Among MAKE readers, we’re nearly unanimous in agreeing that the rise of digital fabrication is a complete game-changer for crafters, hackers, and tinkerers of all stripes. Laser cutters, CNC mills, and 3D printers have altered the way we think about design, and raised the bar for quality and precision in our work. I’m a passionate adopter of these technologies, but am also wary of the cultural shift they represent as they become more ubiquitous.

I was talking to a friend about this recently, voicing my disappointment in so many talented colleagues of ours who stay strictly within software, afraid to pick up tools with which they could alternatively realize their creations. His response surprised me: “I’m more comfortable with a Wacom and Photoshop. I grew up with computers and I can’t imagine creating with anything else. I think digital fabrication is the future and I want to be a part of it.”

What are the dangers in relying only on digital fabrication? What are its limitations? It’s certainly another powerful tool in the toolbox, but then something that’s laser cut or 3d printed has a certain type of look (industry shorthand to this effect has already developed amongst design firms.) Also, technologies like this are still expensive and can’t be easily used “on the job”. For example, you can make an enclosure for your Arduino project, but I challenge you to rapid prototype an entire house. I’m not a Luddite, but there’s something seemingly dangerous in not learning basic manual craftsmanship. Working with materials physically awakens certain creative techniques that can’t exist with a Wacom and stylus. The comparison is almost one of analog versus digital.

Digital fabrication relies on discrete iterations. It’s made or it’s not made, it’s changed or it’s not changed. Program the machine, wait for the prototype to come out. You don’t like it? Throw it away and start again. Desgning something with digifab from start to finish without touching a standard tool to it is certainly possible but this isn’t true in every case. Part of the danger in this assumption is in the need for further assemblage. My friend may have the CAD skills to design something like Makerbot’s turtle shell racer, but he’d still need the knowledge to put those parts together into a cohesive product once they’re printed.

Compare this to a wood bowl you’re turning on a lathe. You control the exact amount of pressure and time that you press your chisel to it. You even choose the chisel and you sharpen it yourself. How the grain of the wood responds to your touch informs your design decisions in real time. It’s a more intimate interaction, and informs the final product.

On the other hand, being a bit of a wood butcher myself, I know it takes hours and hours, years even, of practice to make products by hand that also look professional. Did I do myself a disservice by spending so much time with drills and saws, and not enough with Rhino and Illustrator? Woodworker and designer Ben Light says, “The old and new can live together quite beautifully. Skill, technique, and craftsmanship will always rise to the top whether it be digital or analog, but a comfort level or proficiency in one area shouldn’t scare you off of the other.”

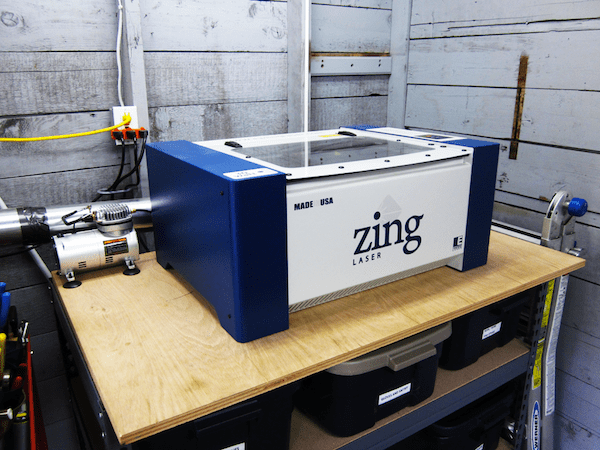

Should we forge ahead with our Makerbots and Zings, never looking back? Or should we stick with old reliable tools, lest we become too advanced and lose our way in light of some catastrophe, like the ancient Minoans or users of the Template Construct in Warhammer 40000? I’m hedging myself and will remain pleased with a mix of both, but I’m more curious about what you think. Let’s hear it in the comments.

More:

ADVERTISEMENT