With a few hours in the shop, a small amount of wood and just a few tools you can give new life to an old pocket knife.

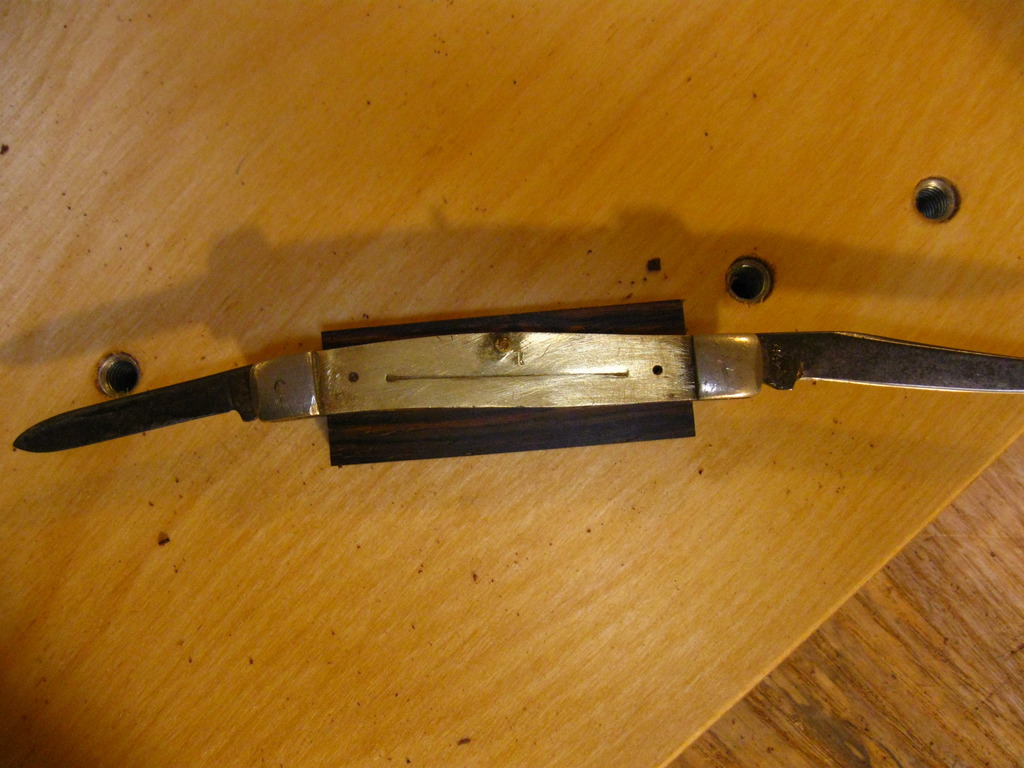

I had an old pen knife that belonged to my grandfather sitting around in a drawer for many years and never really used it because it was in very sorry shape. It was missing one scale and had a roughly-made replacement for the other one, and overall the whole thing was dirty and scuffed up. I finally took this heirloom out to the shop for a proper rehabilitation.

The exact challenges faced will vary from knife to to knife so this guide will aim to describe a general technique instead of an exact step-by-step process. For any knife repair like this you will have to remove the old scale(s), clean and sand the metal parts the new scales will mount on, cut the scale blanks to fit, shape and contour the scales to a close fit, epoxy them into place, shape, sand and buff the whole knife. I did this knife in an afternoon, about five hours.