles that formed.

The process, with its noxious fumes, was not a pleasant one (some have suggested that the liver failure that finally took Blake’s life may have been the result of “chronic copper intoxication”). It’s no wonder that he called this an “infernal process,” and that in his satirical masterpiece, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he located his print shop in hell.

With his penchant for leaking margins between modes of perception, Blake proclaimed that what he was really doing in his artistic process was “melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.”

After the etching was complete, he would remove the acid and the wax dike, rinse off the ink with turpentine, and polish the plate before inking.

“Without Contraries Is No Progression”: Inking

Ink was applied to the etched copper plate with a flat-bottomed linen dabber wetted with engraver’s ink. The ink was made of a powdered pigment mixed with burnt linseed or walnut oil. For multicolored prints, Blake would use smaller dabbers or brushes to apply spot colors to desired areas on the plates.

“In Which Knowledge Is Transmitted from Generation to Generation”: Printing the Plates

Blake’s wife, Catherine, was his assistant in hell’s printing house and she was especially adept at printing, and in hand-coloring the printed pages. They used an engraver’s press (with the plate and paper on a bed that passes between two heavy rollers when the press is cranked). Blake would ink and deliver the plates to the bed and Catherine would then place the paper, blankets, and backing sheets.

Given the metalwork, caustic chemicals, oily inks, and other “infernal” parts of the process handled by Blake, and the pristine and expensive white paper delivered by the lovely Catherine, it’s no wonder that he saw their extreme roles as a symbolic expression of the dynamic, two-toned life process, his “marriage of heaven and hell.”

“Exuberance Is Beauty”: Hand-Coloring the Prints

For his illuminated books, Blake and Catherine would hand-color the printed pages with watercolors to complete an edition. Some editions, and individual copies, were painted very simply, others far more elaborately.

Over the years, Blake also changed, sometimes dramatically, the ways he colored the manuscripts. This could depend on his mood, or whether he desired to bring out some aspect of the work in a specific copy he was creating. This has allowed connoisseurs of Blake’s work to enjoy, interpret, and heatedly debate multiple versions of the same work from countless perspectives, something Blake surely would have been thrilled by.

Create! The End Is Near!

During his lifetime, Blake was uncompromising in his work and what he wanted to say with it. His art is so dramatic, so muscular and apocalyptic, because he felt an overwhelming sense of urgency. One can almost picture him as a crazy man on a street corner, wearing a sandwich board, waving around dirty fistfuls of doomsday pamphlets.

But instead of proclaiming “Repent, sinners! The end is near!” Blake’s message was more like: “Wake up! There’s an artist asleep inside of you! Don’t let the world lull you to sleep. Create!”

And that message, steadfastly encoded like a fractal equation, reiterating at every level of his work, is what makes William Blake a worthy saint of makers. He called his illuminated prints “windows into Eden.” They were designed to function something like stained glass: you can see through them, to something on the other side. What he hoped you’d catch a glimpse of there was your own creativity, your own “poetic genius.” Blake didn’t want to create work for you to passively consume; he wanted to create work that would inspire you to make something yourself!

Blake’s early biographer Alexander Gilchrist said: “Never before surely was a man so literally the author of his own book.” Blake was self-taught in every discipline but engraving; during his lifetime, he was a painter, poet, essayist, author, inventor, philosopher, engraver, printer, calligrapher, graphic designer, bookbinder, singer, songwriter, and metalsmith (to name a few). One of Blake’s best-known quotations is, “I must create my own system or be enslaved by another man’s.” There is no more ultimate “maker” statement than that.

SPECIAL THANKS: Information about Blake’s printing technique used in this article comes from the article “Illuminated Printing” by Joseph Viscomi, available at the William Blake Archive (blakearchive.org). Many thanks to Professor Viscomi for providing these images.

See larger versions of the illuminated printing process photos, and check out our own experiments in recreating the technique, at makezine.com/17/blake.

Channeling Your Magic Cephalopod

I can’t think of a better example of a real-life Blakean character, someone who’s cultivated a similar self-modeled universe and who sees things from many unique angles, than contemporary comic artist and memoirist Lynda Barry.

This is impressively evident in Barry’s new book, What It Is (Drawn And Quarterly, 2008). This densely collaged work is utterly uncategorizable — so many simultaneous modes of expression: a textbook/workbook on inspiring creative writing and cultivating creativity of all kinds; a memoir-comic of Barry’s personal struggles with creativity and self-expression, especially as a child; a stunning, intense, and challenging piece of collage/altered book art; and a sort of extended fever dream on the nature of memory, imagination, play, and creativity.

Like Blake, Barry’s message is also about rousing yourself from creative slumber. It’s an extended pep talk on finding your sources of inspiration and using your senses and memories of life experiences to express yourself in ways that can truly enrich your life.

When you open up this book and poke your head into its dream-like sea of memory-ticklers, imaginative ideas, creative inspiration, and surreal imagery, it’s hard not to want to put it down and go make something on your own. As if to drive home the beastly, manifold nature of primal creativity, Barry introduces the Magic Cephalopod (aka squid), a sort of creature from your id who swims through the murky depths of the text, its many appendages in constant creative motion, gently guiding you to swim off on some grand adventure inside the Mariana Trench of your own creativity.

This is Blakean art, and Blakean inspiration, for the 21st century.

ADVERTISEMENT