As part of our coverage of 3D printing, laser-cutting, CNC routing, and other forms of desktop fabbing — to coincide with the new “Your Desktop Factory” issue of MAKE — we’re thrilled to welcome guest contributor Shawn Wallace. Shawn is a member of AS220, the Providence, Rhode Island community arts space. From there, he weekly plugs into the global, distributed learning collaborative known as the Fab Academy. In a series of the “Letters from the Fab Academy,” he’ll be sharing with you what the group is up to. Welcome Shawn, and all the members of the Fab Academy! – Gareth

Make a Press-fit Construction Kit

Since October of 2009, a handful of small groups of students have been taking part in an educational experiment called the Fab Academy. The Fab Academy is a distance learning collaborative that’s built on the infrastructure of the Fab Lab network. Labs in Spain, Iceland, Kenya, Amsterdam, India, and Rhode Island participate in Wednesday morning lectures by videoconference. The curriculum is concentrated into two week topics with a project due at the end of each and a more ambitious annual project due at the end of the year. This series of articles for the Make: Online will follow each of the two week sessions in the curriculum and highlight the work, tools, and techniques being developed in the pilot year of the Fab Academy.

All Fab Labs are equipped with a laser cutter for cutting non-metallic sheet material up to a quarter inch or so, as well as a vinyl cutter for cutting adhesive films for signs, flexible circuitry, and antennas. The first Fab Academy section focused on techniques of computer-controlled cutting. For background on specific brands, accessories, and software, check the frequently-updated inventory of Fab Lab tools at the Center for Bits and Atoms site.

The goal of the first assignment — make a press-fit construction kit — was to get a feeling for settings, materials, and the workflow of creating files for the tools. Press-fit construction is a way of building things without adhesives or fasteners; parts are designed to be held tightly together by friction, but not so tightly that they can’t be pulled apart with a stiff tug. Applications can range from flat-pack style furnishings, like Elliot Clapp’s slideholder lampshade (below), to Larry Sass’s human-scale prefab New Orleans house.

In press-fit construction, the fasteners are integral to the piece. This can be a big win because regular hardware fasteners can add up in numbers and cost very quickly. For materials, cardboard and birch plywood are the old standbys. Acrylic is usually too brittle (except when it isn’t). Delrin is a terrific, strong, and flexible plastic, but it’s slippery. Makeda Stephenson changed the frequency of the laser cutter to perforate all the cuts and create little teeth in her Delrin construction set, as seen below.

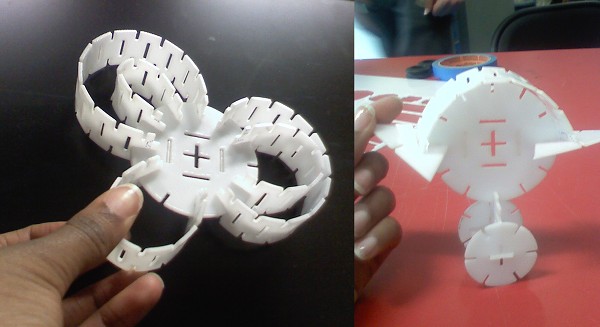

Paper is also a nice material to work with:

Fairly precise cuts are necessary in press-fit construction, in the thousandth-of-inch range. Although the laser cutter is a very precise tool, you’ll still find a measurable variance in kerf (i.e. width of material removed) depending on the material, the state of the optics, and the quality of the air exhaust. You’ll also find that off-the-shelf sheet material like plywood usually varies from piece-to-piece by +/- .005 inches or so.

Because you will inevitably have to tweak a press-fit design to match the materials and equipment at hand, your design should be created so that the width of slots and notches can be changed parametrically. It’s also important to chamfer (i.e. cut at a 45 degree angle) the edges of the press-fit notches. Without a proper chamfer, you may not be able to slide the pieces together to get an effective joint.

Some sample joints (clockwise): low-profile slider with wedge,

flush with wedge, push-through with clip, simple notch and slot

One of the tenets of the Fab Lab network is that designers should be able to transcend any particular tool, particularly proprietary tools. At the Providence Fab Lab, we use all open source software for our basic lab infrastructure (although people are certainly free to use whatever tool they want). We print to the laser and vinyl cutters using a custom open source driver for the Common Unix Printing System (CUPS), written by Brandon Edens. This software allows us to eschew the usual proprietary Epilog/Corel Draw workflow found in most laser shops. Almost everything in the Fab Lab can be created within Inkscape and QCad, or by writing simple programs using the cad.py Python script.

Inkscape is a great open source vector drawing program. When designing for the laser cutter, thin red lines cut and black/grey values are engraved. Note the chamfers…

Full-featured CAD programs, like QCad, make it relatively easy to parameterize parts, but it’s also possible to use Inkscape to make parametric designs using the clone tool. First, follow these steps to determine the base size of a press-fit notch:

- With calipers, measure the kerf created by your laser cutter. (You do have a laser cutter, don’t you?) Cut a square, then measure the inner dimension of the hole and the outer dimension of the piece. Subtract and divide by two: this is the kerf for that material.

- Measure the thickness of the material, preferably with calipers.

- Use these measurements to draw your best guess for a notch

- Duplicate the notch a few times and bracket in .001 inch increments (i.e., make some at w-.002″, w-.001″, w+.001″, w+.002″ etc.).

- Cut and test the fit

Once you have a good dimension, create a template layer in Inkscape with your basic notch shapes. When adding a notch to your design, use the Edit->Clone option to create a linked copy of the notch. When faced with modifying your drawing for a new material width, update the dimensions of the notch in the template layer and watch those changes update throughout the document.

Here are a few last examples of work from the class:

A fabulous flex-fit rotating joint by Benito Juarez of the Barcelona Fab Lab.

Press-fit models from Victor Freundt in Barcelona and Gísli Matthías Sigmarsson in Iceland.

Press-fit linear bearings in Jonathan Ward’s MTM A-Z milling machine (demoed by Noah Bedford, left) and a press-fit pinch roller from the Fluxamacutter DIY vinyl cutter (right).

In my next article, we’ll discuss electronics design and production, the Fab Lab way.

From MAKE magazine:

MAKE Volume 21 is the Desktop Manufacturing issue, with how-to articles on making three-dimensional parts using inexpensive computer-controlled manufacturing equipment. Both additive (RepRap, CandyFab) and subtractive (Lumenlab Micro CNC) systems are covered. Also in this issue: instructions for making a cigar box guitar, building your own CNC for under $800, running a mini electric bike with a cordless drill, making a magic photo cube, and tons more. If you’re a subscriber, you may have your issue in hand already, and can access the Digital Edition. Otherwise, you can pick up MAKE 21 in the Maker Shed or look for it on newsstands near you!

2 thoughts on “Letters from the Fab Academy, Part 1”

Comments are closed.

ADVERTISEMENT

Join Make: Community Today

Welcome, Shawn! This stuff you all are working on sounds amazing. I can’t wait to read your future letters.