I love using old machine parts for my projects; often their workmanship surpasses that of anything new, and you can get them cheap or even free. Find a junkyard full of ancient, rusty industrial equipment, and you can build almost anything — or at least be inspired to, which is half the battle!

But many older machine parts, especially cheap ones, have rust, paint, or other coverings that make them ugly and difficult to work with. Over the years, my salvage habit has turned me into something of an expert in amateur metal restoration. I am by no means a metalsmith, but I have collected a library of easy techniques that can enable any moderately equipped hobbyist to clean metal to make it into shiny, working components again.

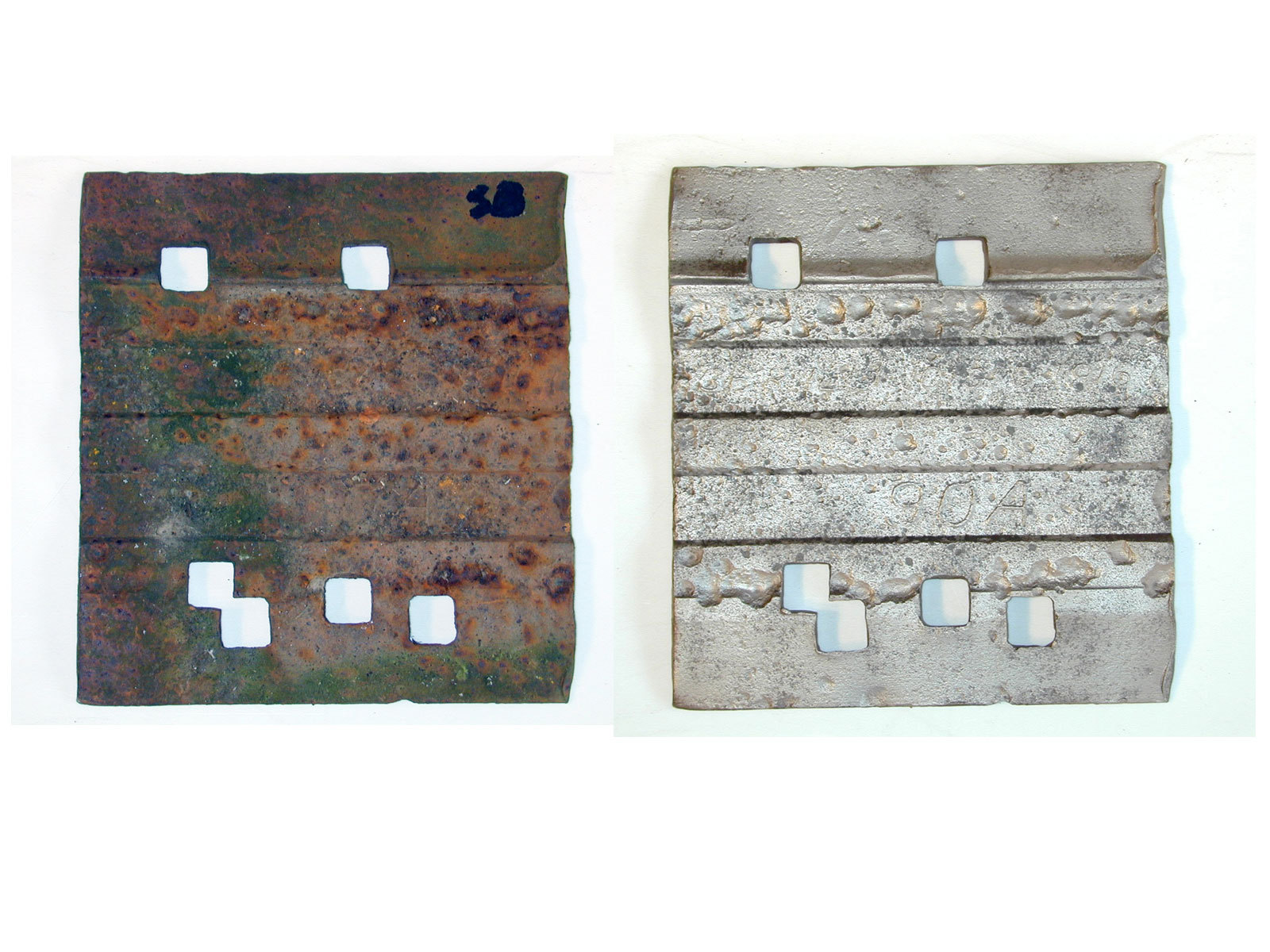

Rust, the oxidation of iron, takes up far more volume than the metal it grows from, so the parts underneath look surprisingly undamaged after treatment. The same goes for old paint, which protects the surfaces underneath it.

There are 3 basic ways to remove oxidation or paint from metal in a home shop: mechanical, chemical, and electrochemical. (Thermal methods, and exotic techniques like dry ice blasting, molten salt dips, and bacterial siderophores, require specialized equipment.) Here I describe some home methods, and how to construct one of the most effective rust-removal tools of all: an electrolytic conversion tank.