With the explosion of inexpensive remote-controlled aircraft combined with high-resolution digital cameras, it may seem that we’re in the heyday of aerial photography. But people have been taking pictures from the sky almost since the dawn of the camera itself. Even before Orville and Wilbur took their famous jaunt around the skies outside Kitty Hawk, cameras were occupying the airspace through the use of the most low-tech of lifters: the kite.

Not everyone has the thumb coordination to fly a quad copter, and few have a pilot buddy who can carry them skyward, but just about anyone can fly a kite. The hobby of Kite Aerial Photography (KAP) has been given a new wind with the advent of affordable, light-weight action cameras and advanced remote-controlled devices. Even though it’s been over a hundred years since George Lawrence took his famous panorama of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake, the kite is still the simplest way to get a lofted perspective for your photography.

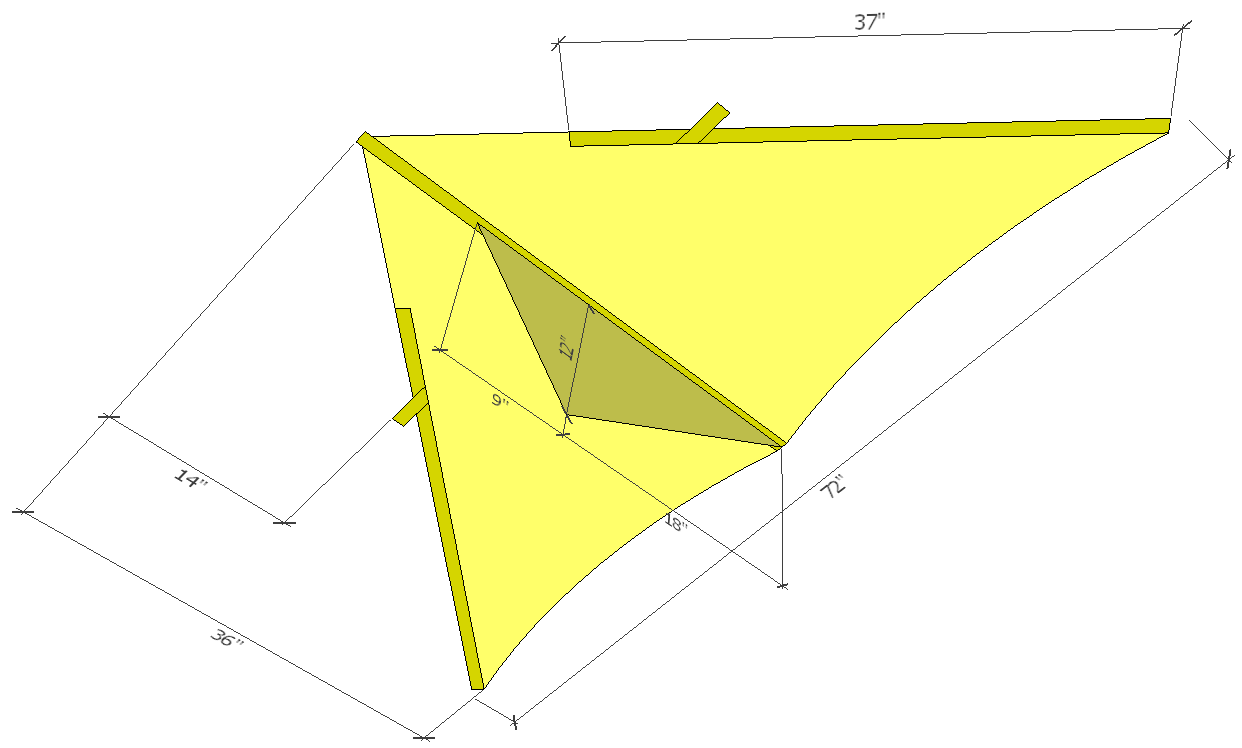

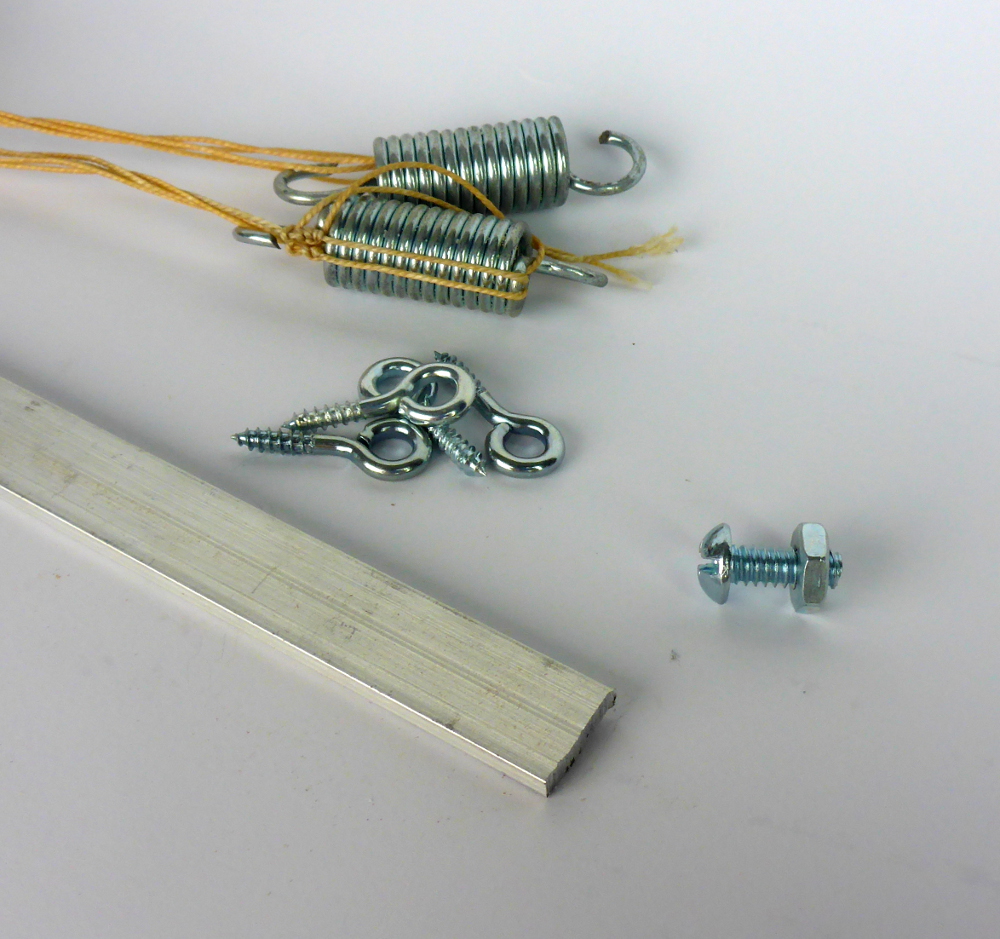

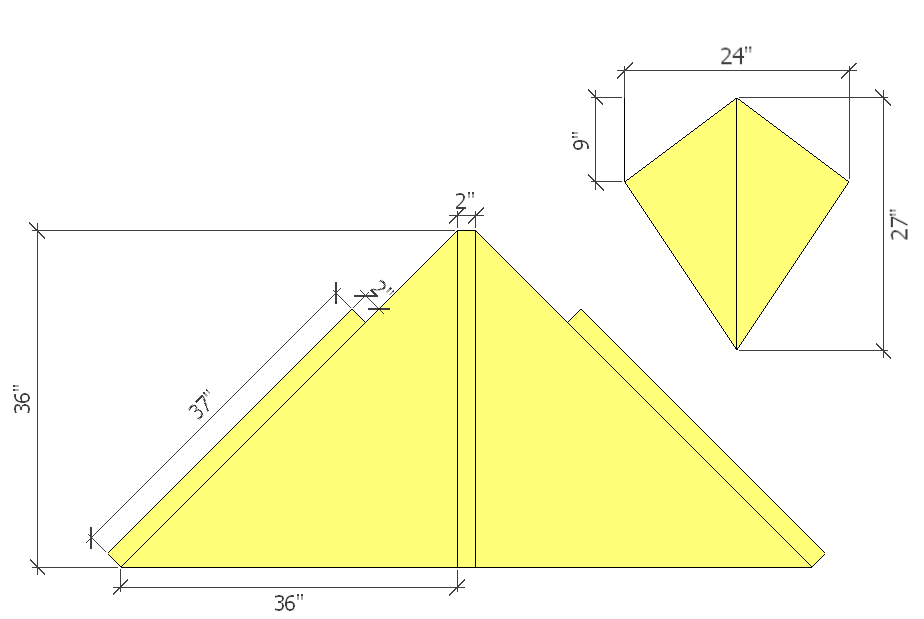

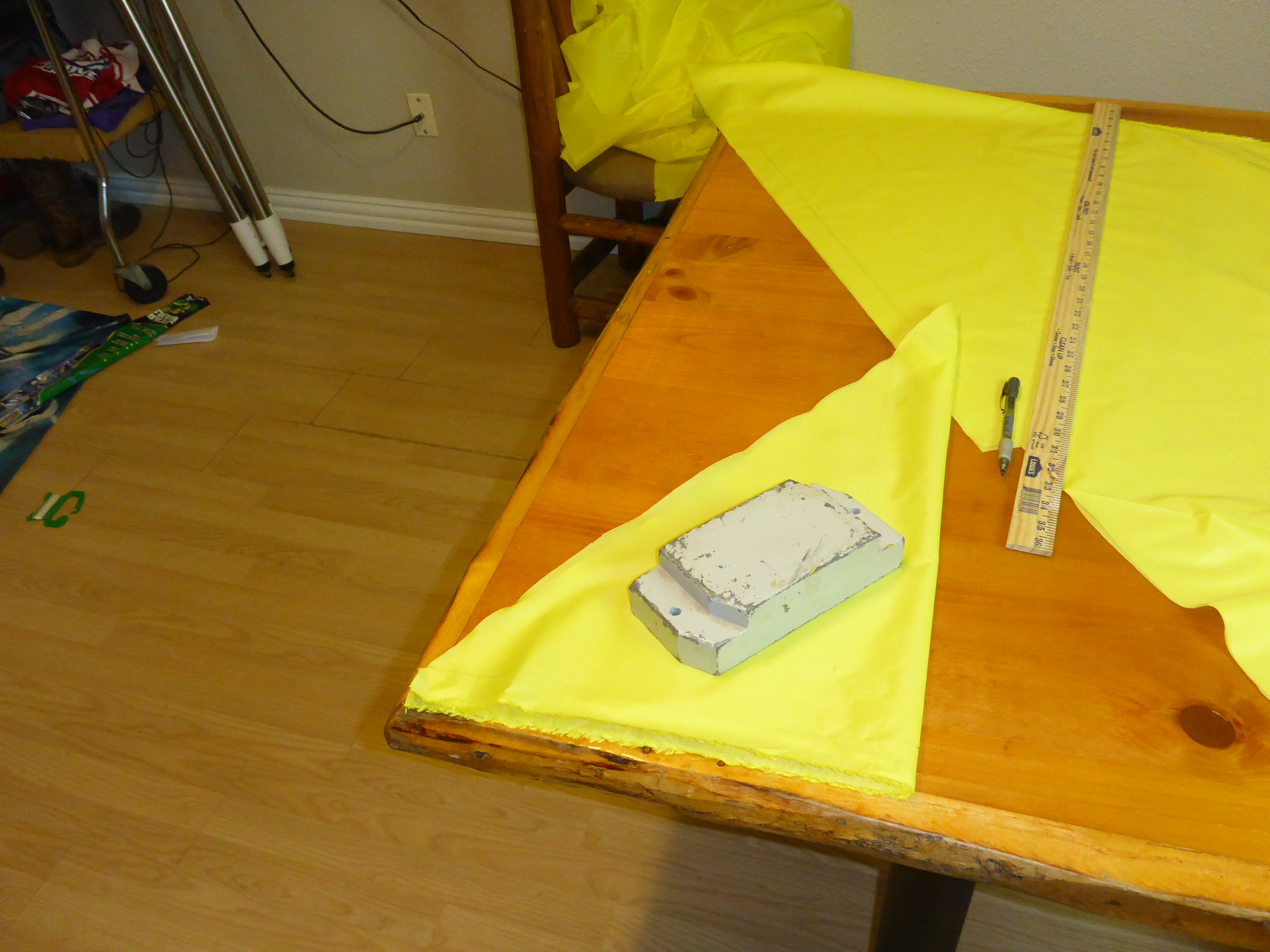

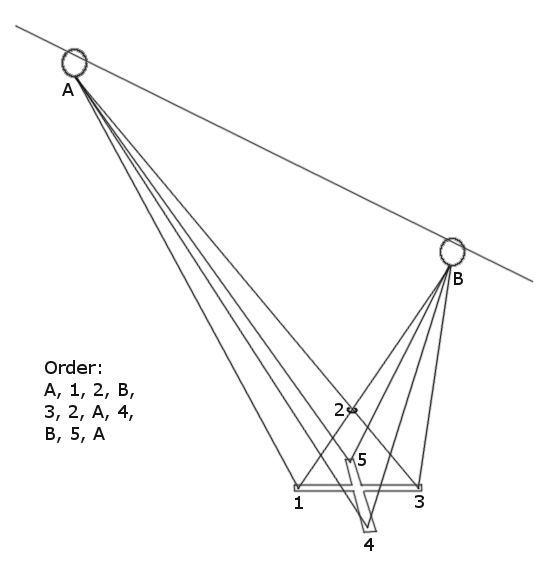

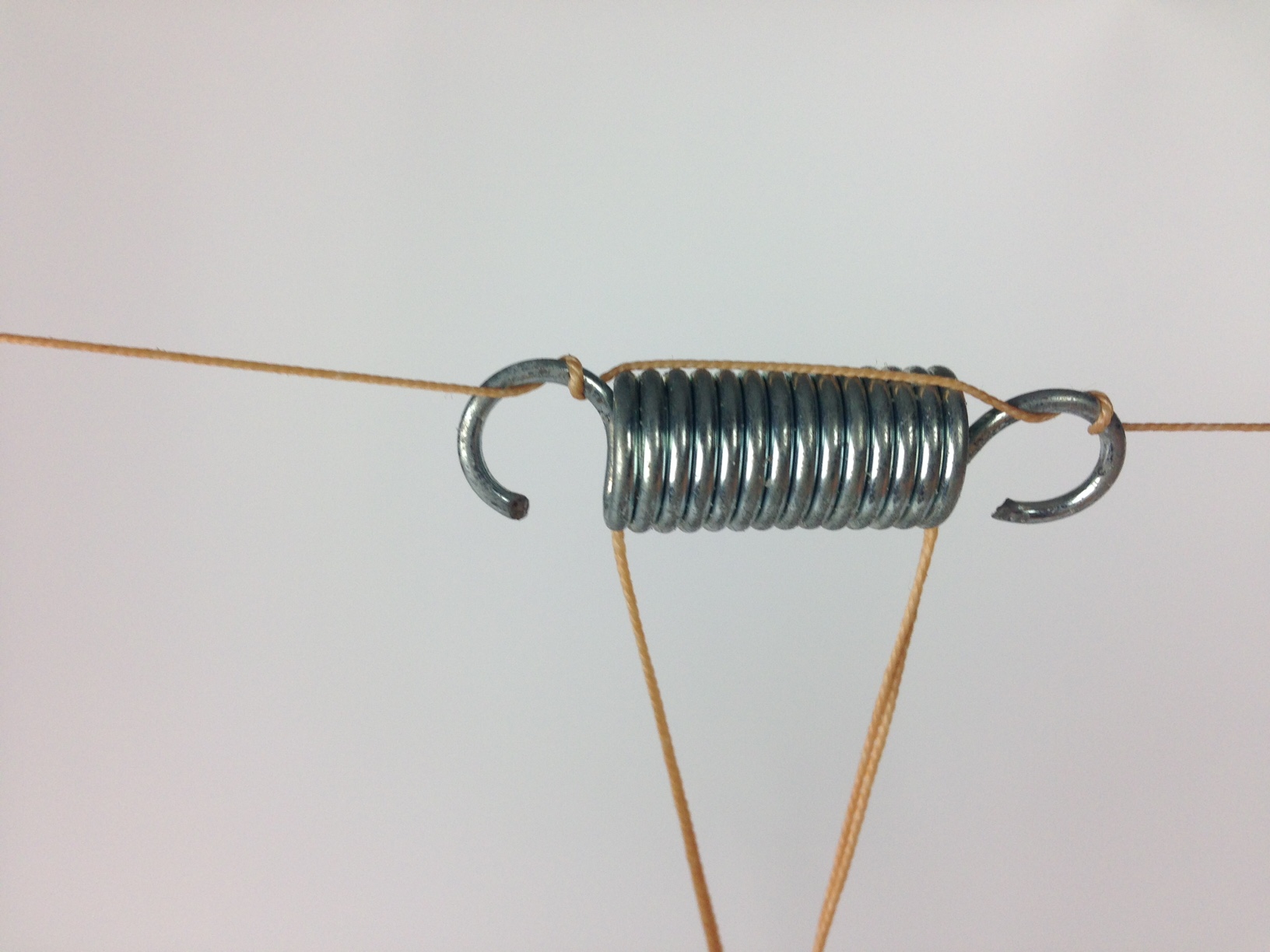

The kites you can pick up at a big-box store aren’t meant for heavy lifting, but a good-quality kite can go for hundreds of dollars (not to mention the camera mount). You can put together a full homemade KAP rig for a fraction of that cost with materials that you can pick up from the local hardware store and the fabric shop. No special tools or skills required. Just add your favorite camera (or maybe your second favorite camera, depending on how much you trust your handiwork).

Note: Like just about any hobby, one could spend a lifetime learning the intricacies and minutiae of kite building. This tutorial barely scratches the surface of the information available on this rewarding pastime. If you’re craving more information, the forums on KiteBuilder seem to be the most active that I could find.