I grew up without electricity, Wi-Fi, or running water. I lost my mom at 16. I wasn’t afforded a traditional education. But, now 19, I’ve been able to build amazing things with other young people — some from poverty, some from privilege — who’ve come together to prove that what matters most is community. I got into tech by necessity. The world is full of technical problems, and even the “small” ones are very real to those experiencing them. It was hot where we lived in Nassau, The Bahamas, and we needed a fan for my grandmother. The lack of electricity was a problem. So I went to the library to do some research, and realized I could use a small solar panel and an Arduino microcontroller to work a blade from an old fan I’d found. My chess teacher was kind enough to provide the money I needed, and soon the problem was solved. This taught me that I could sit in the heat and be miserable or I could go find a solution — and that when I did the work, people would often meet me on my way with helping hands.

When I was 17, I received a grant to attend a hackathon in San Francisco, run by a group called Hack Club. This is their story, my story, and the story of other teen Hack Clubbers and what we’re building together.

A Global Teen Hacker Club

Hack Club was founded in 2014 by teen programmer and high school dropout Zach Latta. Zach struggled in a public high school that didn’t offer a meaningful computer science program. He’d been looking for friends who also loved computers, and at 16 he decided to build a community for other young makers and leaders. His efforts won him a Thiel Fellowship and $100,000 to bring his vision to life — a place where bright, tech-curious young people could collaborate and build faster by building together. Zach was later joined by his co-founder, Christina Asquith, a journalist and war correspondent who’d founded The Fuller Project, a journalism nonprofit focused on issues affecting women and girls globally. Together, they set out to build Hack Club into a worldwide nonprofit program, inclusive of all teenagers regardless of gender or financial background, that will bring together hundreds of thousands of young people who love to build and make projects with technology, art, and creativity. It worked. I no longer have to code alone on my phone, and both my social network and comfort zone are much wider now. And it isn’t just me.

Riding the Wave

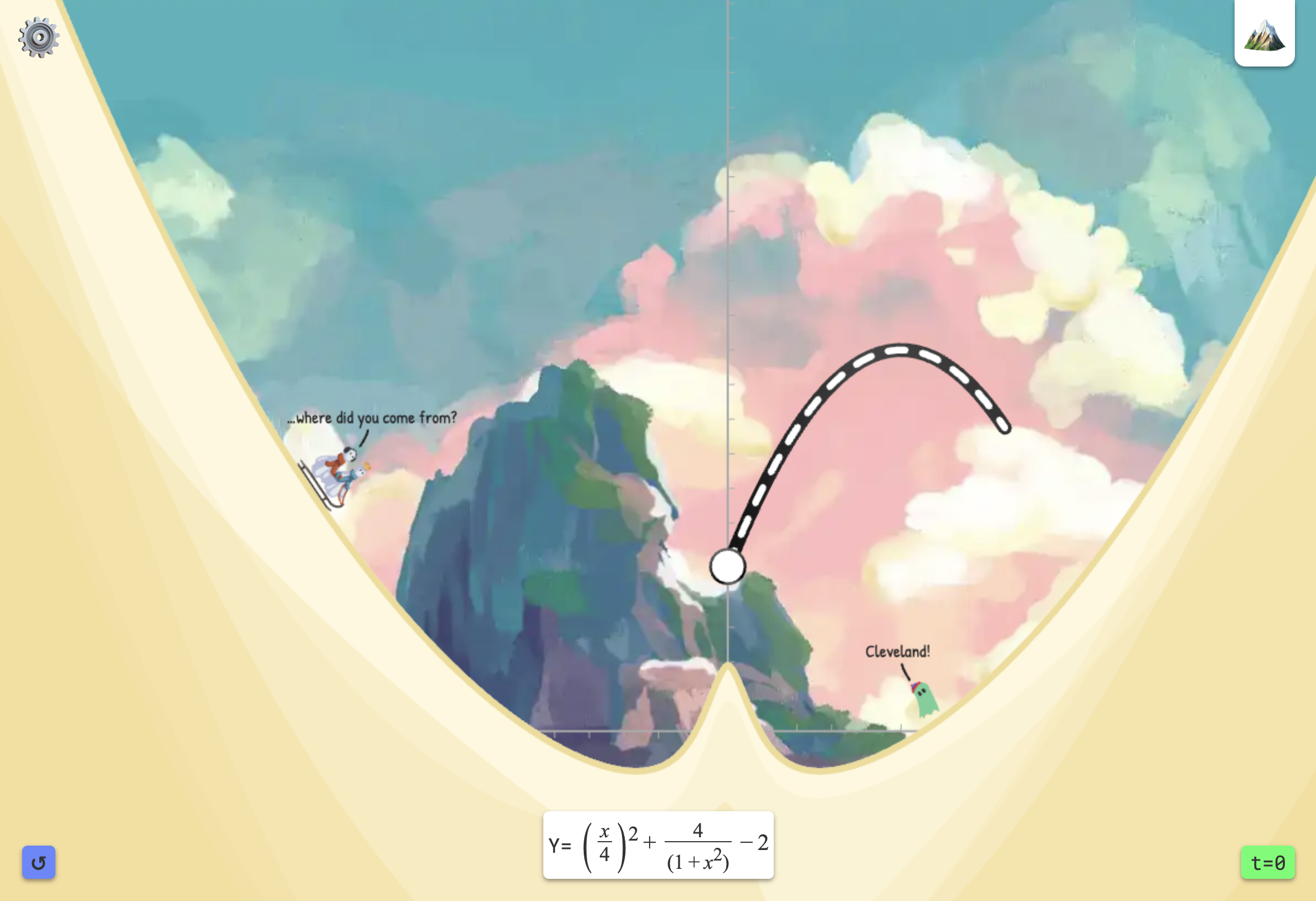

Chris Walker had a typical experience in high school math class: turning to playing on his TI-84 graphing calculator to cure his boredom. But this gave him an idea — making a game where ghosts would sled down graphs, backed by beautiful artwork, to make abstract math problems more engaging. Chris worked on SineRider for years, but was never able to get it over the finish line — until joining Hack Club, where a team of 20-plus teenagers across the globe then spent their evenings and weekends finishing his work. One of those contributing coders was Aileen Rivera. The pandemic era had been lonely for her, as it was for most students, whose social lives were suddenly upended. She had all the curiosity, but without the community, in her words, “I often just didn’t know how to fix issues or improve my projects. My school didn’t have any real resources, and I didn’t have anyone to ask. Now I’ve got best friends working alongside me … we can make progress together, share ideas, and just be less isolated.” SineRider’s appeal was obvious, she says. “The game was just very different, bringing art and actual fun to math. And what’s beautiful is that it’s built by young people for other young people.” Their efforts paid off. SineRider is played by thousands of students worldwide daily to improve their understanding of functions. And Aileen is working on its translation system so that students can play it in their own language. With Hack Club’s help, she has also launched her own hackathon in her native San Antonio, Texas — and is working on an AI education tool while teaching herself biomechatronics.

Make on a Train

“There’s no way this is actually happening. There’s no way a nonprofit is sending like 42 people around the country to make stuff on a train.” Ian Madden was in the eighth grade when he uttered the above, before beginning the Zephyr hackathon, a 3,502-mile train journey from Hack Club HQ in Vermont, through New York City, Chicago, and the Rocky Mountains en route to Los Angeles, California. One of his first projects was fixing an out-of-control database issue with the ticketing and scrapbooking tools for a big hackathon — while at the airport on his way to attend, which taught him as much about the technical side as the logistical. Hence most of Ian’s work since: helping to build out the unique infrastructure that’s powering both the club’s in-person events and hundreds of clubber passion projects. Those tools include Hackathon.zip, an all-in-one platform for hosting hackathons, and Hack Club Bank. The latter encourages Clubbers to get their projects off the ground by giving them a bank account and transparent ledger so that funders can see where every dollar is spent. Ian still has a few years until college, where he expects to major in computer science. But he feels readier. “I think I’ll be better prepared, not only technically, but professionally.”

Face the Flames

Kevin Yang loves to make stuff. The “what” is less important. At 17, he and friends created a flamethrower from a taser, some sunscreen, and a toy guitar. In true hacker fashion, they were out in the woods without access to conventional electronics, so made do with the remains of an old R/C car and other scavenged items — and they created fire. Kevin started working on circuit boards in middle school, with mixed results. “It was a very lonely, intensive, and difficult adventure. They were expensive to manufacture, I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t have anyone to talk to.” To remedy this, Kevin teamed up with a Hack Club engineer, Max Wofford, to create OnBoard, a grant program that allows teenagers to design their own circuit boards. He’s now working on building out the program’s tutorials to help ensure that students have all the resources, guidance, and support he wished he’d had.

Ships and Makers

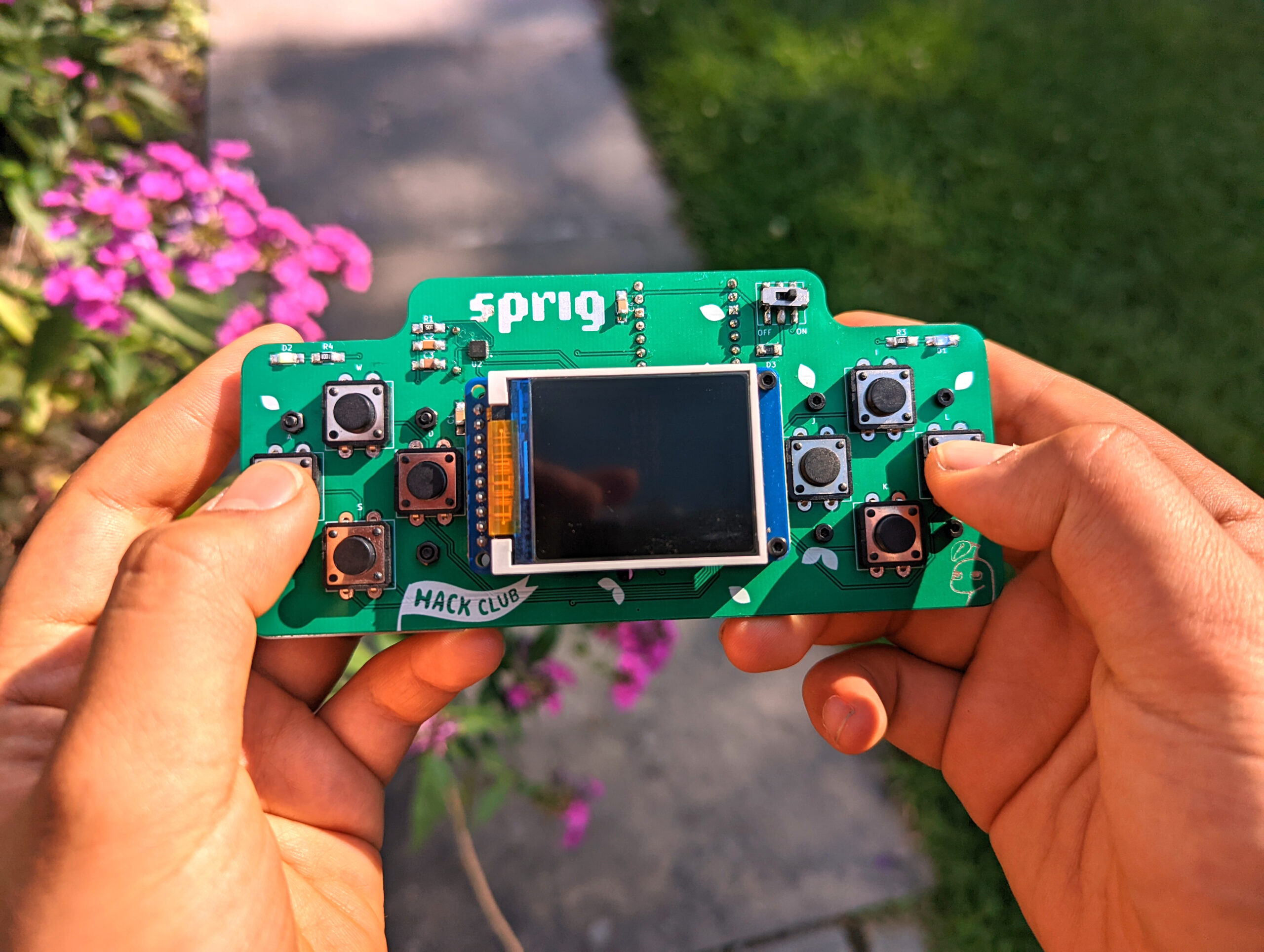

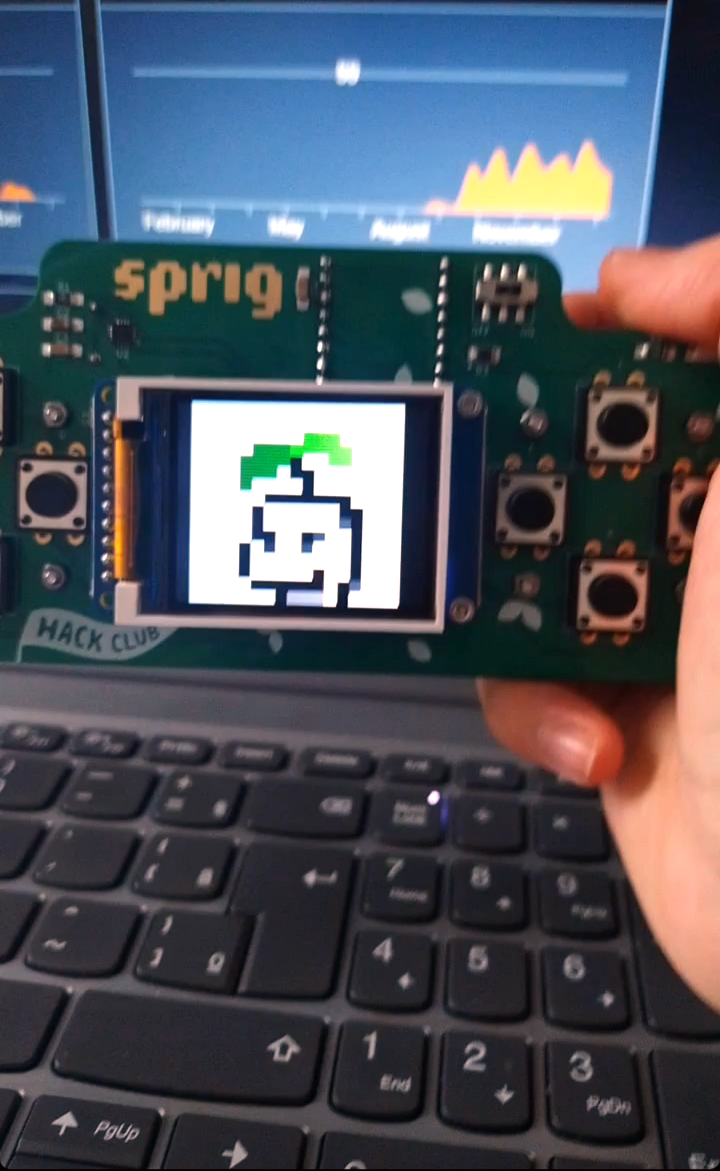

One need that arose as Hack Club grew was creating materials for teens unable to access a local club. Hack Club engineer Leo McElory, a makerspace wizard and creator of the Gram drawing language, worked with Cedric Hutchings, a crack coder hired right out his Appalachian high school, to design Hack Club’s first “You Ship, We Ship” project, Sprig — a web-based editor that teens can use to draw, make music, and craft their own tile-based games. Once clubbers “ship” their creations by publishing them online, Hack Club mails them back materials for a miniature console to install them on: a Sprig kit that anchors two D-pads, an audio controller, and a 160×128 color LCD to a Raspberry Pi Pico. Lucas Honda, 15, from Sao Paulo, Brazil, joined Hack Club in 2022. One of his first self-assigned projects was building and uploading Flurffy, a JavaScript-based Sprig game with echoes of the original Flappy Bird. But his biggest reward wasn’t just the positive reviews from his new friends; it was establishing himself in a community where he could help other young folks to build games of their own.

Art is Math

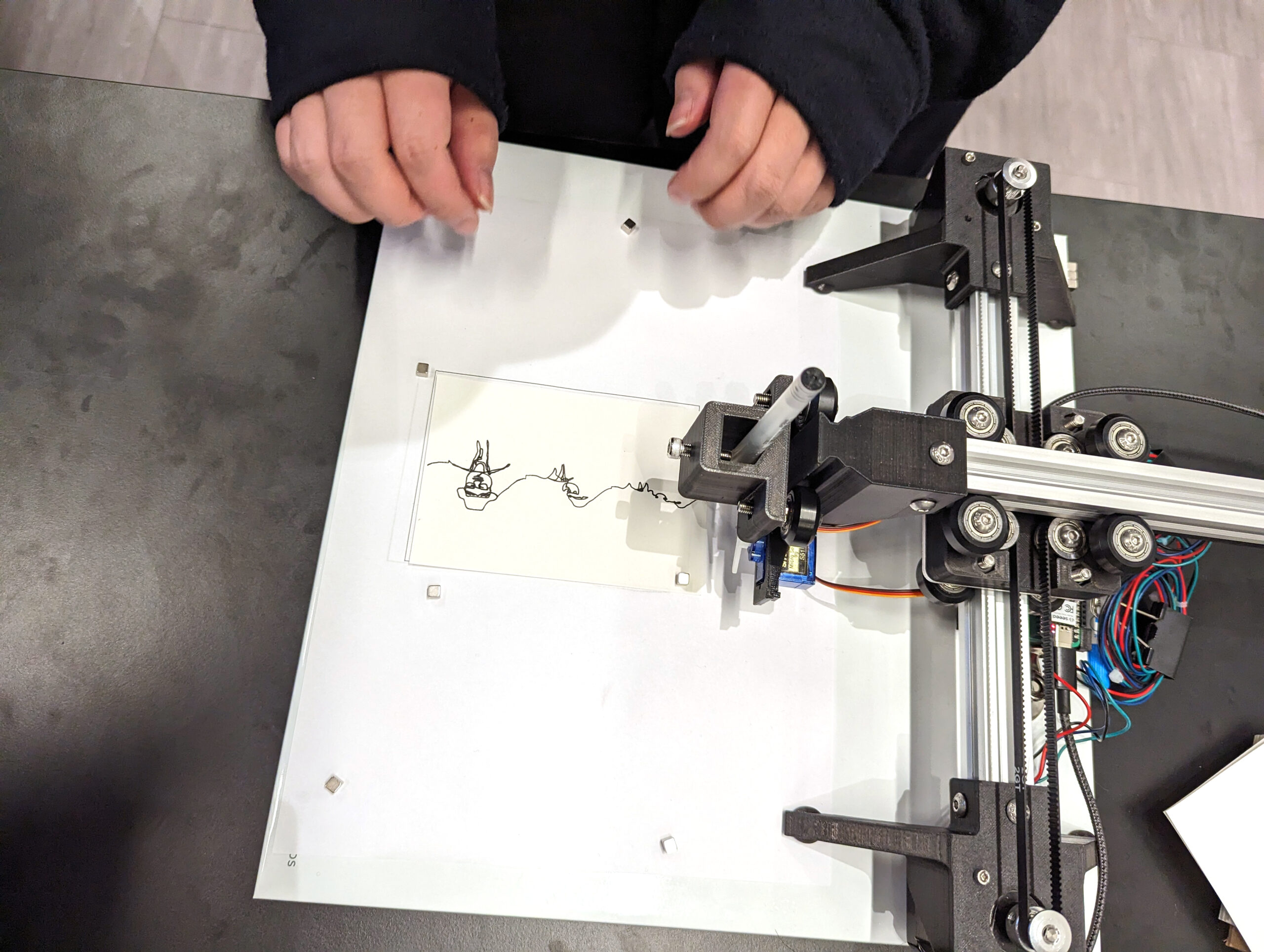

Bright Li, a ninth grader from Southern California, was born to two software engineers, who encouraged his tinkering, including taking apart an old phone to examine its circuits and reverse engineer how its touch technology worked. Bright also contributes to another of Hack Club’s beta You Ship, We Ship projects, Blot, which brings digital art into the physical world. Clubbers use a custom web editor to write a program that creates a piece of art, and Hack Club then sends out a CNC machine kit that draws it. Bright is currently working on adding animation features to the editor, and on a music engine.

Everyone is Awesome

Zoya Hussain is from Dallas, Texas. Her father, who’d come to America from Pakistan, filled her childhood with stories about computers, and helped her break down robots to understand the engineering and design inside. She was quickly hooked. Though already familiar with hackathons — of which she’d won four consecutively — she noticed something special about the ones Hack Club ran: “I’d never seen a team invest this amount of collaboration with an emphasis on creating a magical event. It’s taught me something about how events should cater towards the people they’re serving, and how to do that practically.” This especially matters for girls. STEM is still only about 20% female, and changing this starts with inclusion made practical. This led Zoya towards Hack Club’s Days of Service project, which hosts one-day hacking events to get girls not just into coding, but into a supportive community where they won’t feel like imposters. Alongside her other engineering projects, Zoya is now able to help more of those girls share her own realization: “An entire world was revealed to me that I never knew existed. I wasn’t sure before that anything related to computer engineering was really for me. Now I’m sure.”

So how can you get involved?

If you’re a teenager, you can join Hack Club’s online community now at hackclub.com. Adults, we’d love if you could support our programs by donating via hackclub.com/philanthropy!

ADVERTISEMENT