NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena is a small city of sleek, modern towers propped tight between the San Gabriel Mountains and the dry arroyo landscape of Southern California. Inside, the smartest minds on the planet gather daily to design, build, and launch rockets, satellites, and rovers to explore space and faraway worlds.

My visit here in mid-May is to get a sneak peek at one of the newest rovers, launching for Mars in 2020. It’s a flagship mission, announced in December 2012, a few months after the landing of Curiosity, and will feature a similar but slightly larger six-wheeled craft. JPL, however, doesn’t have a high-tech prototype. Instead, they lead me into a demonstration room, have me put on a Microsoft HoloLens headset, and boot up a CAD projection of the rover. It appears in full scale and fully explorable right in front of me, while they explain that this virtual approach to engineering is not a future part of their organization — it’s happening now.

(Listen to our interview with JPL’s Dr. Jeff Norris here)

BUILDING VIRTUAL ROVERS

JPL terms this mixed reality, a relative to virtual reality and augmented reality. “The manifestations that we’re creating feel like real objects that interact with the world in the same way that real objects do,” explains Jeff Norris, the head of JPL’s Mission Operations Innovation Lab, differentiating his output from the full immersion of VR and the heads-up-display overlay he associates with AR. And even though it’s clearly just a multicolored CAD rendering visible through a postcard-sized viewing area in my headset, the mixed-reality projection of the Mars 2020 rover is quickly convincing.

The program, called ProtoSpace, perfectly tracks my movement around the rover, letting me peek up top or kneel down to inspect the underside, while seeing my actual surroundings as well. My brain buys in so much that at multiple times I reach for my camera before remembering nothing is actually there. After a point, I’m directed to put my head through the rover itself. It is momentarily challenging to get my body to agree, but as I do, I watch the components peel away layer by layer, until I am in the hollow center of the vehicle.

“I think a tool like ProtoSpace allows us to access the same intuition that we have when we’re stacking up a bunch of blocks, but we’re working with far more sophisticated blocks and much more challenging goals,” Norris says. It’s already shown its worth on at least one project, an Earth-science satellite that was designed with tight clearance for assembly. Upon examination in ProtoSpace, one of the technicians realized it would be too narrow for the tooling to fit inside. So they redesigned it long before a single physical part was built, saving time and resources.

“The field is moving so quickly right now that I feel like it’s totally different from where it was a year and a half ago,” Norris says about the technology used. And they’re still expanding ProtoSpace, planning new features such as the ability to pull individual pieces off of a model for inspection, add animation and movement, and eventually even create designs in the mixed-reality environment itself.

WALKING ON MARS

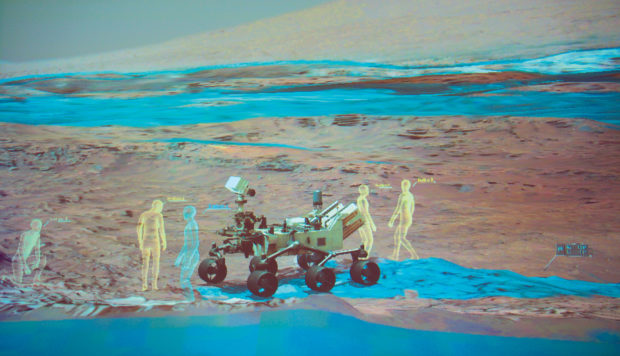

In the next room, Norris and his team show off their other mixed-reality project: OnSight, a virtual visit to the surface of Mars using images collected by Curiosity. It’s similarly believable, with a photo-realistic Curiosity in the center of the room, but this time the planet’s terrain extends outward to the horizon as you look up and turn around.

Mars data scientist Fred Calef shows me the details of the rocky outcroppings as I step around. He’s physically in a different part of the building, but I see him as a glowing blue avatar next to me on the planet. This is a big advantage of these two projects, the ability to interact with colleagues who aren’t actually with you. JPL engineers can easily beam together with scientists on the other side of the world to examine and discuss a spaceship design, or determine the next destination a rover on another planet should head to.

A few minutes later Calef comes into the room. I ask if, when Curiosity successfully touched down on Mars in 2012 he had any idea that four years later, he’d be standing next to the rover on Mars itself. He shakes his head no. “It really snuck up on us.”

And he’s glad it did, because it makes his job easier. “It’s really about saving time as much as we can,” he says. “Because time is science.”

PUBLIC CONSUMPTION?

NASA is opening a Destination: Mars experience at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to let visitors have the same HoloLens Martian visit, guided by a holographic Buzz Aldrin. After that, Norris is excited about more community access, eventually seeing ProtoSpace and OnSight coming into your home. “If you can imagine a future mission on Mars where we have millions, even a billion people, exploring right alongside with the vehicle — and maybe someday with humans — from their living rooms with headsets on their heads, I think that’s a great way to share this,” he says.

And it’s not just for sightseeing, but also for new ways of designing and building, for everyone. Norris continues, “My hope is that tools like ProtoSpace and mixed reality in general can unlock a whole new sophistication … not just for professionals, but for amateurs … people who are just enthusiastic about making things.”

ADVERTISEMENT