It’s easy to hear about a cool sensor and decide to do a project with it.

“Oh, there’s a really neat X sensor that just came out. I should obviously do an X project!”

But this leads to an interaction that’s designed around the technology rather than technology that’s designed around a particular interaction.

When working with sensors, a good place to start is to think about what you’re trying to sense. What is the motion, action, or condition? What is the context and environment? What are the important aspects to consider? Then you can ask questions like these:

- “What different sensor (or sensors) could I use?”

- “What do I want to measure?” (sound, light, pressure, presence, etc.)

- “Where should the sensors live?”

- “What should I be looking for in the data I am gathering from them?”

In the following excerpt from the Sensors chapter of Make: Wearable Electronics, you’ll look at some possibilities for what to sense and a starting selection of sensors that will fit the bill. But keep in mind that this is just the tip of the iceberg. Once you have a project idea in mind, you should go out and research what’s available to best help your idea come to life.

Flex

Bodies are bendy and it just so happens that flex sensors sense a flex or a bend. They’re very good for areas of the body that bend in a broad, round arc. They work well on elbows, knees, fingers, and wrists. They are variable resistors and need to be used in combination with a voltage divider circuit in order to be read by a microcontroller.

The biggest challenges in working with flex sensors are positioning and protection. In order to get an accurate reading of the flex of your elbow, the sensor needs to be positioned in the same place on your elbow every time. Creating a secure pocket for the sensor can help with this.

The other thing to consider is that while flexing is a pretty rigorous and strenuous activity, many flex systems are fairly delicate, particularly at their connection terminals. Be sure to protect your connections. Reinforce with heat-shrink, and protect them with some sort of material.

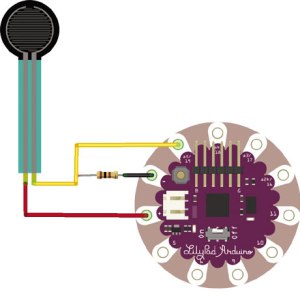

Force

Bodies often touch and get touched. One way to sense touch is through the use of force-sensing resistors (FSRs). FSRs have a makeup that’s similar to flex sensors but are configured to be sensitive to pressure rather than bending. They are also variable resistors and have delicate connections similar to flex sensors.

Stretch

From the bend of a knee to the expansion and contraction of a rib cage with each breath, properly positioned stretch sensors can capture the fluctuating nuances and curves of the human form. A stretch sensor is simply a conductive rubber cord whose resistance decreases the more it gets stretched. This is yet another example of a variable resistor.

Stretch sensors come precut at different lengths with hooks crimped to either end for easy connection, or you can buy it by the meter and cut it to whatever length you need .

Stretch sensors are a fun material to work with. They can also be elegantly incorporated into textiles through knitting or weaving.

Movement, Orientation, and Location

People are active and mobile creatures. They reach for things they want, turn toward loud noises, and crouch down to coax the cat from under the bed. When creating wearables that react to events such as these, it is helpful to be able to sense movement.

A cheap and easy way to sense movement is through the use of tilt switches .

But there are also far more sophisticated sensors that you can use. Accelerometers measure acceleration or changes in speed of movement. They can also provide a good measurement of tilt due to the changing relationship to gravity.

Accelerometers have a set number of axes — directions in which they can measure. The ones shown above are three-axis accelerometers, meaning they can measure acceleration on the X, Y, and Z plane.

If tilt, motion, and orientation aren’t enough, and you want your wearable to know where you are on the planet, GPS is the way to go. Just like your car, bike, or phone, your jacket or disco pants can have GPS, too. There are a number of Arduino-compatible GPS units available, but the Flora GPS is a compact and sewable option.

Heart Rate and Beyond

Your heart beats faster when you’re excited, and your skin gets clammy when you’re nervous. Besides sensing your environment and your movements, you can also use sensors to learn more about what is happening within someone’s body. A great place to start sensing these biometrics is pulse or heart rate.

Optical heart rate-sensors, such as the Pulse Sensor Amped, are a small, lower-cost solution for measuring pulse. This type of sensor measures the mechanical flow of blood, usually in a finger or earlobe. It contains an LED that shines light into the capillary tissue and a light sensor that reads what is reflected back. It produces varying analog voltage that can be read by the analog input on any Arduino.

Chest-strap heart monitors are a more expensive but more accurate solution for measuring heart rate. They measure the actual electrical frequency of the heart through two conductive electrodes (oftentimes made of conductive fabric) that must be pressed firmly against the skin. Polar produces heart rate monitors that wirelessly transmit a signal with every heartbeat.

Proximity

Sometimes you will want to know how close or far away something is from the body. Proximity sensors are useful for detecting nearby objects, walls, or even other people. When selecting a proximity sensor, it is worth considering what your desired range or detecting distance is, as well as what sort of beam width you need to monitor.

Light

The most basic type of light sensor is the photocell. Its resistance varies based on the level of light it senses. Some have resistance that increases as the light level increases, but some have the reverse relationship. This can be quickly determined by viewing the sensor values in the serial monitor.

The photocell is a great sensor to work with because it is small, easy to manipulate, and incredibly inexpensive. It can be used to sense ambient light levels, but it can also be used for less intuitive purposes like determining whether a jacket is open or closed or if the heel of a shoe is on the ground or in the air.

ADVERTISEMENT