I was in a small room at a game convention last year the moment I first understood the power of virtual reality. It was my first time trying a social VR experience, my first time in a virtual space that I shared with another person. Despite my cohabitant being represented as just a wireframe rendering of a head and hands, the experience was transformative. Within moments, I was interacting with the other person’s avatar as if it was an actual person, noting and interpreting the small body language cues that are lost in other forms of communication, like video or phone calls.

If I could read body language from an avatar with no limbs, no eyes, and no mouth, a more realized avatar could convey real human emotion. TV, film, web video, and more were all about to change. It took a while for me to realize it, but that was the moment that lead to me quitting my amazing job at Tested, and starting a company to build VR software. That was the moment I realized that you’d be able to tell incredible stories in virtual worlds.

I wanted to build those worlds. That’s what we do at FOO VR, with our first being a virtual talk show called The FOO Show.

I’m getting a bit ahead of myself though. At the lowest level, VR is transformative because it represents a more natural way for humans to interact with computers. The human brain innately understands three-dimensional worlds because 3D is our native environment — every conscious moment of our lives is spent in a three dimensional world, the real world.

“But,” you say, “I’ve used 3D applications on my computers for 20 years.” That’s absolutely true… from a certain point of view. When you use a 3D application, whether it’s a game or a CAD program, on a traditional computer monitor you’re actually looking at a 2D projection of a 3D scene. We’ve built 2D interfaces that work around this limitation, and we use some tricks to add the illusion of depth to those 2D projections, but when you look at a 3D object on a 2D monitor, it’s still akin to looking at a shadow and trying to determine the 3D shape that cast it.

I’ve always had trouble working in the traditional CAD interface, or using the XY/YZ/XZ window convention of most 3D modeling programs to create the object I’m visualizing. The first time I used a sculpting or drawing program in VR, I didn’t have to make that mental leap anymore. I was interacting with a virtual object in exactly the same way I could interact with actual objects in the real world, but with the benefit of multiple save files, copy and paste, and an undo/redo chain.

The upshot: It is much easier for me to manipulate objects in VR, using my hands, than it is to do the same in a CAD-like window in a more traditional 2D application.

One of the unexpected, but interesting side effects of the 3D-native nature of your brain is that things that aren’t particularly fun in traditional games are much more entertaining in VR. People love exploring VR environments, picking up and inspecting props and set dressing, and performing even the simplest of physics-based actions, like throwing a paper airplane.

At this point, I’ve demoed our software to hundreds of people. Because of that, I’ve given many people their first taste of real VR, and boy is that fun. However, the big lesson from those demos is that …

Having Hands in VR Is Important

Using a gamepad or mouse and keyboard to control a VR experience is kind of like trying to write your signature using a mouse. It’s clumsy, doesn’t work the way you’d expect, and can leave you frustrated at the whole process. On the other hand, people immediately grok how to use hand controllers to interact with virtual environments. If you have them squeeze and hold a trigger to pick something up, then you’ve taught them more than just how to grab something; you’ve also shown them how to hand it to someone else or throw it across the room, and you’ve set up the opportunity to layer on more advanced tasks, like sorting many objects, hiding them, or even shrinking or enlarging them.

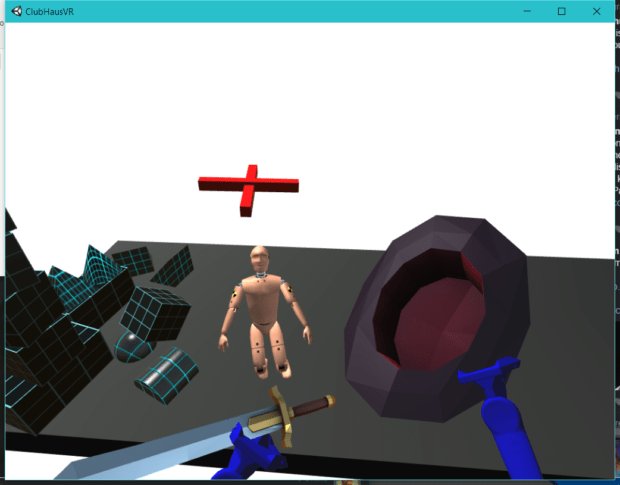

For VR developers, the downside of giving your users hands is that the users expect VR environments to be more interactive than a traditional game. When we populated our test world with some small props, the first thing people tried to do was pick them up. When we let people pick those objects up, they tried to throw them. When we let them throw them, they expected them to bounce and interact with other objects. We wouldn’t have figured out that people expected all this, but luckily, we …

Test Early and Test Often

Remember when I said I’ve run a few hundred people through our VR demos? That wasn’t just for fun. Every time we showed someone new what we’d built, we used that as an opportunity to get feedback on our software. It’s good to set up so you can see both the user and the monitor with what they’re seeing on it.

a tight 20’×20′ space. Photo by Eric Florenzano

Sessions in VR can be long, and I don’t like to interrupt anyone to ask questions when they’re in the goggles, so it’s really important that you take good notes as you watch the tester. This lets you prompt your testers with specifics about their experience once they’ve taken the goggles off.

The big takeaway here is that everyone reacts differently to different experiences in VR, so get as many people to try your software as you can. And above all …

Don’t Make People Sick

Our number one rule is: Avoid making people sick, at all costs. Yes, the alcohol and theme park industries have made bank by making their customers hurl, but I don’t ever want to be responsible for ruining someone’s day. Because VR software has such an intimate connection to your user’s brain — it takes over two senses entirely — developers have a greater responsibility than with most traditional software or games. I’m not suggesting that there’s any Lawnmower Man-style reprogramming possible with VR, but bad or malicious software definitely can make users feel extremely uncomfortable.

When most people sense a disconnect between the movement they see and the movement (or lack thereof) they detect with their inner ear, they start feeling motion sickness. That discomfort builds the longer you stay in the headset — the only way to get a reprieve is to take a break.

The good news is that VR-related motion sickness is avoidable for almost everyone. As a developer, it’s your responsibility to ensure your application never sags below the target frame rate for your platform and to avoid moving the player’s camera in ways that will make them feel ill. To be safe, we never take control of the camera from the user.

Every question about VR we answer just begs another dozen questions. Many of the lessons we’ve learned from decades of traditional software development don’t apply to VR, so we need people who are excited about the possibility and ready to create new solutions to problems we haven’t even imagined yet. If you’d like to know more, we regularly share our findings at the FOO blog.

If you’d like to check out what we’ve built, search for The FOO Show on your VR headset’s storefront, we’re on Oculus and Vive right now, and may be on Gear VR and PlayStation VR by the time you read this.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on Medium and is reprinted here and in Make: vol. 52 with permission of the author.

ADVERTISEMENT