Charles Goodyear may have been the most dogged and unrelenting solo inventor of the 19th century’s golden age of invention. His was an interesting life, a wild roller coaster of ups and downs, although unfortunately mostly downs.

Goodyear was not wealthy or wildly successful. Many people are surprised to learn that he did not start, work at, or even know of the giant industrial concern called the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. The company, which was named in Goodyear’s honor, was founded in 1898, about 40 years after Goodyear died.

The Early Years of Rubber

In the winter of 1820, a rubber fad swept across America when millions of people bought rubber-coated boots to keep their feet dry. But the fad ended as abruptly as it started when consumers found that a single summer of hot weather turned their rubber shoes to mush. Natural rubber clothing just wasn’t durable or practical.

At that point Charles Goodyear entered the scene. Goodyear thought that if he could figure out a way to toughen the rubber chemically he would have a product that people would buy. Although he knew almost nothing about chemistry, engineering, or business, he was, like the substance he was trying to make, resilient and tough.

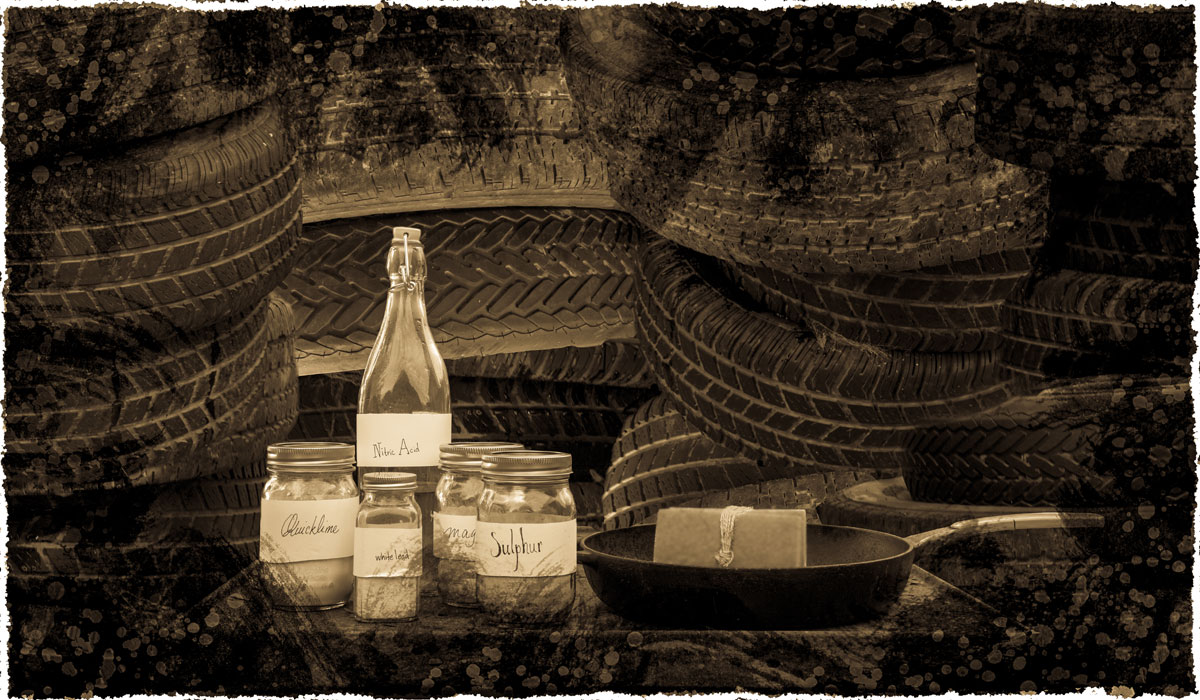

He began to experiment with latex. He mixed in witch hazel, magnesia, even cream cheese in attempts to turn sticky, soft latex into durable, tough rubber. Nothing worked. He got close a number of times, but was not able to develop a repeatable process that would turn rubber into a useful raw material.

He kept trying until he had spent all his money, so he borrowed some. He spent that and borrowed more. Eventually, he and his family were broke and living on the charity of his friends. Things looked bleak.

The Lucky Accident

Then an accident changed things. On a cold winter day in 1839, Goodyear inadvertently brought a piece of rubber that he had treated with sulfur into contact with a hot stove. The inventor looked at the piece in amazement. The hitherto gummy yet fragile compound had become something wonderful.

Goodyear’s rubber fragment did everything that natural latex could not. It had become, in modern parlance, vulcanized. It was tough and durable in hot weather, and stayed flexible in cold weather. This, Goodyear knew, was a product with a huge future. By the winter of 1841, things were looking up. Goodyear’s new process was an astounding success, and money started to come his way.

But sadly Goodyear was not a capable businessman. While he did obtain a patent for the vulcanization process in 1844, he licensed the process at rates that were far too low for him to make money. Worse, when patent infringers stole his work, he spent more on his attorney’s fees than he was able to recover from the pirates.

He spent the rest of his life attempting to make good his dream of becoming a millionaire rubber manufacturer. Goodyear staged magnificent displays showcasing rubber products including furniture, floor coverings, and jewelry at London and Paris exhibitions in the 1850s. But while in France, his French patent was can-celled and his royalties stopped, leaving him with outstanding bills he could not pay. Goodyear was thrown into a debtors’ prison.

When he died in 1860, Charles Goodyear was $200,000 in debt. Posthumously, royalties on his process started to roll in. His son Charles Jr. later made a fortune manufacturing shoemaking machinery. It’s a shame that Charles Sr. never enjoyed the financial success his invention ultimately provided for his family.

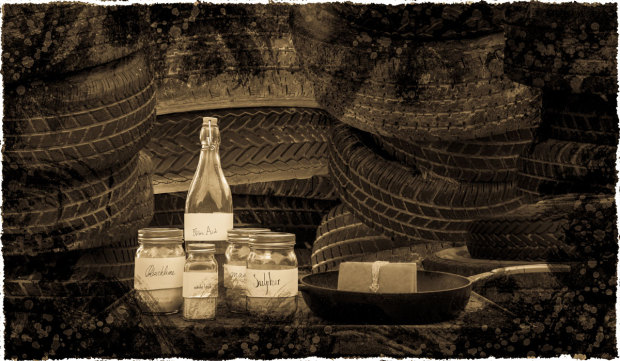

Make a Rubber Eraser

You can re-create the process of vulcanization using a modern product to make your own rubber items, like these pencil erasers in a shape you might recognize. We think Mr. Spock would appreciate them.