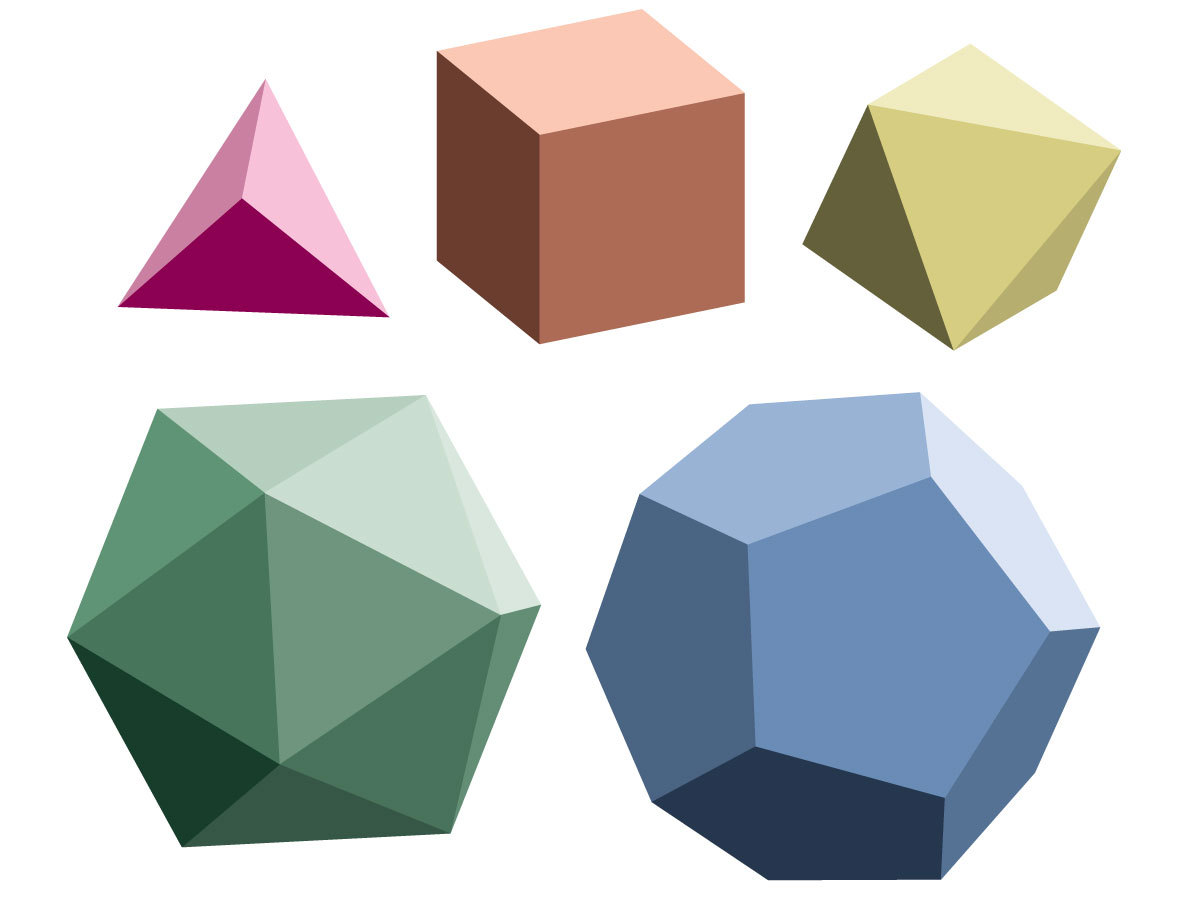

People appear symmetrical, but even the most perfect human face shows irregularities if we compare the left side with the right. Perhaps this is why the absolute, rigid symmetry of crystals seems beautiful yet alien to us. Unlike DNA’s soft spiral, a crystal’s molecular bonds align themselves to form regular three-dimensional structures, which the Greeks considered mathematically pure. The most fundamental of these shapes are known as the five Platonic solids.

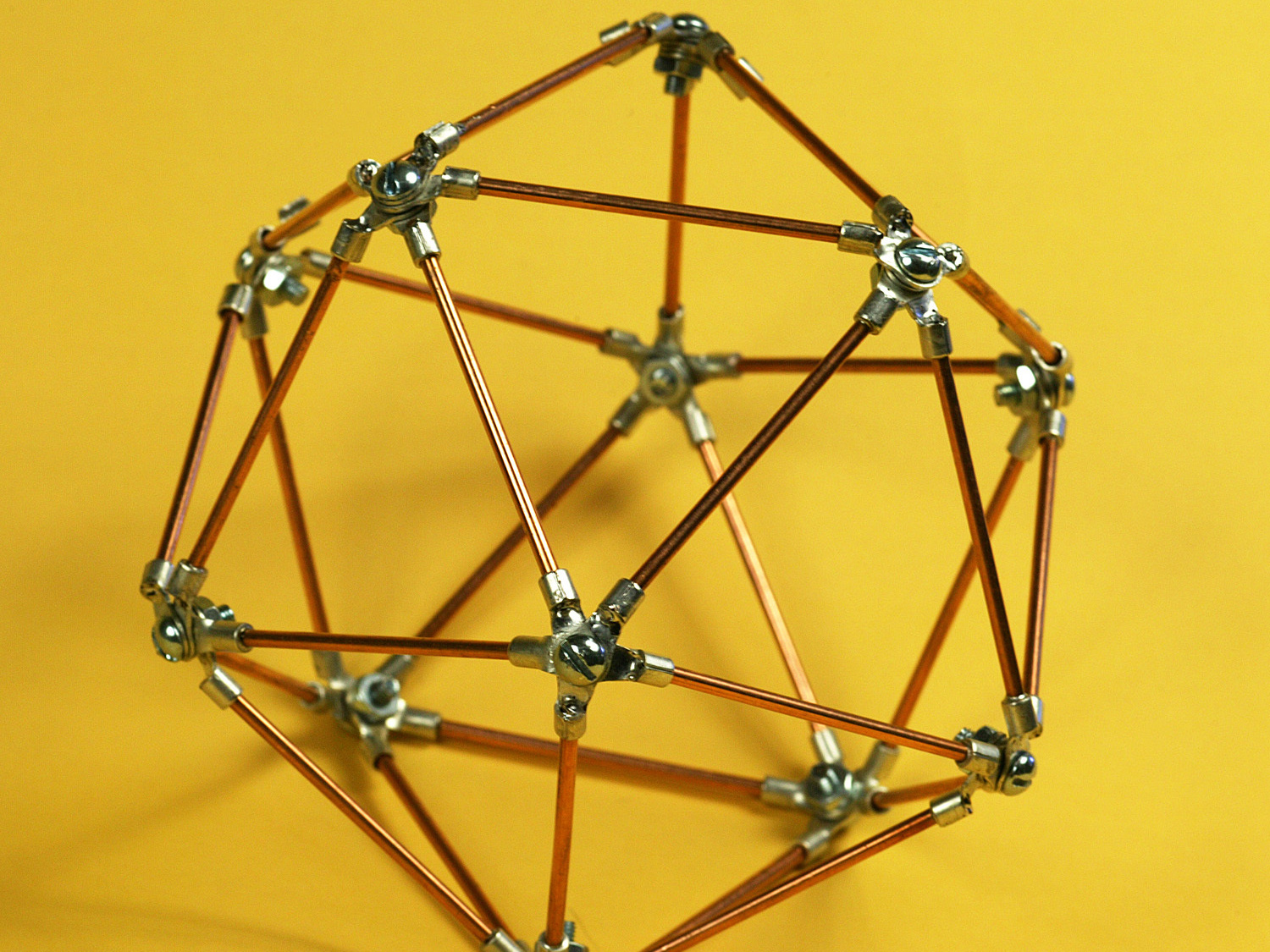

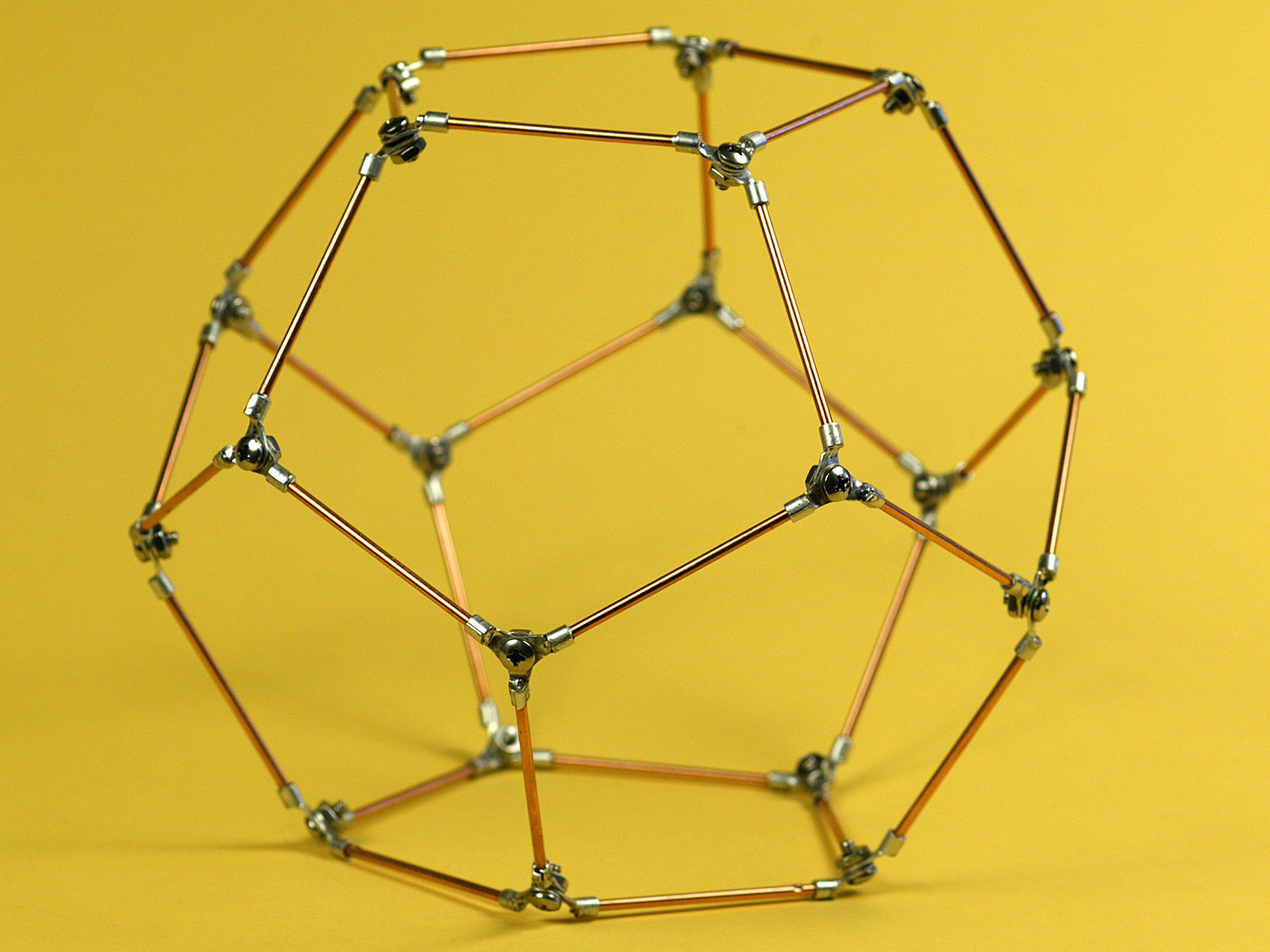

If you assemble equal-sided triangles — all the same size, with the same angles to each other — you can create three possible solids: a tetrahedron (with 4 faces), an octahedron (8 faces), and an icosahedron (20 faces). If you use squares instead of triangles, you can create only a hexahedron, commonly known as a cube. Pentagons create a dodecahedron (12 faces), and that’s as far as we can go. No other solid objects can be built with all-identical, equal-sided, equal-angled polygons.

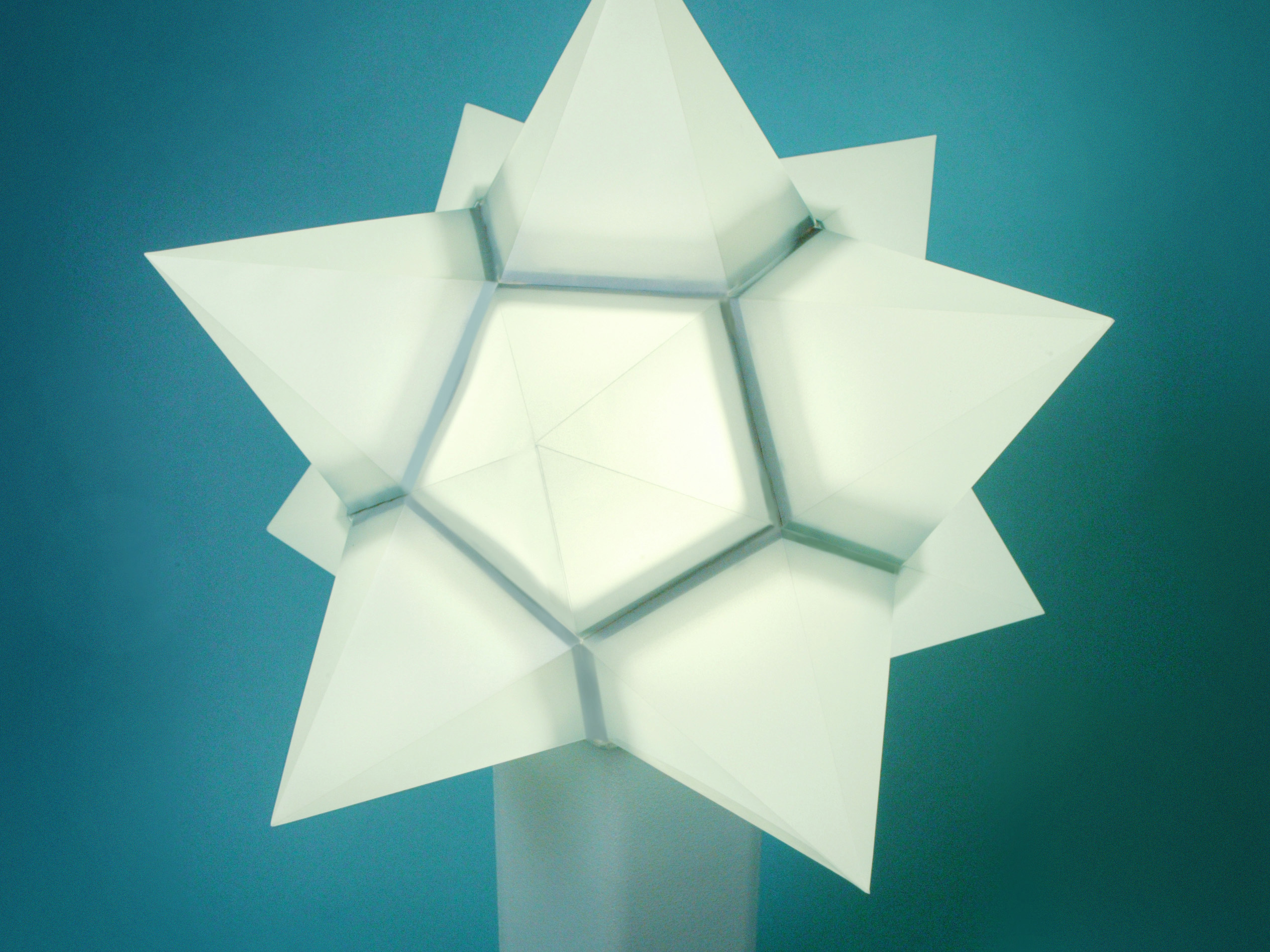

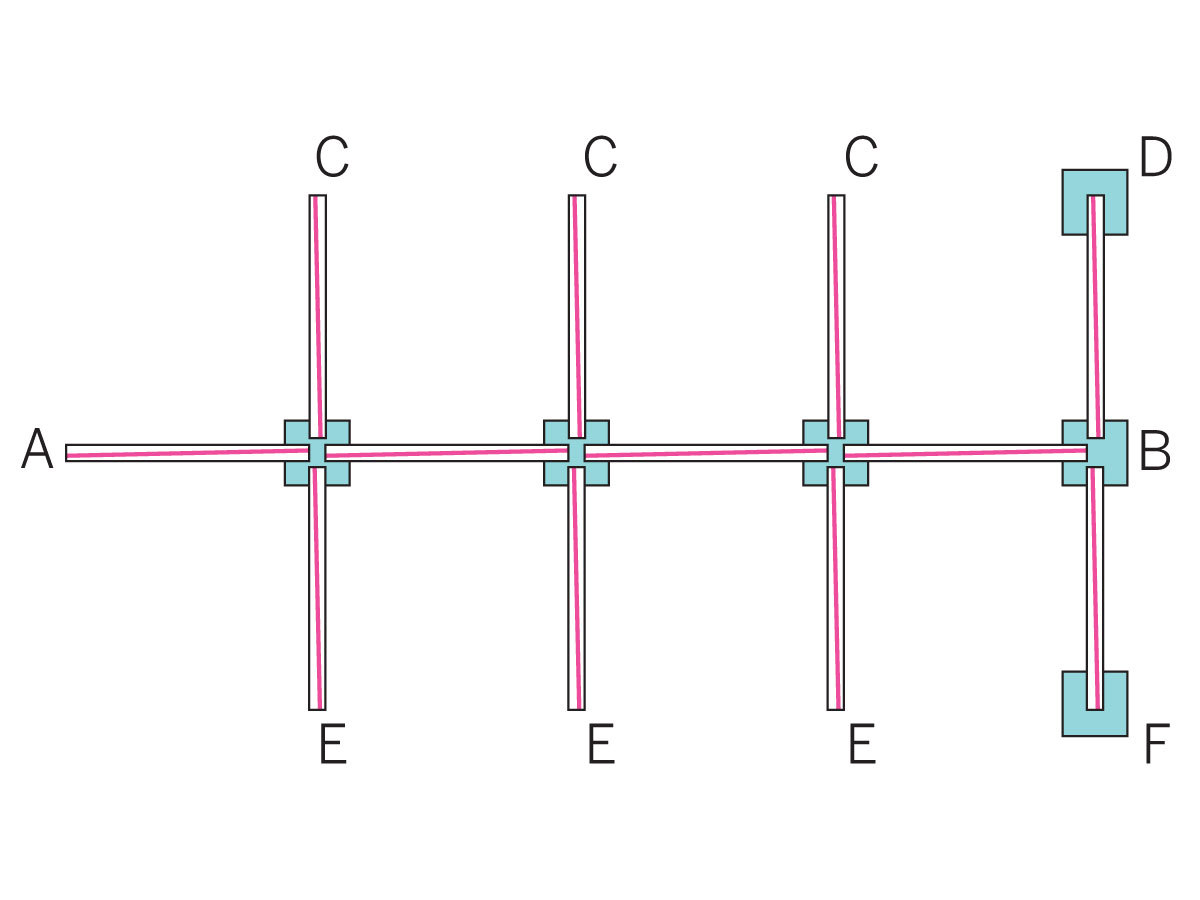

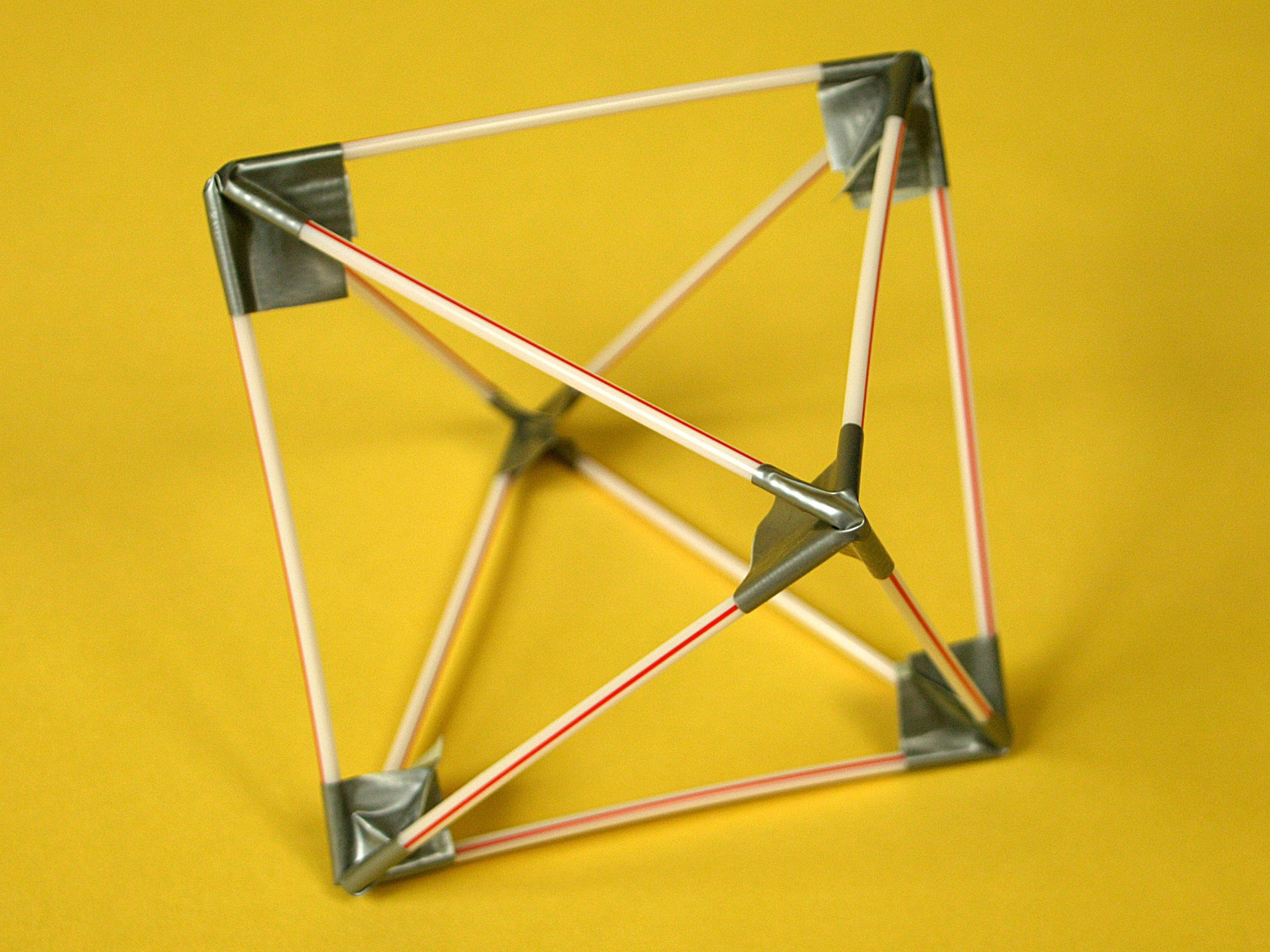

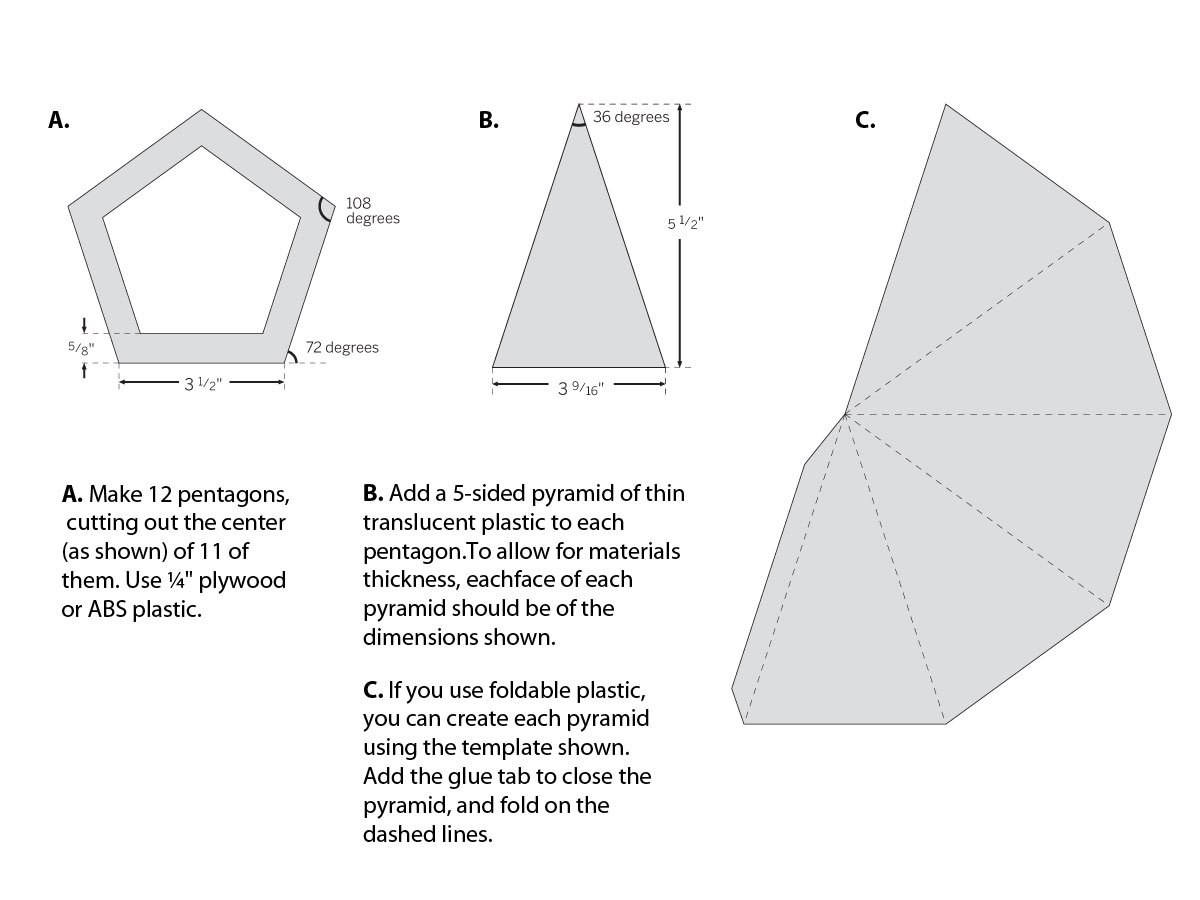

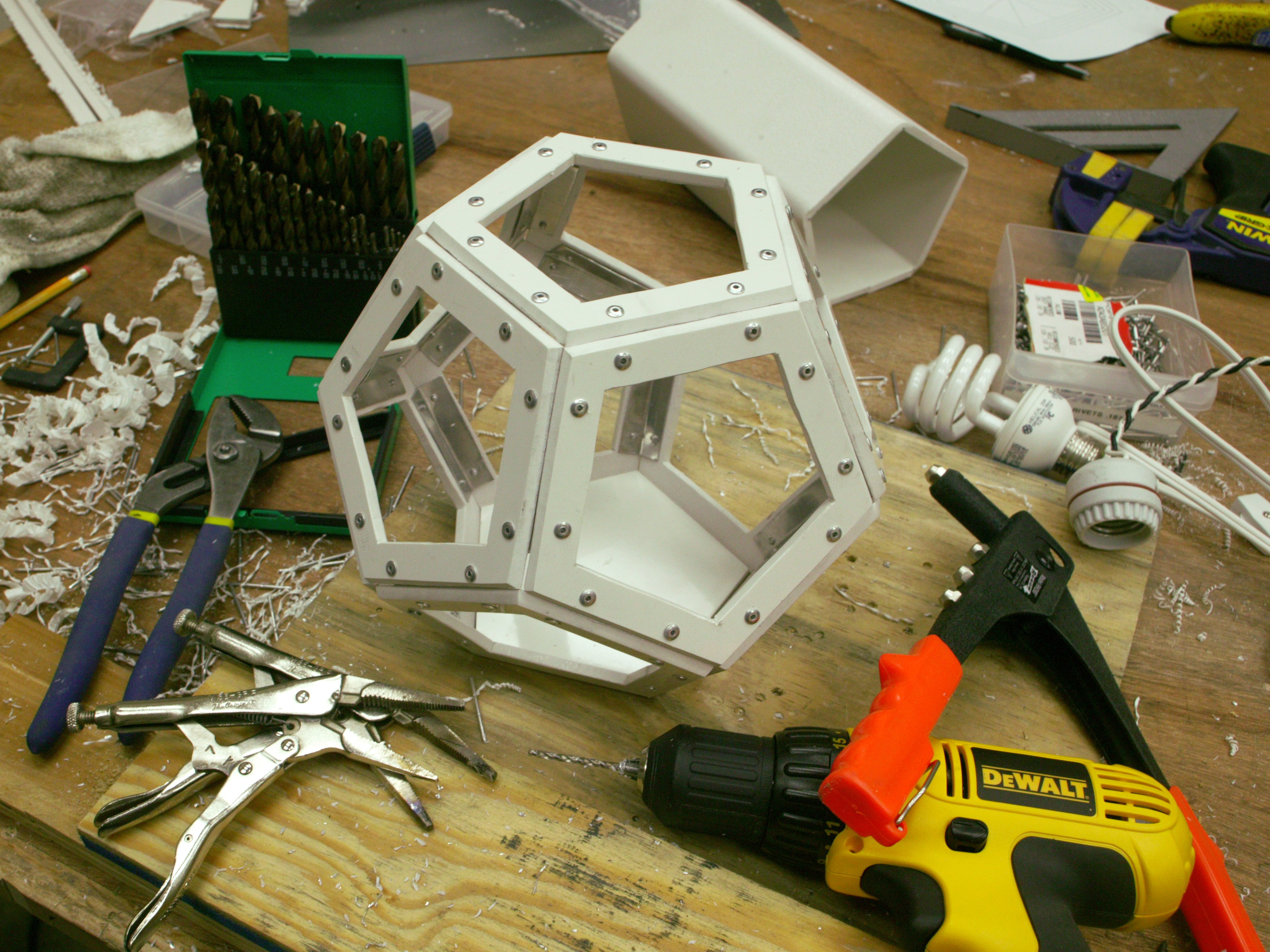

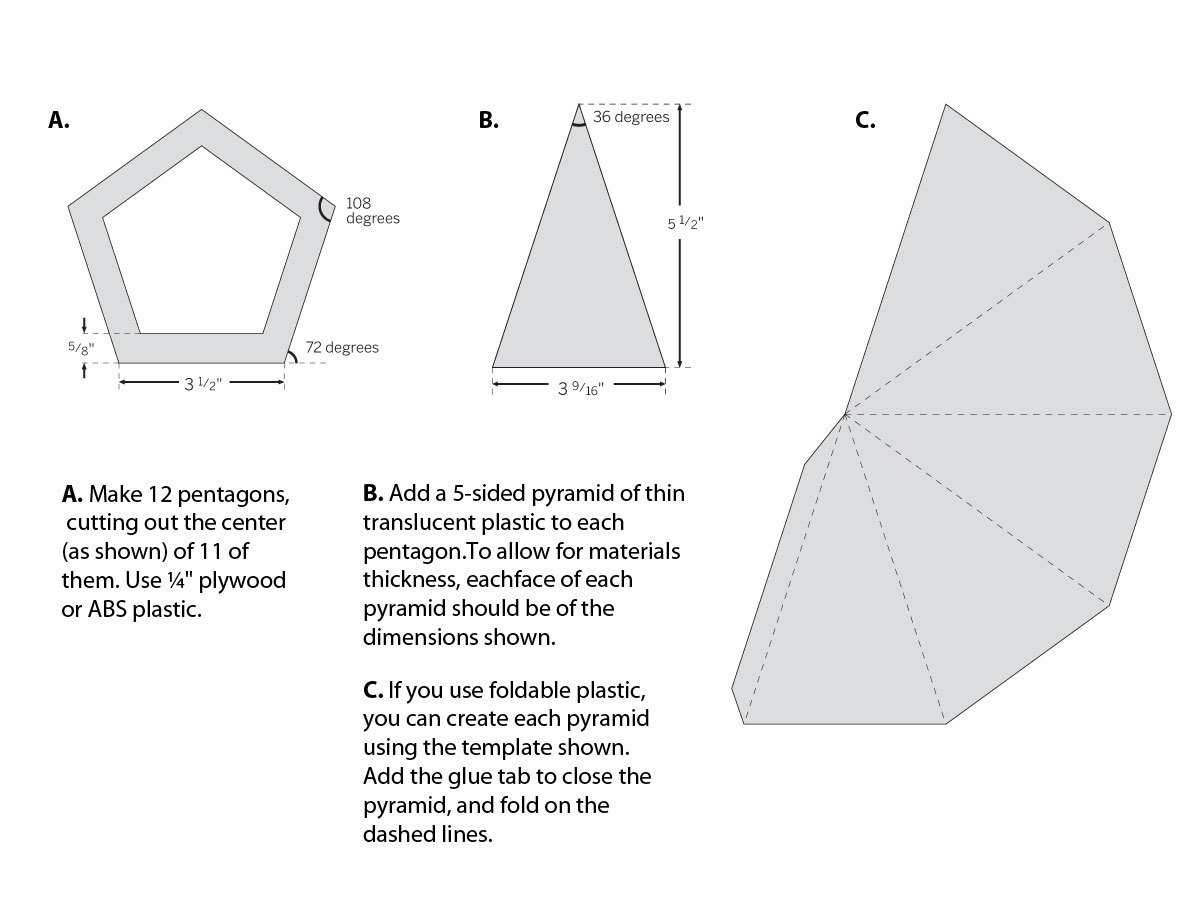

The Platonic solids have always fascinated me. My favorite is the dodecahedron, which is why I used it in this project as the basis for a table lamp. By extending its edges to form points, we make something that looks not only mathematically perfect, but perhaps a little magical.