If you need metal stuck together, there is no quicker path than buying a portable 110-volt wire-feed welder.

Being a snob, I used to scoff at these small welders as not being serious machines. Then I started seeing them everywhere — at every auto body shop and every metal gate installer; even hooked up to a generator at drag races.

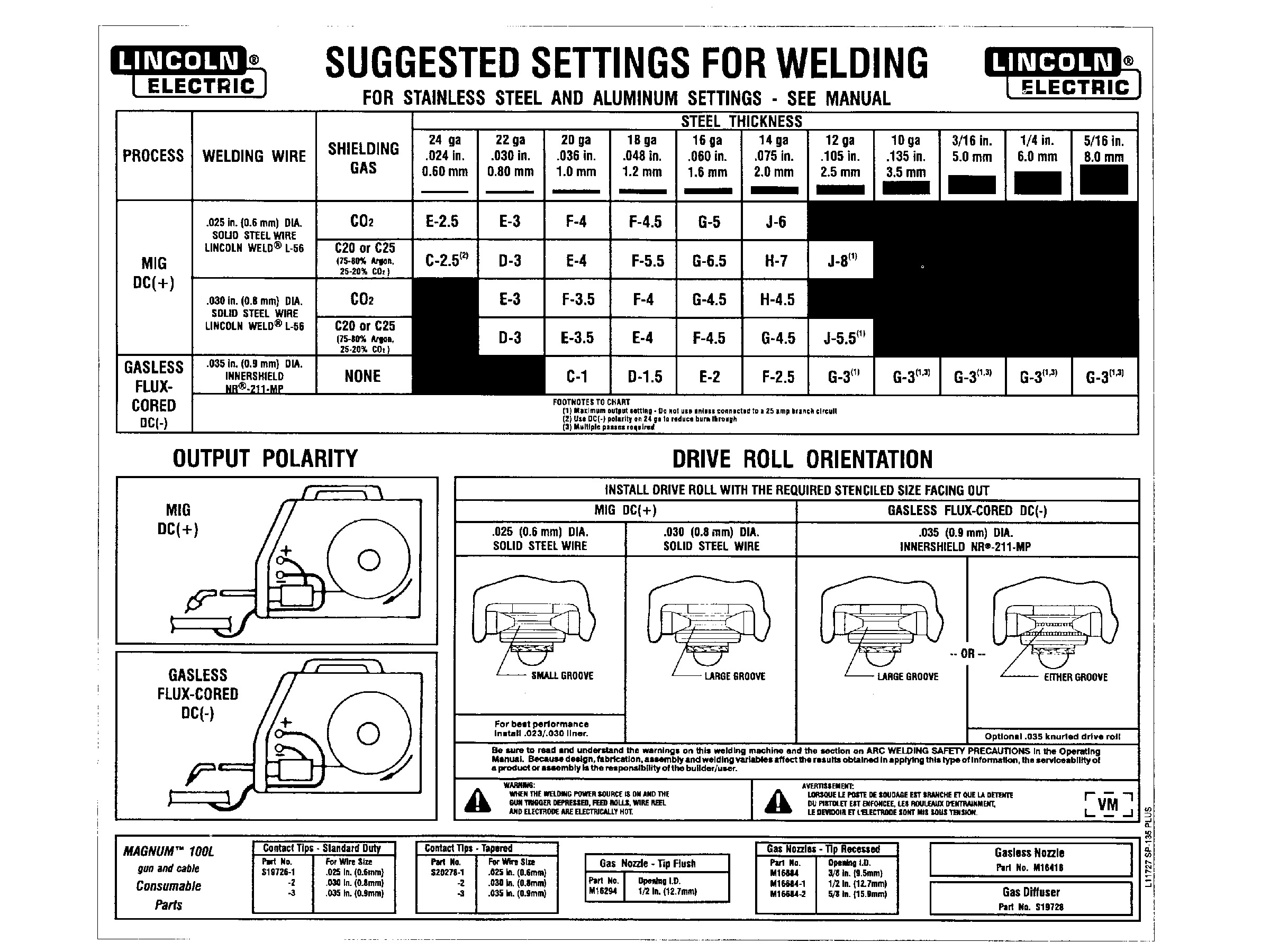

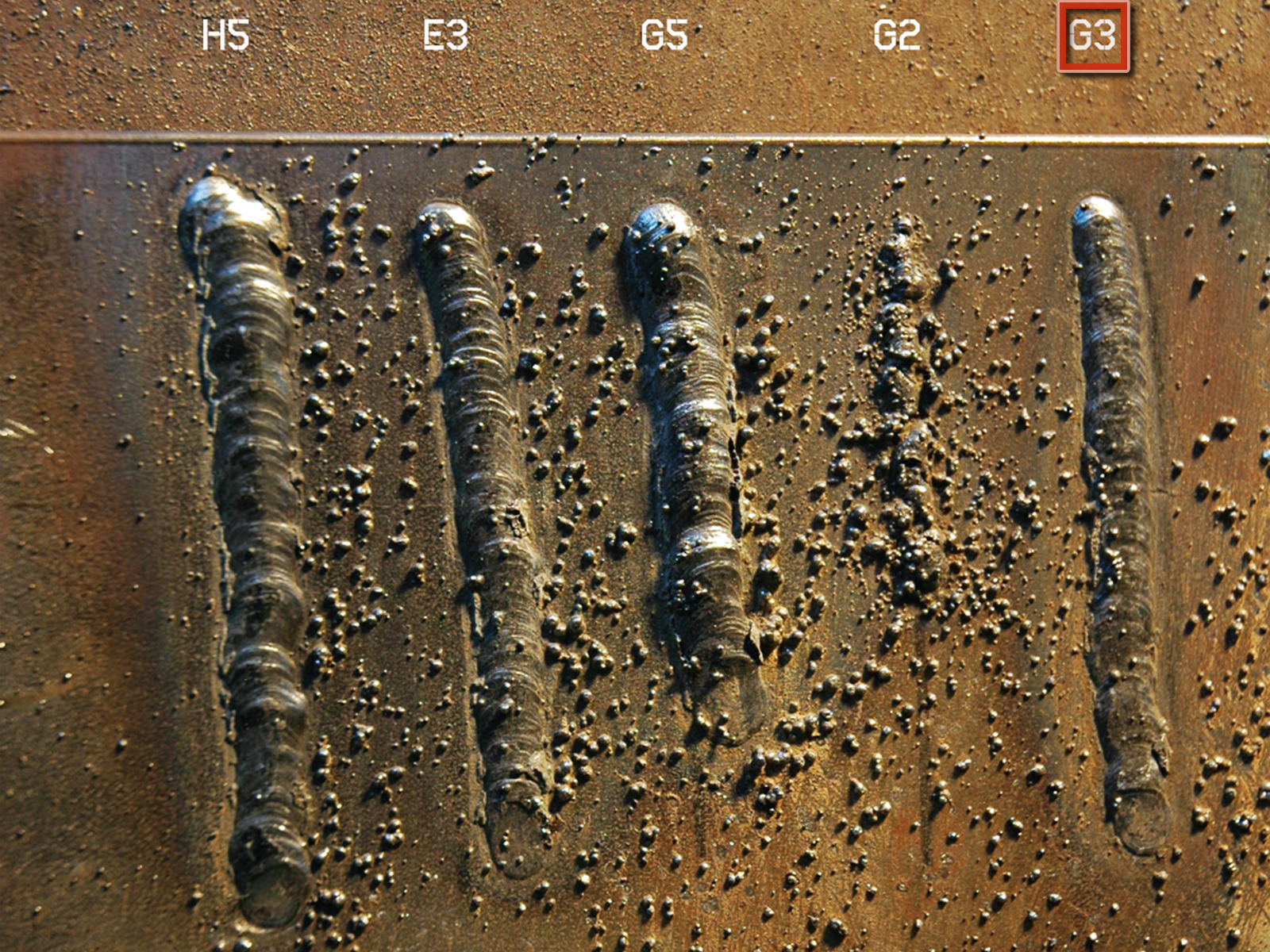

Having used a Lincoln 135 Plus wire-feed welder (about $600) for a month or two, I’m not scoffing any longer. Granted, it is not structural. You can’t weld a bridge, skyscraper, or engine mounts to a car frame. But you can weld steel up to 3/16ths, which is thick enough to make furniture, wrought iron gates, and bad art.

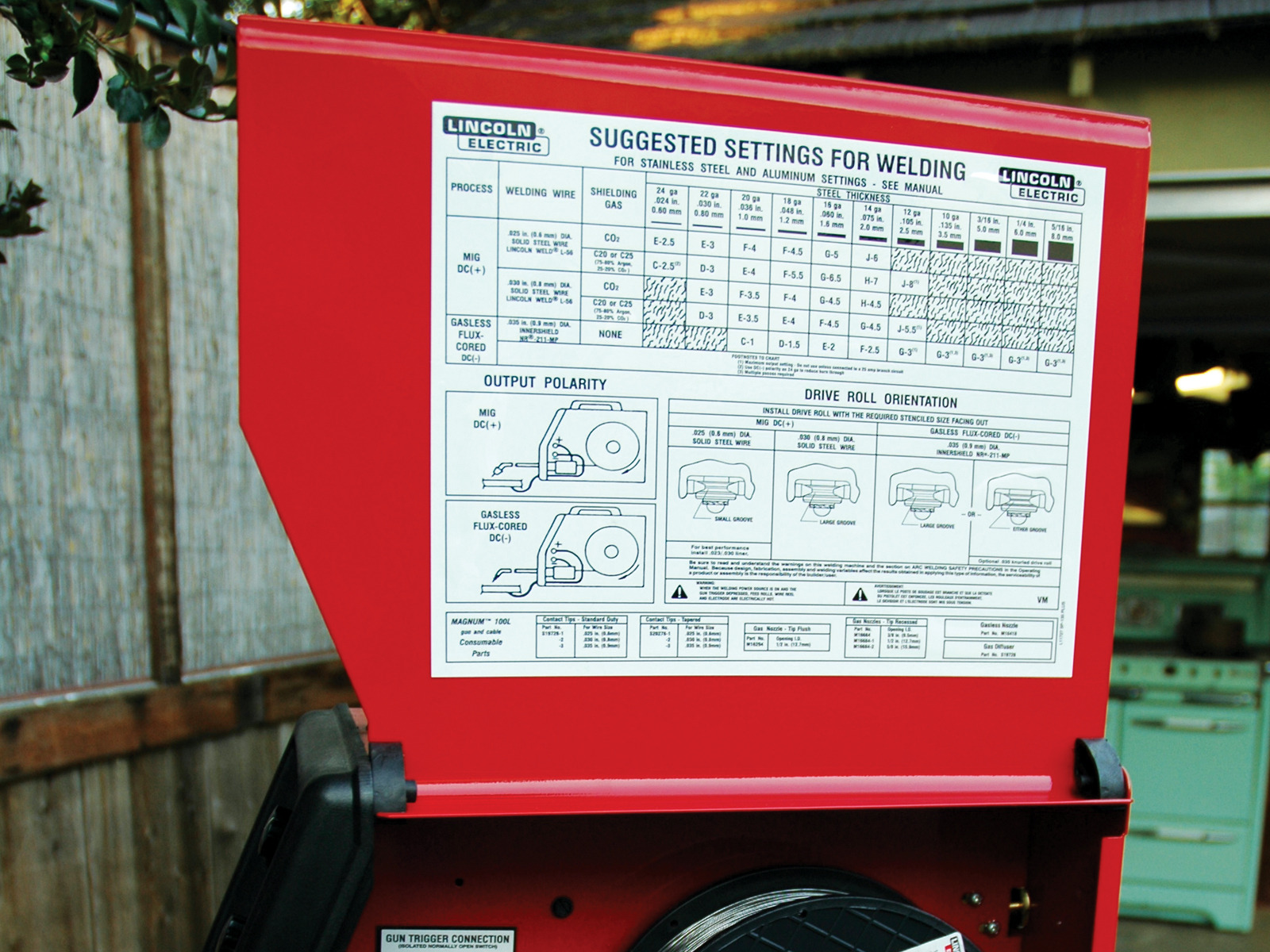

The beauty of the small Lincoln welders is they are light and portable. And when you get to wherever you’re going, you can plug them into a standard 110-volt 20-amp outlet. If you use the flux core kit, you don’t even have to carry around a tank of compressed shielding gas.

This article is not a replacement for the manual or the many excellent books devoted to welding. This is a primer to explain the process and show how you can be a welder by the end of the weekend.