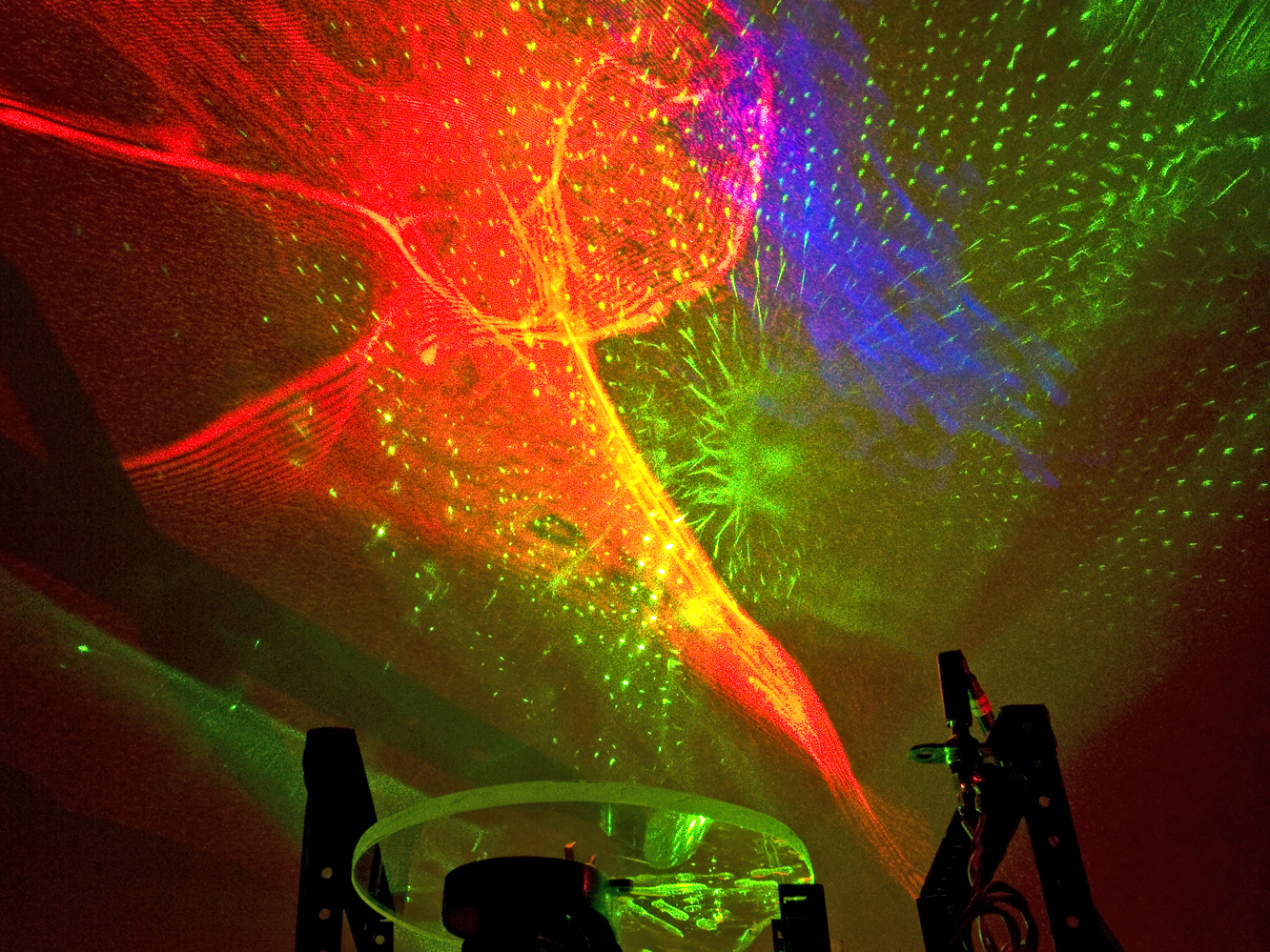

Back in the 1970s, my friend Wayne Gillis and I used to do light shows at science fiction conventions. We had the usual panoply of overhead, slide, and custom-made projectors, and a single, very expensive, helium-neon laser from Edmund Scientific. Calling ourselves Light Opera, and later, Illuminatus, we performed at ConFusion conventions in Ann Arbor, Mich., and at the World Science Fiction Convention in 1976, where Robert Heinlein was guest of honor.

Flash forward 30 years, and I get a call from David Bloom, a web marketing/connection guy and awesome keyboardist. Would we like to revive our act and perform with him at Penguicon 7? You betcha, I said, and Wayne and I set about to update our craft, revive our spent youths, and order a bunch of now-inexpensive lasers. Thus Illuminatus 2.0 was born.

Penguicon is a unique convention that mixes science fiction fans with those deep into open source software. Given the open nature of the event, we decided to share our tech with MAKE readers interested in laser displays and soldering.

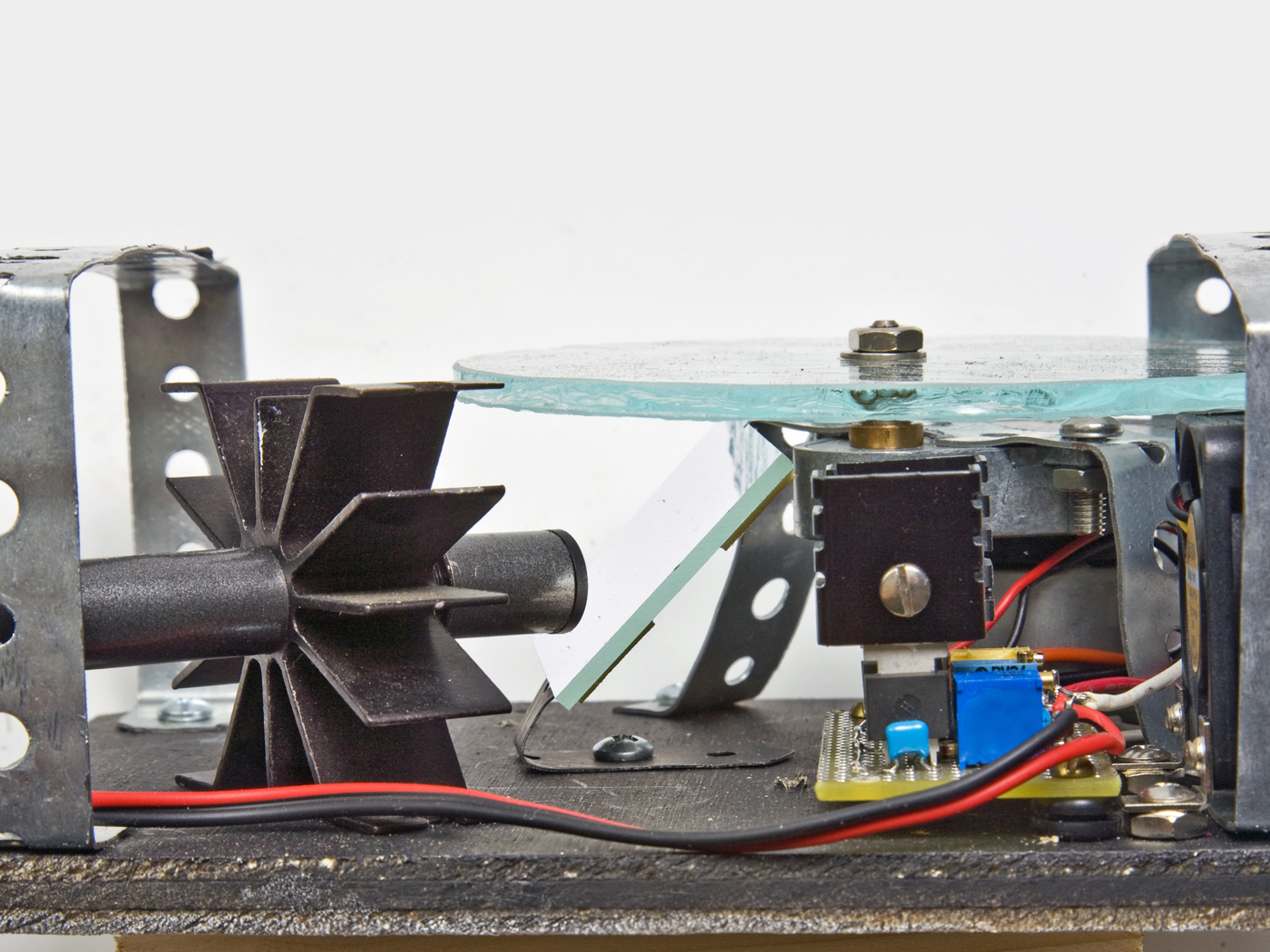

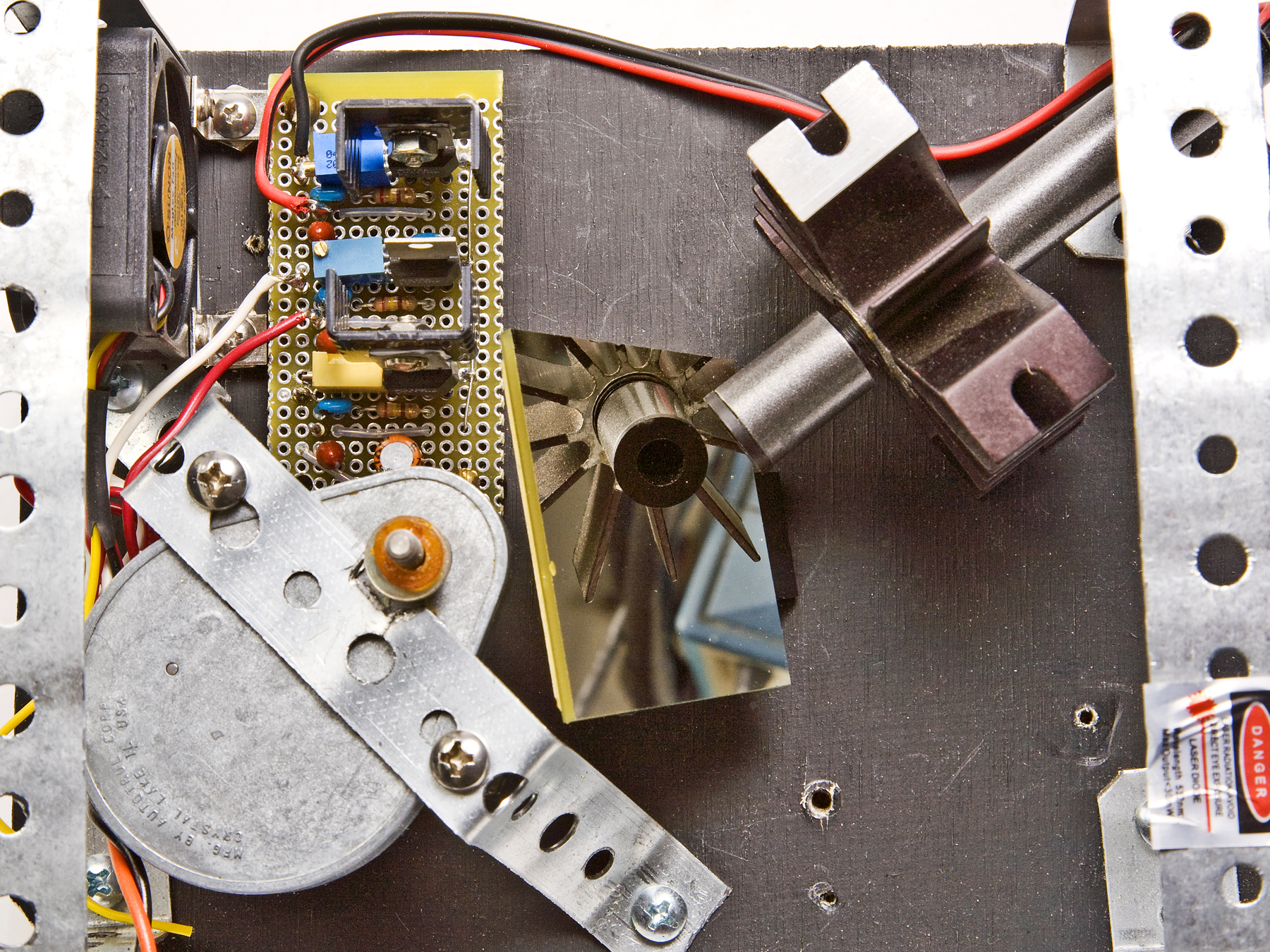

Instead of a single, monolithic laser device, we went with a bunch of inexpensive units, and as “cheapness” was the watchword for this project, we housed the devices in the cheapest metal boxes we could find, namely, lunchboxen. (Penguicon is a Linux convention, so it’s one box, two boxen). A search of eBay turned up a raft of cool boxen with science fiction themes, and we were on our way.