The big video game companies create best-selling titles every year, but for the rest of us, bringing our own unique game ideas from wishful thinking into reality is notoriously difficult.

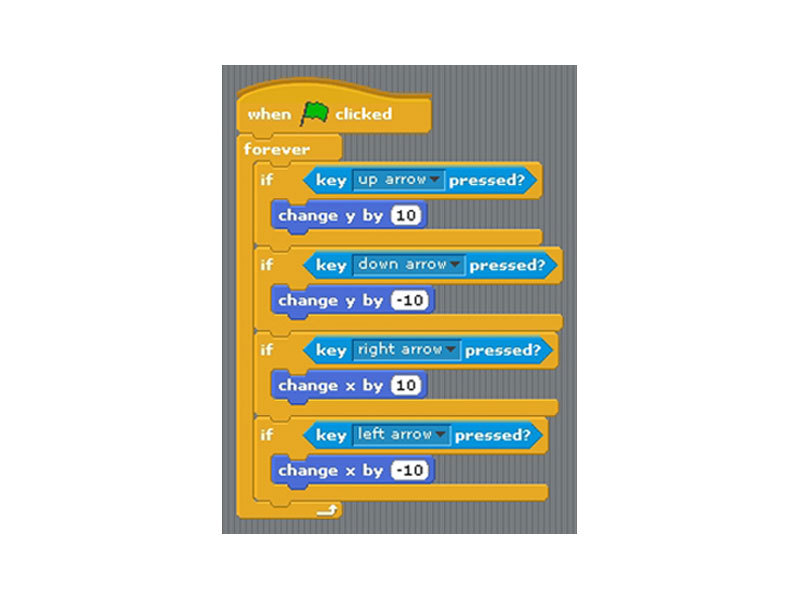

Creating even the simplest functionality can take tens of thousands of lines of code. Luckily, the MIT Media Lab has created free software, Scratch (scratch.mit.edu), that lets kids create their own games or interactive stories using an easy drag-and-drop interface and some elementary programming.

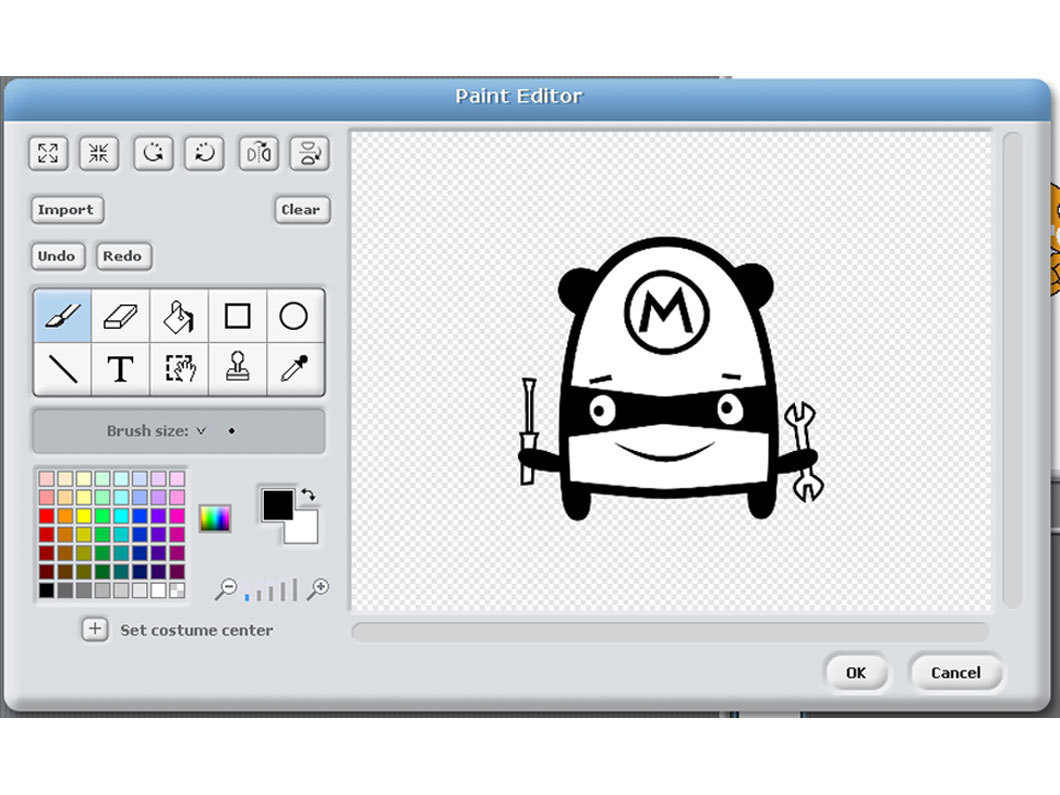

Download, install, and launch Scratch, and soon you’ll be creating simple “side-scrollers” — games like Super Mario Bros., where characters navigate obstacles left-to-right. You can also make your characters communicate via speech balloons, like an animated cartoon. Scratch makes no distinction between games and animations; it’s all in your programming.