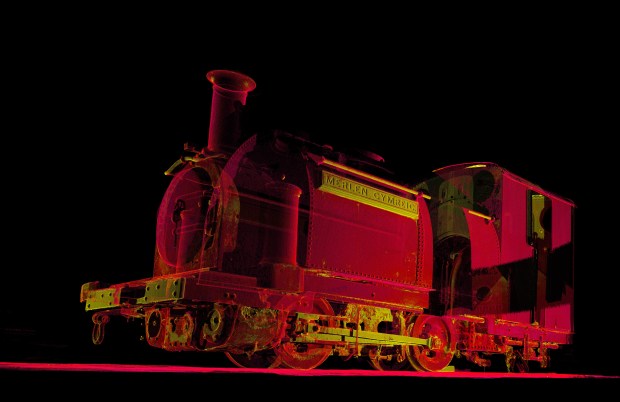

The mainstream news media is awash with speculation that 3D printing is bringing about a second industrial revolution. Whether this is true or not, nowhere is the comparison more apt than with The Flexiscale Company, a small UK startup making 3D models of the great steam engines of the first industrial revolution.

I caught up with Flexiscale‘s Chris Thorpe, for my podcast, Looking Sideways, and he filled me in on how they’re testing new ways of manufacturing, how they laser scan an entire locomotive, and what we can learn from the Victorians about making, modifying and improving the stuff around us.

Flexiscale identify interesting and historic steam trains, wagons and other stock, scan them to make 3D point clouds, and turn those scans into 3D models. Then they’re broken out onto sprues for model railway enthusiasts to make at home.

For Chris, it comes from a deep affection for model-making that started in his childhood:

“I’ve made models of trains for a long while and it’s frustrated me that you have really work quite hard to make kits. I grew up making Airfix kits, and there’s something lovely about making one. They’re very simple, but they’re very malleable as well. You can convert them into other things, either real things or imaginary things. The majority of kits you get nowadays for unusual trains are these really hard to make etched brass kits, which I always describe as origami with jeopardy. You get a flat sheet of brass that’s been photo-etched, which you have to then turn into this three-dimensional shape. You fold it, and file it, and solder or super-glue it. And normally, at some point I end up super-glueing myself to it, or or burning my fingers while soldering.

“If you look at the mass market, everyone makes a model of the Flying Scotsman, or Mallard, or one of these big engines. But there’s a large segment of the market that doesn’t want a model of the Flying Scotsman, or if they do want it, they actually want to make it themselves, rather than have a finished item.

“The things that you buy from the big manufacturers are almost too perfect. They’re too finished, and there’s no craft in them. The only craft you can do is to take them out of the box without breaking them; that’s your only interaction with them. And as a result, the only story you can tell about them is of their purchase, rather than the pride of ‘I made this’ or ‘I improved it’, or ‘I put these extra detailing parts on’.

“There seems to be this schism between the perfect readymade, and the really hard-to-make obscure things, and we want to sit in the middle, making the obscure things easier to make.”

How it works

What enables Flexiscale to fill this gap is a perfect set of technologies that have only become aligned in the last few years, in particular: crowd-funding for investment, laser-scanning to capture the detail of the trains, and 3D printing, to allow them to manufacture small quantities of the finished models.

It starts with a community of enthusiasts, coming together to propose — and invest — in new models of the engines and rolling stock they love:

“One of the first things we set up was an organisation to crowd-source models,” says Chris. “People can come to the website and submit a project to us, we then open it up to the public to vote on, and when we get to a critical mass, we approach the museum who’s got one of these and say, can we come and measure and photograph it, and produce a kit.

“On the slightly more complicated side — and by that I mean a whole steam engine — again, we talk to the railway, we run a Kickstarter campaign to get the funding for it, and when the funding comes through, we go and laser-scan it.

The scanning is carried out by Digital Surveys, a company that specialises in oil rigs and petrochemical plants — installations with a lot of pipework, in other words. The 3D data is then cleaned up and turned into a 3D model by Vijay Paul AKA DotSan on Shapeways, and then printed on-demand by PD models

Only producing the things that people want

As well as allowing Flexiscale to print complex parts that wouldn’t be possible with more traditional injection-moulding techniques, 3D printing lets them to test out how new manufacturing techniques work, and whether they can help solve some bigger problems.

“I’ve been increasingly perturbed by injection moulding over the years,” says Chris. “Lots of stuff is produced but isn’t necessarily ever sold, and goes straight to landfill. It’s cost-effective to do 1000, out of a mould; it’s not very cost-effective to do 100 or 10. And so, as a result, people do 1000, and then they sit in warehouses.

“Whereas we only actually print when somebody orders a kit, and so it allows us to do just-in-time supply chain.

Physical pull requests

Crowd-funding, laser scanning, 3D printing: these feel like very modern ideas. We might imagine a Victorian engineer being amazed by the world as we see it today. But in the process of delving into the past, Chris has discovered that the engineers of 150 years ago were already using working practices that we consider inventions of our time.

“Whilst we’ve been doing this work on Victorian steam engines, we’ve been discovering some really interesting things about the industrial revolution and the era after it — the era between railways starting and mass manufacturing being off-shored to China, and so on”, says Chris.

“What you start to see is collaboration between suppliers — the locomotive manufacturers — and the users. It’s the sort of collaboration you see in large software projects.

“Because these things had such a long lifespan, they were constantly being evolved. Particular engines were in the catalogue for 60 or 70 years. Over time they mutated, they took on lots of the modifications that were coming out of use in the field.

“I realised that it looked like pull requests in software libraries. If you look at the UK government project that launched last year, gov.uk, one of the most amazing things about it is that all of us armchair developers can get at the source code. We can make changes and submit them back, and if they’re suitable, they get rolled into the codebase and then shipped out on the website.

“If you look at lots of these steam engines, you can see almost the evidence of physical pull requests. They’d make a change in the field, and then they’d go back to the factory and the people who were doing the large overhauls would look at them and go, ‘ah, that’s really clever, we should do that’, and then they’d incorporate that in the design going forward.

“They’re co-designing the next set of locomotives to suit their needs better. We see co-creation and open innovation as being enabled by the digital world, but actually I think it’s more enabled by having a connection between consumers and manufacturers — the actual people who make the things.

“When we off-shored lots of the manufacturing, what we lost was a confidence as well as an opportunity. Over time, we lost the knowledge of how these things were made, and we lost the confidence that we as a country could engineer these things, we could fix them, change them, we could demand more out of them.”

Listen to the show to hear how Flexiscale are working with train restorers to make 1:1 models, the dilemmas of restoration and the preservation of craft skills, and why the future might be in selling shapes, rather than plastic.

Andrew Sleigh is a writer, researcher and maker, with an interest in maker entrepreneurs. He’s setting up a hardware startup group in Brighton, UK, and he also helps run Brighton Mini Maker Faire, now in it’s 3rd year.

ADVERTISEMENT