Have you bought ink for your printer lately? If so, you probably felt a little annoyed with the manufacturer. For starters, there’s the horrendous cost — a full round of inkjet cartridges at Staples runs nearly half the cost of the printer itself. Printers are one of those famous loss-leader products like razors and kerosene lamps; you pay almost nothing for the gadget, then they gouge you on the supplies. Analysts estimate that the three big printer makers — Canon, HP, and Epson — make roughly two-thirds of their revenue from supplies.

But beyond the economics of ink, there’s also a lock on creative control. As long as the inkjet has existed, adventurous users have been able to peek under the hood, manipulate the driver software to create weird effects, manually tweak settings to eke out a higher quality, or even delve into the chemistry of ink itself. But that window’s closing. Since the inclusion of embedded microchips on ink cartridges, hacking these beige monsters is increasingly tough. A programmer needs to find the digital code on the cartridge in order to use bathtub ink and software, and that code is now harder than ever to access. Only 15% of users refill ink because of the hassles involved.

So it’s interesting to meet a professional inkjet printmaker who faces many of the same technical challenges but has to overcome them in order to stay in business. Someone like Jon Cone, 52, the inkjet pro behind art prints by artists such as David Bowie, Wolf Kahn, and Richard Avedon. The whole point of printing at the fine art level is to work with the artist to create a signature look.

Drawing on a degree in traditional printmaking from Ohio University’s College of Fine Arts, Cone works with artists to manipulate how the ink gets laid down on the page. Then he monkeys with the software to create subtle effects with the high-end paper his clients use — for instance, a recent job called for impossibly thick Japanese handmade paper, each sheet of which weighed 20 pounds and cost $5,000. “You can’t do a test run, you can’t see a preview in Photoshop,” says Cone. “After a while, you just get the feel of it and you start to think in ink.”

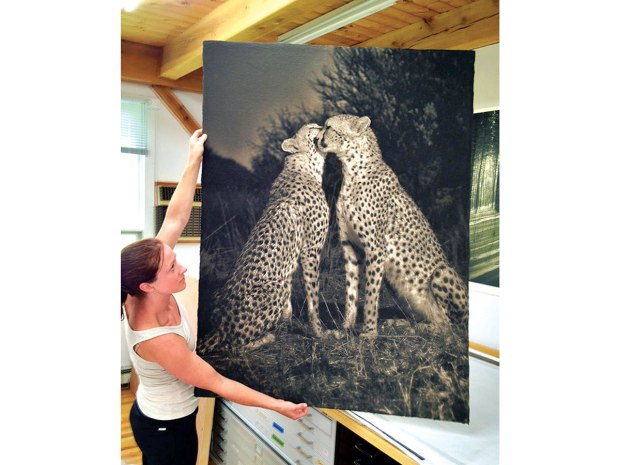

Cone’s workshop is in the middle of a 17-acre sheep farm deep in rural Vermont. It’s a little like a Bond villain’s hidden lair — remote, unassuming, and packed with high-tech gear. Inside the converted barn are a dozen wide-format printers perched on glossy hardwood floors. A $123,000 Iris machine spits out a print that will take several hours to finish. Meanwhile, Cone tinkers on a nearby Roland in preparation to handle photographer Zana Briski’s black-and-white work. Briski, the co-director of the Oscar-winning documentary Born into Brothels, wants rich images for this project with a palette tinted the color of tea and the images running over all the edges.

To create Briski’s images, Cone changed the firmware inside the device to think it had 12 inks instead of its standard six. To hold the new cartridges in place, he used steel washers and a custom jig he machined on the farm. He even designed the ink itself, had it tested for longevity, and then produced it with a Taiwanese partner (Cone runs a side business selling inks for high-end and consumer inkjets). The 12 different inks will give the image a full range of various levels of gray (a consumer inkjet typically creates gray with one black cartridge). Says Cone, “She wants tons of depth and structure, but if we use too much ink in any one spot it will bleed everywhere.”

Cone also printed the images for Greg Colbert’s “Ashes and Snow” exhibit, one of the most visited art exhibits in history. Colbert began showing his work on giant Polaroids, but needed a new method once the worldwide supply of 40″×80″ Polaroid film ran out. For two years, Cone designed inks, wrote printer driver software, and experimented with various papers to reproduce the otherworldly colors from the Polaroid process. Artists depend on such heroics because it lets them take an active role in the production of the art.

“When you buy any art print,” explains Charles James, a digital printmaker for BowHaus in Los Angeles, “You’re looking for evidence of the artist’s hand. A collector of Ansel Adams silver gelatin prints wants to know he himself did the dodging and burning and the developing. With digital, you’re looking for the same decisions, not what they did in Photoshop but the way they blended the ink and laid down the image on the page.”

“Because high-end printers only ship with automatic control, every print can look the same as every other print,” grouses James. “But there are people out there who want to push their printer to the limit. I don’t understand why the manufacturers haven’t embraced this.”

To keep their creative experiments going, Cone and other printmakers are in a constant cat-and-mouse game with manufacturers. Getting a printer to spit out specialty inks involves creating a software driver that makes the printer think it’s using a standard ink tank. But you need the codes inside the cart’s microchip to perform this sleight of hand, and sometimes it’s not that easy. With a sweep of his hand, Cone gestures to show how he is getting rid of the fleet of newish wide-format Epson printers in his shop, replacing them with Canons. Epson’s latest machines are too hard to hack, and he wants to standardize on a more easily modified platform.

For the technically minded consumer, Cone and others recommend keeping an eye out for well-made vintage printers in junk shops and on eBay. You might even find a few of Cone’s castoffs. “Save your old printers,” says Roy Harrington, who codes and sells a driver called QuadTone RIP. “Creativity is more than just hitting the Print button. The older equipment lets you get your hands into their machine and make your image just the way you want it.”

ADVERTISEMENT