The engines of the Industrial Revolution that ran the machinery in the early textile mills, turned the screws of steamships, and powered the drive wheels of locomotives were made of iron and powered by coal. At the beginning, both the iron ore and the coal came from mines located in England. Mining was hard work, and one of the many difficulties associated with mining was the seeping water that constantly flooded the mines. “Dewatering” was a necessity in nearly all mines, and still is today.

In 1698, Thomas Savery came up with an idea for solving this problem. Savery was a former military engineer from a tin- and copper-mining county in southwest England. His military rank was “trench master,” meaning he was in charge of building underground constructions. He must have been skilled at it because he rose to the title of Captain Savery.

After leaving the military, Savery continued to think about life below ground, and he judged the old ways of pumping water inadequate. “For more than an hundred years,” he wrote in 1702, “men and horses would raise … as much water as they have ever done, or I believe ever will.” He had long thought about ways to remove water from places underground, and he had “happily found a new and much stronger and cheaper force for powering pumps.” That force, he explained, was fire.

In retrospect, Savery’s invention, which he christened “the Miner’s Friend,” was more than just a pump. It was in fact the first machine that used the energy within fossil fuels to do useful work on an industrial scale. The Miner’s Friend was neither efficient nor elegant, but it was important. With it, Savery unhitched industry from the limitations of animal, wind, and water power.

Savery’s machine consisted of a large, sealed iron tank. The tank was filled with steam, piped in from a large boiler. The machine operator closed the steam valve and then sprayed the outside of the tank with cool water. That caused the steam inside to condense back into water. Since liquid water occupies only a small fraction of the volume of steam, a strong vacuum was created inside the tank. The tank, connected by another pipe controlled by two check valves to the mine water that needed to be pumped out, drew up the water. When the tank was full of water, the steam valve was reopened and the steam forced the water out of the tank, out the pipe, and out of the mine. The process was repeated over and over

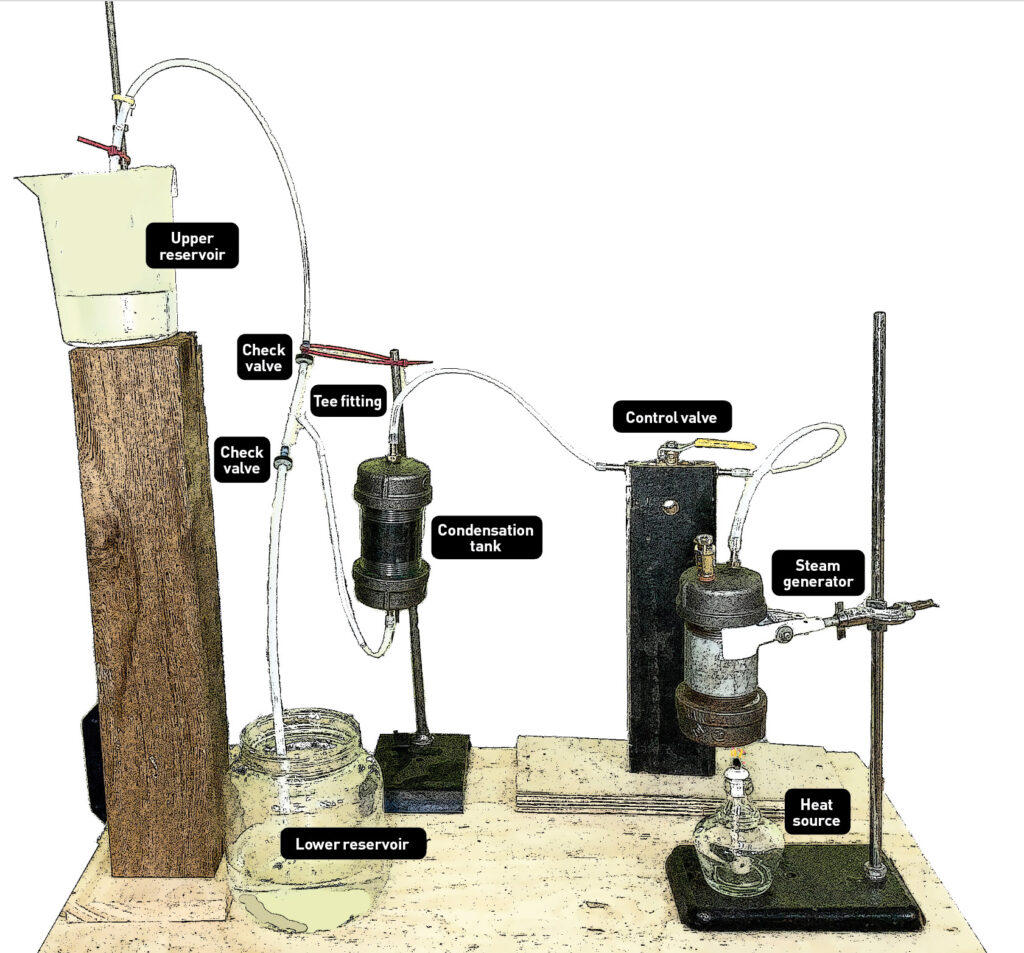

In this Remaking History column, we will build a model of Savery’s Miner’s Friend. Although it was a cumbersome and inefficient machine — today it’s remembered mostly as the precursor to the far more successful Newcomen and Watt steam engines (which had pistons) — it is fun to observe in action and teaches important historical and engineering lessons.

Note carefully that it is a steam-operated machine. Steam, if not given respect, can be dangerous. As always with DIY projects of this nature, proceed at your own risk.

CAUTION: Safety With Steam

You are working with steam which is inherently dangerous. If the tubing breaks or comes loose, the escaping steam can cause scalds. Wear gloves, heavy clothing, and face protection when building or operating the Miner’s Friend.

I used iron pipe and fittings, and an adjustable pressure relief valve for a makeshift steam generator. I had no problem with this setup, but a better, safer, and more expensive solution would be to buy a model steam engine boiler to serve as a steam generator.

- Install a 15psi (or less) pressure relief valve and a sight glass on the steam generator. The sight glass allows you to check water levels inside the steam generator. Never let the steam generator run dry.

- There is no piston in the Miner’s Friend, and thus no need for pressurized steam. Therefore, leave the control valve open at all times except when actually pumping water and even then, never leave the control valve closed for more than 5 to 10 seconds.

- Make certain the check valves are oriented correctly.

- The tube from the condensing tank to the upper reservoir must be open to the atmosphere at all times, so always keep the tube’s opening above the waterline in the upper reservoir. To do so, use clamps to keep the components in position. Further, be sure that there are no kinks in the tubing, and that the hose barbs on the fittings are fully inserted into the tube.

- All “hot side” components (tubing, valves, and fittings between the inlet of the condensation tank and the steam generator) must have an upper working limit of at least 250°F.

- Use pipe compound on all pipe threads to prevent leaks.