OK, so you’ve made your project. Whether it’s an original concept of your own or something from a MAKE how-to article — good for you! Maybe you’ve learned a new skill or tried a new tool or process: that’s the fun and reward of making.

But consider your end result. How well does it really work? How does it look? What would make it better? Maybe you’re ready to take your creation to the next level: manufacture and sell. How would a professional maker approach it? That’s a job for an industrial designer!

Industrial design (ID) is the science and art of creating commercial products, experiences, and environments. The skills and techniques the designer uses include ideation sketching, drawing/rendering, drafting, sculpting, and model making. An industrial designer also must know about materials, manufacturing processes, electronics, computer programming, engineering, printing, and graphics.

The industrial designer is the champion of a new product and sees the concept through all the stages: presenting new ideas to management, selling them to marketing, proving the design to engineering, and shepherding the design through the legal and patent processes. The designer needs to consider product safety, cost and ease of manufacture, and package and logo design for print, web, or TV advertisements. In many ways, an industrial designer is a “professional maker.”

History of ID

Since humans began making things, from flint-edged tools to flintlock rifles, we’ve been designing. But in the 20th century, modern manufacturing and mass marketing required a new combination of talents. In the fast-paced, competitive marketplace, only the best-looking, best-working, and most affordable products (and the companies that made them) survived. Manufacturers sought out individuals who had the vision and skills to make the many decisions required in producing a product.

One of the first and most famous industrial designers was Raymond Loewy. An engineer by training, his natural artistic skill and dramatic French flair earned him important commissions. In 1929, Loewy, a true maker and DIYer, hand-sculpted clay in his NYC apartment living room to create a sleek, simplified design for Gestetner’s mimeograph machine. His streamlined designs made things cleaner and easier to use, as well as better selling. Loewy and his firm went on to create or redesign many iconic forms of 20th-century America: the Coca-Cola bottle, the Pennsylvania Railroad S1 locomotive, the Studebaker Avanti, Air Force One, and many others. He famously said, “The most beautiful curve is a rising sales graph.”

In the second half of the 20th century, husband-and-wife team Charles and Ray Eames expanded the field of industrial design to include not just products, but also exhibits (IBM at the World’s Fair) and educational films (Powers of Ten). Together, they created handsome chairs and furnishings for homes and offices. Also very hands-on, the Eames assembled their own electrically heated and bicycle pump-pressurized molding machine, nicknamed the “Kazam!” They used it in their Los Angeles apartment to bend flat pieces of plywood into three-dimensional shapes, creating splints and litters for the U.S. Navy. The classic Eames chair is the direct descendent of their early experiments. Their application of both science and art produced tasteful and elegant designs that connected with consumers emotionally and continue to sell and inspire designers 50 years later.

Today, industrial designers like Jonathan Ive (Apple iMac, iPad) or Yves Behar (XO laptop) have access to advanced technologies like Cintiq tablets, SolidWorks, and rapid prototyping fabrication, but the basic approach to designing a new product is the same. As an exercise, let’s take a sample MAKE project and see how the creative process used by an industrial designer might improve it.

The ID Creative Process

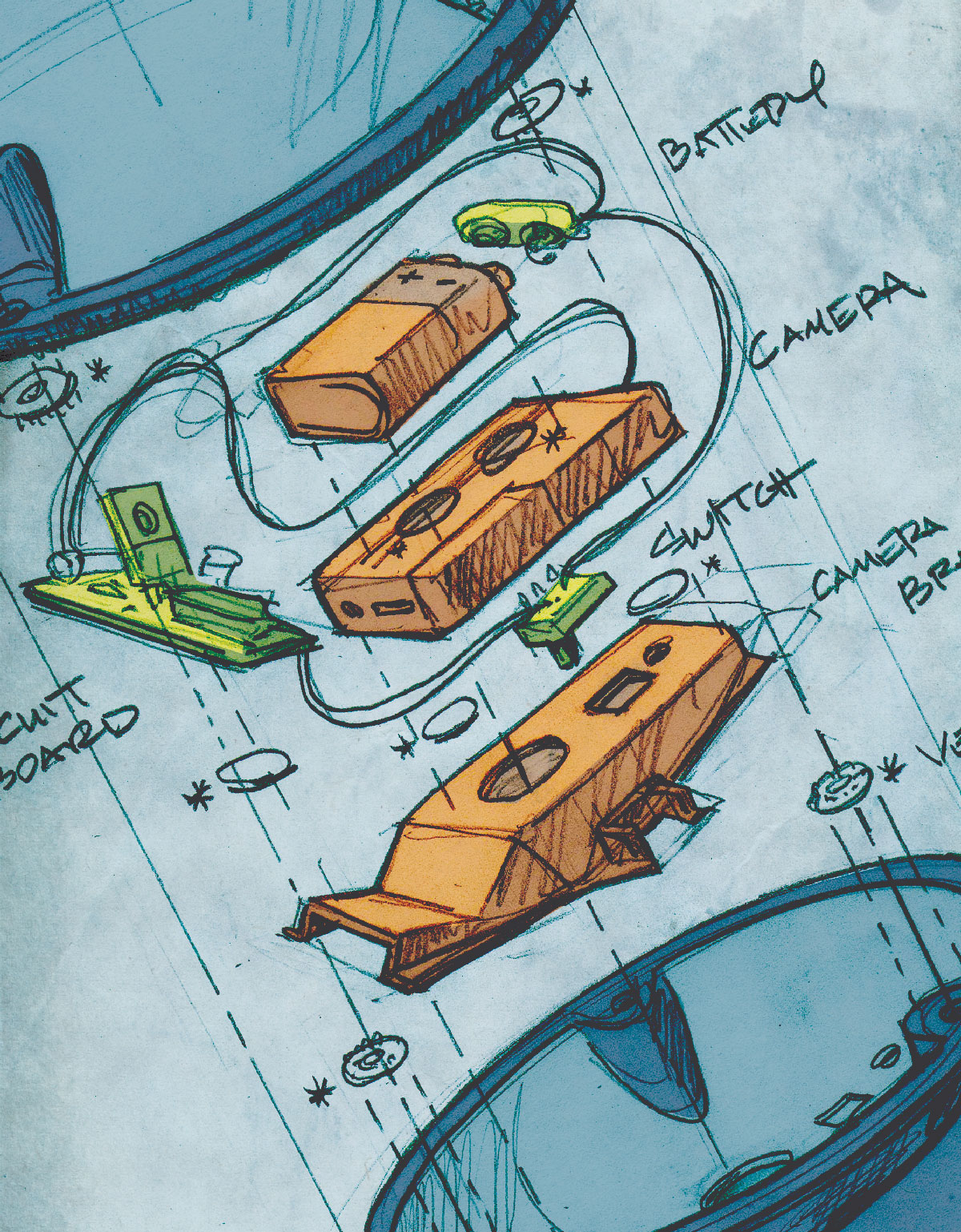

The Helium Balloon Imaging “Satellite” camera from MAKE Volume 24 is Jim Newell’s clever hack made by adding a timer circuit to the shutter button of an inexpensive camera, then sent aloft by tethered helium balloons to take aerial photographs. It’s made of repurposed items: a CD serves as a platform to hold the camera, a prescription bottle contains the circuit and battery, and it’s all held together by twists of wire. It looks as if it were thrown together from items scavenged from the trash bin: MacGyver-worthy, but not a very elegant design.

It’s also not very easy to use: you have to remove the camera (it’s fastened to the CD with double-sided tape), turn it on, replace the camera, connect the circuit board, attach the battery that starts the timer, reconnect the cap (and don’t let the balloons get away while you’re doing all this!), let out the string to fly the balloon, taking pictures as it goes up. It’s begging for a redesign.

For the purpose of this article, let’s assume there’s a client who wants to manufacture and sell the Balloon Cam as a DIY kit and is working with an industrial designer to help refine the design. The design process includes these steps:

- Define scope

- Ideate

- Review

- Develop prototype

- Test and revise