I’ve enjoyed capturing timelapse videos ever since I found myself in possession of a camera that could do them. I love the way they transform the mundane into the surreal, whether it’s the ability to see a transformation taking place that’s too slow to observe with the naked eye, or to witness the haphazard nature of our daily lives unfold at breakneck speed. I even carry a small tripod kit with me wherever I go so I can film them with my phone when I have a short wait.

The best way to take your timelapse videos to the next level is to move the camera while it is capturing them, but this is tricky to do unless you have some sort of fancy motion controller. A few years ago, I designed a device that allowed you to pan a camera while it was capturing a timelapse. It was great, but I really wanted the ability to translate, or dolly the camera through space, as it was filming. Years later, and after many ill-conceived and half baked prototypes, I’ve finally built one.

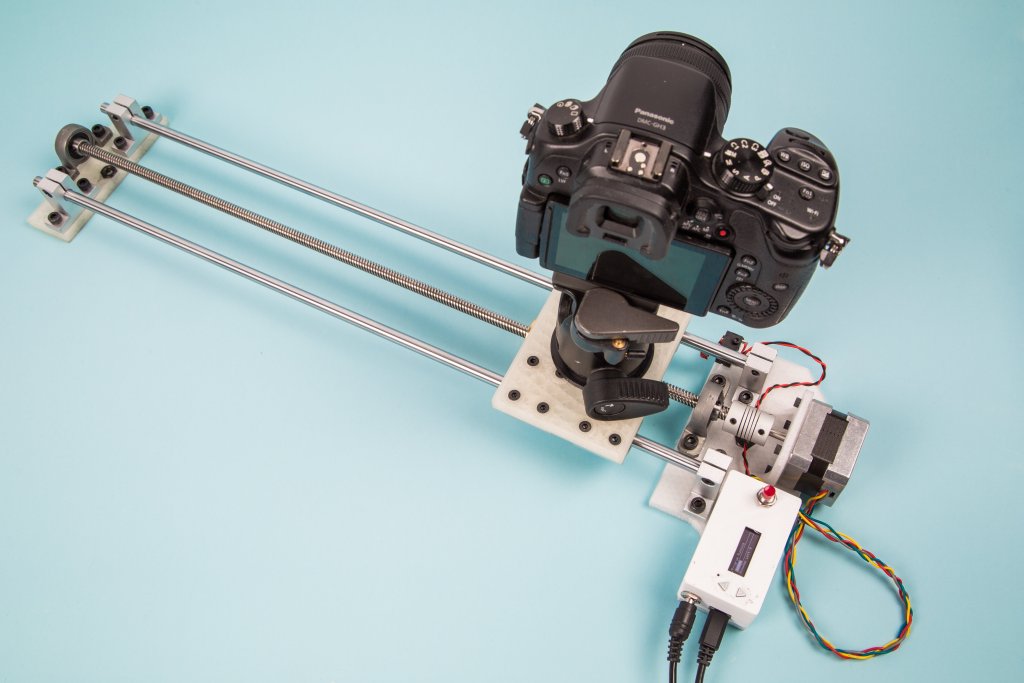

This motion control camera slider will allow you to capture timelapses of anywhere between 5 minutes and 8 hours, and has a span of roughly 500mm. The control unit, motor, and slider mechanism are completely self contained and don’t need any other devices to program the motion.