When invading Germanic tribes deposed the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, in 476 AD, Western Europe fell into a period of intellectual stagnation. The next five centuries were, for European-based science and technology, a very dark age. But the light of science was not snuffed out; instead, it found new places to shine, namely, China, India, and the Arab empires.

The 8th century saw the city of Baghdad quickly grow from a small settlement on the banks of Tigris to a military, commercial, and scientific powerhouse. In fact, Baghdad soon became one of the world’s most important centers for education, culture, and the exploration of science.

The rulers of Baghdad were the caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty (750–1258), and some of them had a deep and abiding interest in technology. They invested a substantial amount in scientific explorations of many kinds.

The best remembered Arabic engineer of that time was Ismail al-Jazari, who was born sometime in the mid-12th century and died in 1206. He is known primarily through his landmark book, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Published just before his death, its pages are filled with a plethora of descriptions of ingenious mechanical devices, along with Make: magazine-like instructions showing how to construct them. Included there are how-to advice and illustrations describing about 100 robotic automata, water fountains, water pumps, and clocks. Like Leonardo da Vinci, who lived 300 years after him, al-Jazari was a polymath adept at many things, and like da Vinci, he is widely remembered for sketches and notebooks of ahead-of-his-time ideas and gadgets.

Modern biographers credit al-Jazari with inventing, refining, or at least anticipating many important technologies. Examples include sandcasting, valve seats, a windproof lamp, plywood, and an automated water flow regulator.

Historians place al-Jazari in the front rank of scientists and engineers from his era. His books are so detailed that many of his devices have been reconstructed by modern makers working from the drawings they contain. Some, like his famous Elephant Clock (Figure A), are so remarkable that several reproductions have been made and currently amaze visitors in museums and other public areas around the world (Figure B).

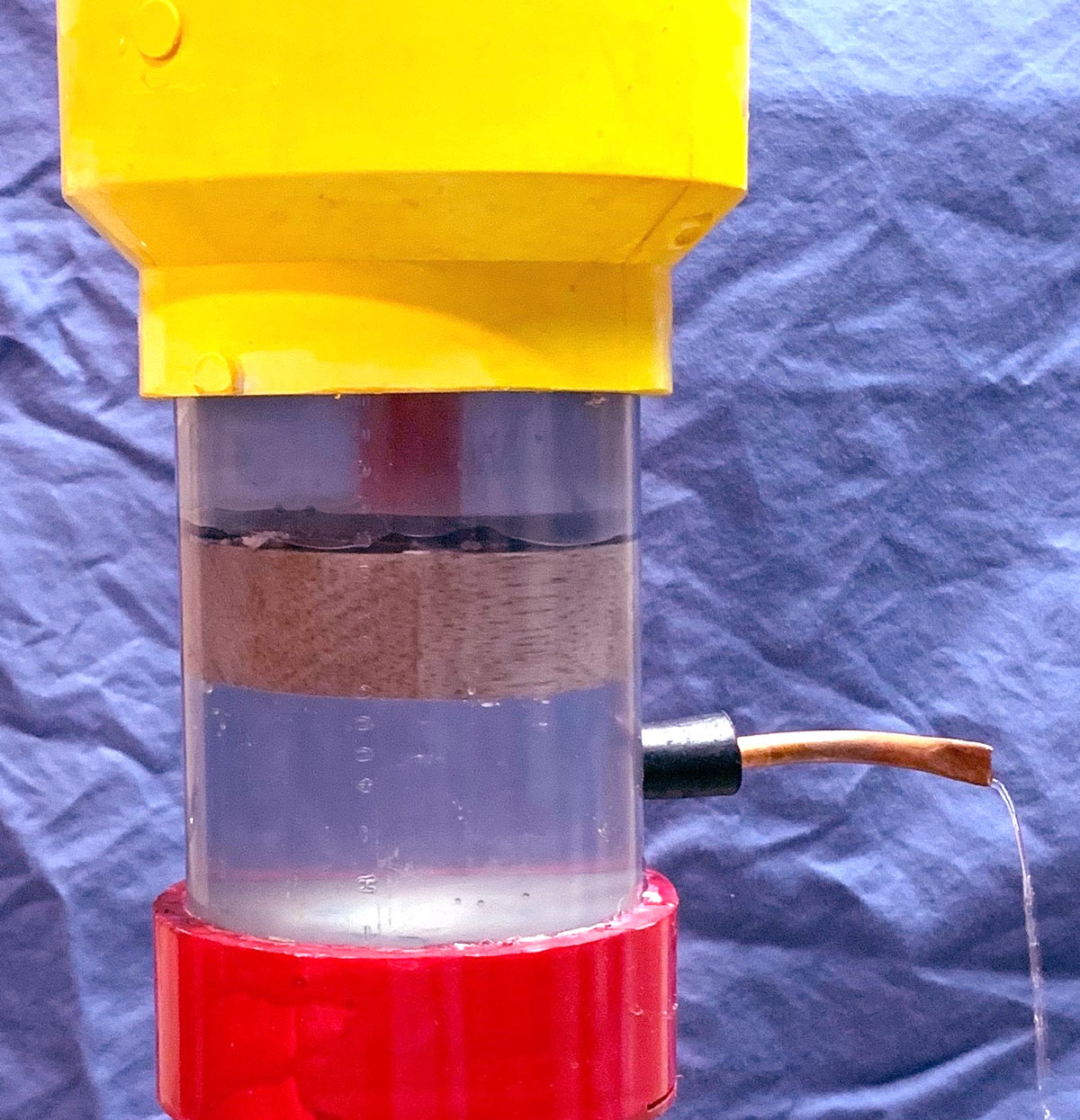

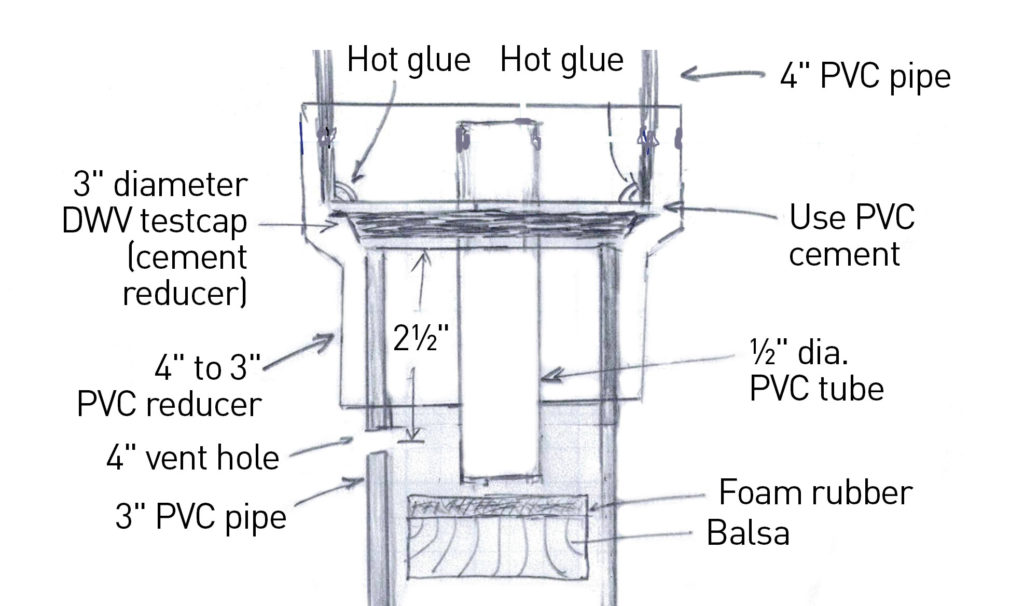

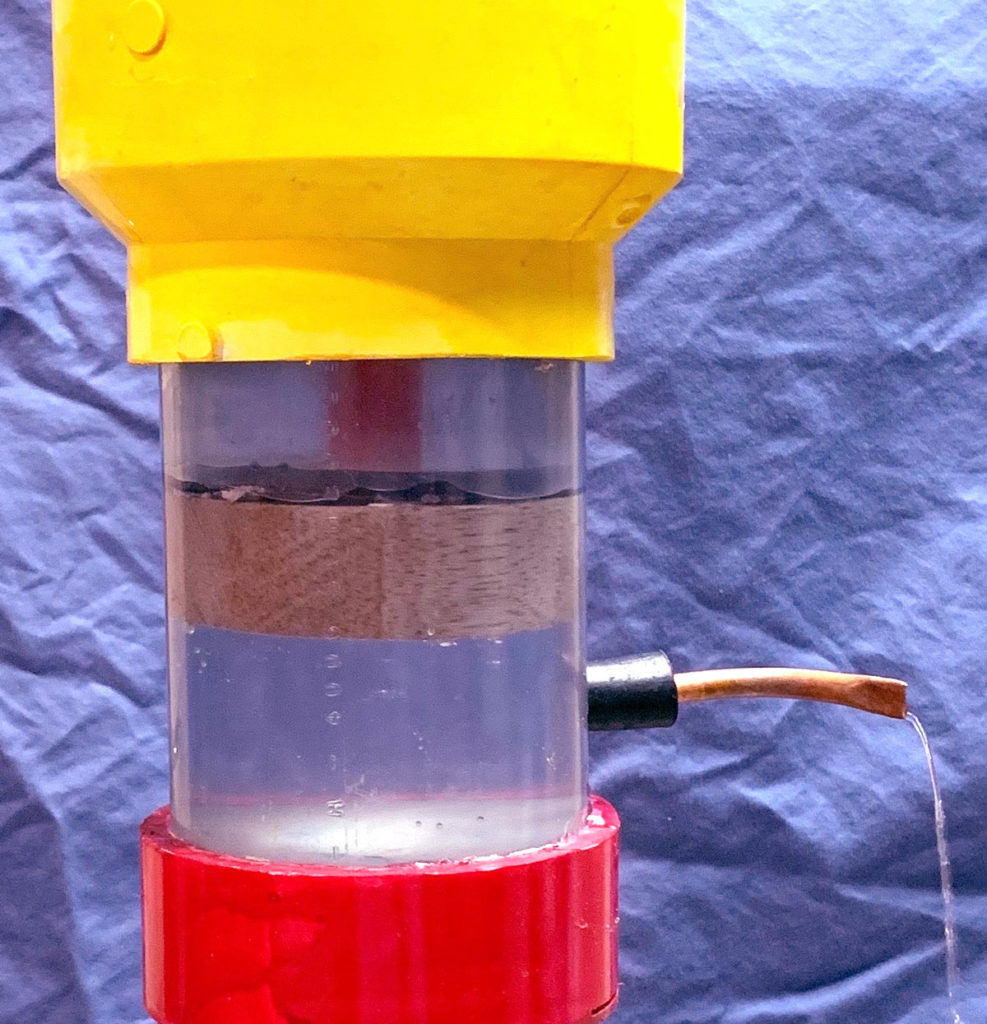

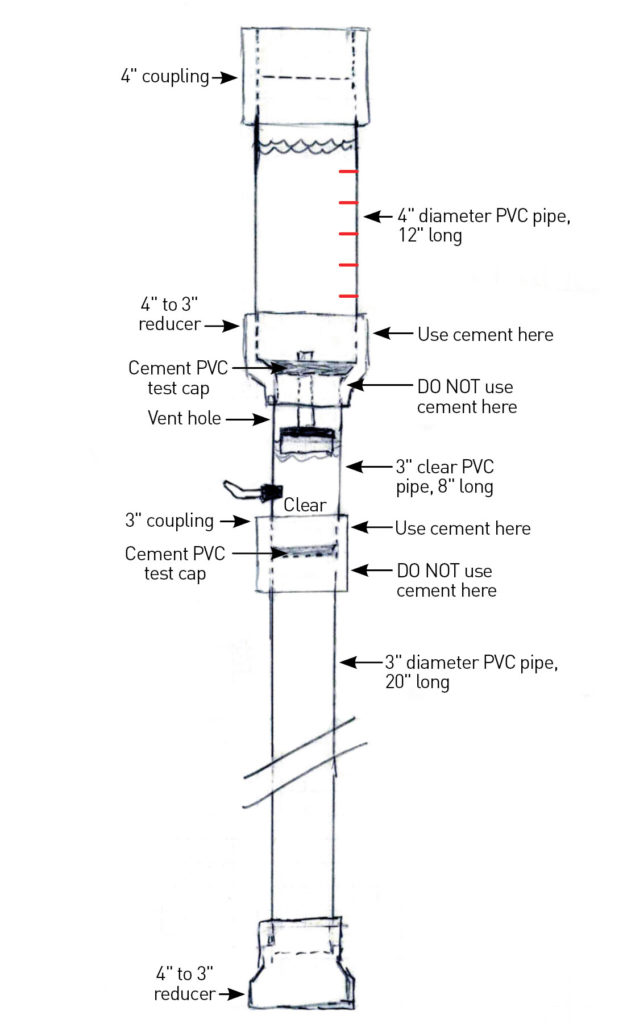

In this issue of Remaking History, we create an al-Jazari-inspired water clock. Like the original, our Elephant Clock has two interesting features that al-Jazari either invented or improved upon (Figure C). The first feature is an automatic float valve that keeps the water level in a tank constant, thus allowing a constant flow rate of water out of the tank. Normally, the rate of water leaving a vessel through a hole in the vessel’s side or bottom slows down as the water level in the tank drops. This phenomenon, known as Torricelli’s Law, is a big problem for water clocks because they indicate the passage of time by showing the difference in the height of water levels from one timing mark to another. Such nonlinear flows make measuring elapsed time very complicated. But with al-Jazari’s automatic valve, the water flow in or out of the measuring tank is always constant.

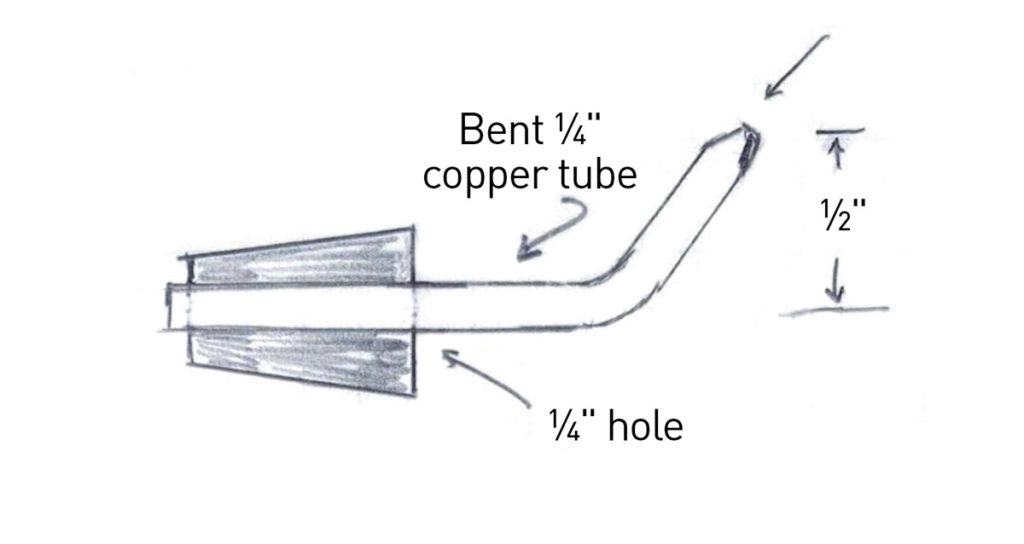

The second interesting feature is the Elephant Clock’s ability to adjust the rate of flow out of the tank. In al-Jazari’s time, the length of an hour was determined by dividing the time between sunup and sundown into 12 equal parts. So, the length of an hour varied greatly by the time of year. Al-Jazari’s Elephant Clock had an adjustable flow spout that could be easily adjusted to run faster or slower by rotating the curved spout to change the clock’s pressure head (the height of the water in the tank above the orifice from which it flows out).

Make Your Al-Jazari-Inspired Water Clock