In 1764, scotsman James Watt grew thoughtful as he tinkered with the machinery associated with his job as a steam engine technician. The main problem with those early steam engines, called Newcomen engines, was that they were terribly inefficient. They were a step up from draft horses, but Newcomen engines went through coal like a starving man on a Christmas ham.

This inefficiency, thought Watt, was simply unacceptable, and he believed he could do better. When Watt put his mind to a task, he was a nearly unstoppable force. Besides his preternatural drive and determination, he possessed, as English historian Samuel Smiles said, “a keen eye for details, with which he combined a comprehensive grasp of intellect.” In fairly short order, Watt made radical improvements to the early steam engines, boosting their efficiency and utility. Those improved Watt engines changed the world, leading to the Industrial Revolution in England, America, and beyond.

But Watt wasn’t finished yet. One of the many engine-related inventions for which Watt is credited is the flyball or centrifugal governor. In the early days of the Industrial Revolution, most engine operators in mills and mines needed to keep their machines turning at a constant rate of speed, irrespective of the load placed on them. Generally the speed of an engine increases when the load decreases, so, for example, if a pump removing water from a mine shaft needed to operate at 70rpm, then the operator had to manually open or close the steam valve whenever the amount of water in the mine shaft changed.

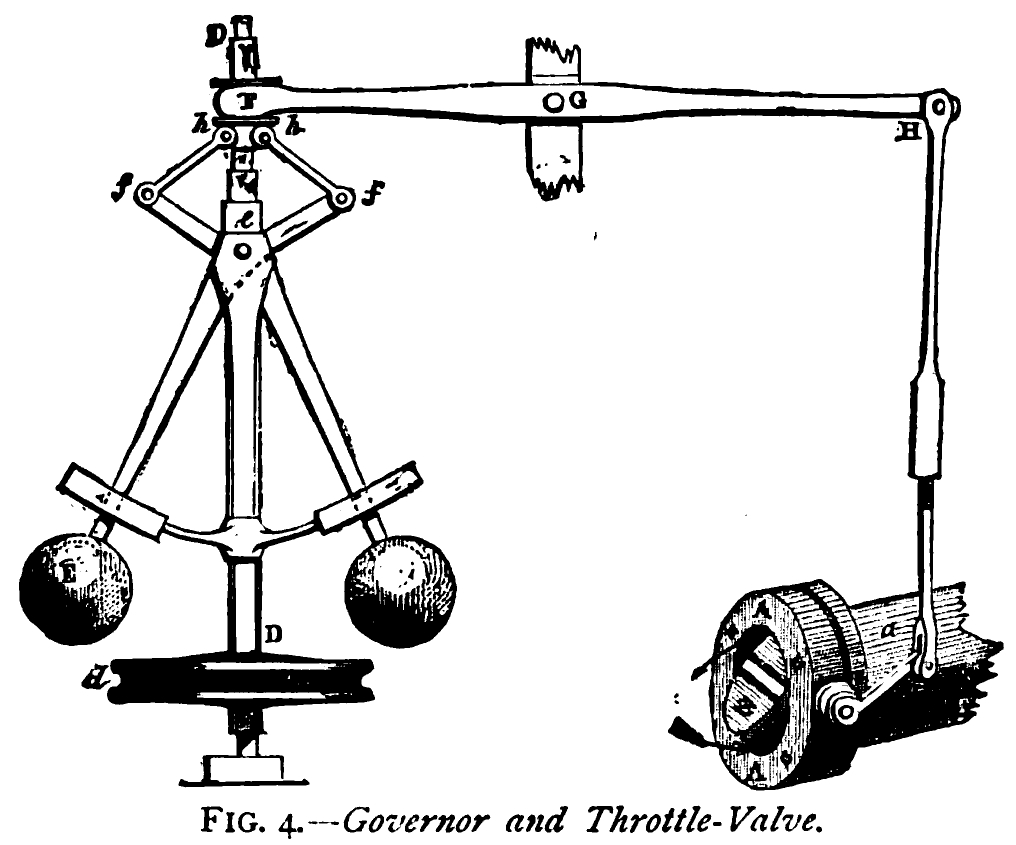

In 1788, Watt began to think about a way to make this happen automatically. His solution was the flyball governor. The flyball governor is based on the idea of a feedback control loop. It works like this: Weighted balls are linked via hinged arms to the shaft of a steam engine. As the engine turns faster, the hinged flyballs fly apart. But, as the balls separate, a linkage causes the throttle on the steam engine to close.

Less steam means the engine slows down and the flyballs come back together. But, when they get too close to one another, the linkage causes the throttle to reopen and the engine speeds up again, and thus an endless loop of engine speed adjustment ensues. If designed well, the flyball governor maintains a fairly constant engine speed, no matter what the load.

While Watt didn’t originate the concept of the centrifugal governor (Christiaan Huygens invented one for clocks, see “Poetry in Motion,” page 40) or the feedback loop, his is one of the first important examples of the idea in use in large machines.

In this edition of Remaking History, we make a James Watt-style flyball governor. Since few of us have steam valves and boilers readily available for a project, we’ll use the electricity from a couple 9-volt batteries in place of the boiler, and a pair of aluminum brushes instead of a steam valve. This simplified, on-off rendition of Watt’s world-changing wonder is cheap to build, fairly easy to make, and great fun to show off to friends and family.

Build an Electrica Flyball Governor

There are four main components of this flyball governor project: the shaft, the base, the flyball linkage, and the control brushes.