Patrick Flanagan invented the “Neurophone” over 40 years ago. His original patent (US3393279) was basically a radio transmitter that could be picked up by the human nervous system. It modulated a one-watt 40kHz transmitter with the audio signal, and used very near-field antennas to couple it to the body. It also used extremely high voltages.

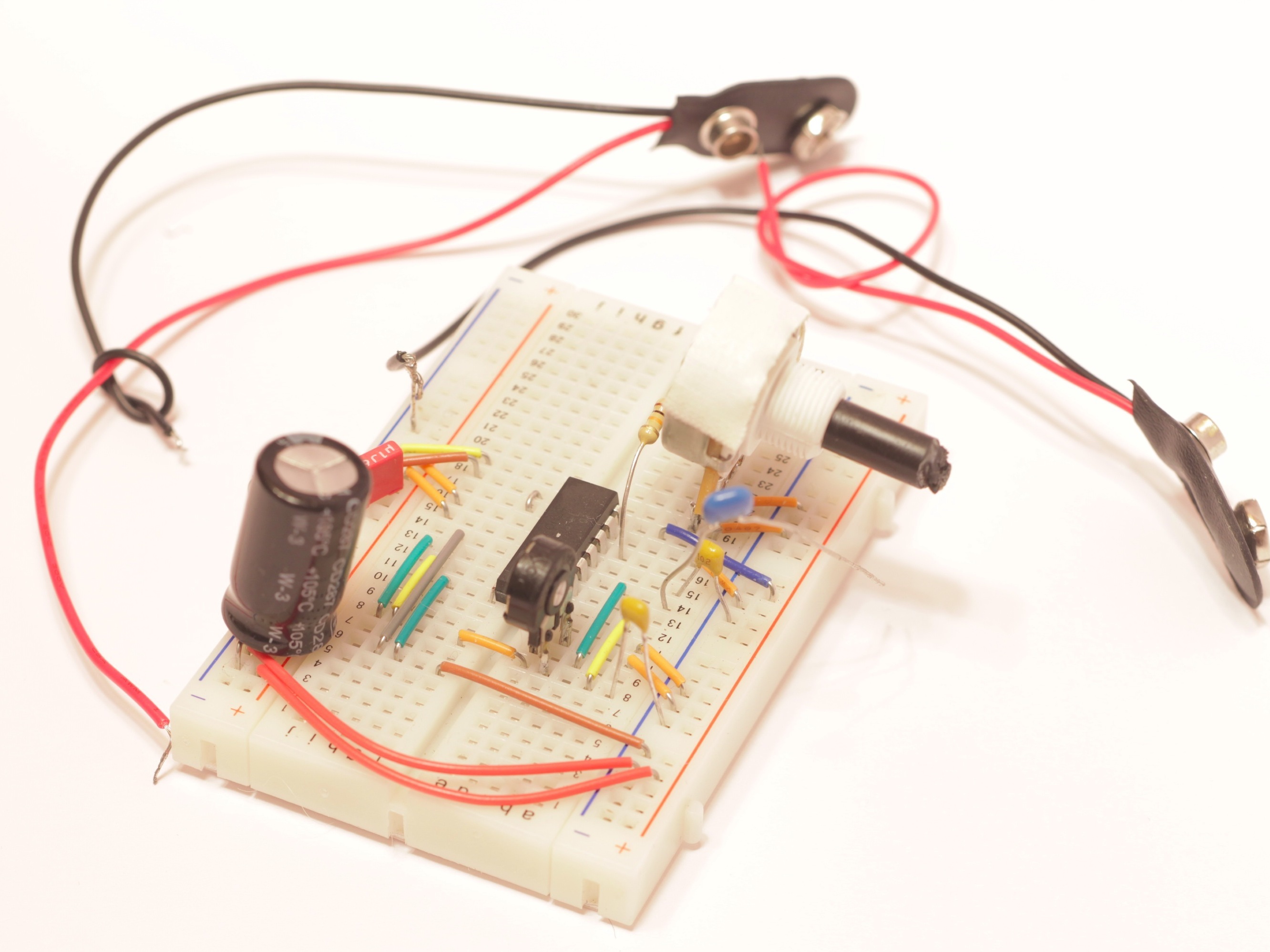

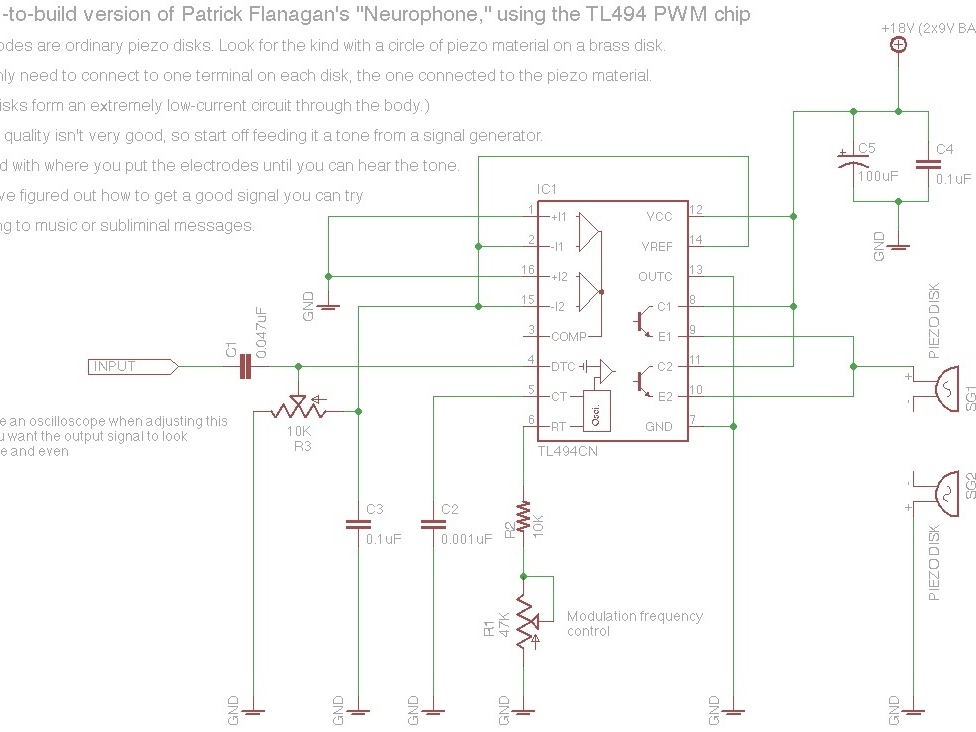

Fortunately, we don’t need to work with radio transmitters or high voltages. Over a decade later, Flanagan came up with a version of the “Neurophone” that didn’t use radio, or high voltages. (Patent US3647970)

The second version of the “Neurophone” used ultrasound instead. By modulating an ultrasonic signal with the audio we want to listen to, it gets picked up by a little-known part of the brain and turned into something that feels like sound.

The weird thing is this works even if the ultrasound transducers are far away from the head: maybe down at your waist, or even further (depending on your body).