There are a handful of twitter profiles I rely on to open my mind every day. One of them is @CorinneTakara, an artist and teacher based in San Jose, CA where she does her studio work and runs a makerspace out of her garage called, aptly, The Nest, focused on design, biology, and engineering.

Currently, she’s supporting a group of teens in the annual Biodesign Challenge showcasing future applications of biotechnology.

The Nest team explores expressive, sustainable design with cellular materials such as mycelium (the lacy, white vegetative root structure that supports the growth of mushrooms) and bioplastics using agar, derived from seaweed, and chitin, a material used in dissolvable surgical thread that’s found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects, and in outer sheaths of the mycelium fungus.

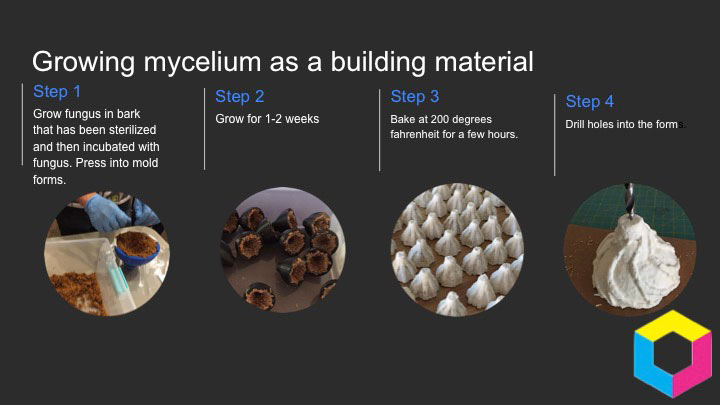

The team conducts many of its projects as a set “recipes.” They grow and cure a substrate compound using “mycelium seeded bark” to fashion objects such as lampshades, containers, and other forms; they create unique castings and press-molded projects with bio plastics; they culture kombucha, the fermented tea drink, to develop a “scoby,” the rubbery layer of yeast and bacteria that can be dried, then crafted as a project material.

Part science lab, part artistic experiment, part eye-opening experience with the natural world, these GIY (grow-it-yourself) projects focus deeply on nature, its processes and characteristics, and our ability to construct things with organic materials.

For more context, I reached out to Tito Jankowski, one of the co-founders of the original biohacking space, BioCurious; he runs Impossible Labs, a consultancy focused on climate, and serves as an advisor for Corinne’s high school students and their work on the Biodesign Challenge.

Tito described the backdrop for these explorations of natural material as an emergent offshoot of the revolutionary research done on the human genome project, which, in addition to launching the genomics revolution, introduced the transformative discipline known as Synthetic Biology, or SynBio, combining biology, chemistry, and computation.

He talked about companies such as Materiom, Ecovative, Bolt Threads, and Memphis Meats, commenting that projects like these are going to re-shape industrial materials, grow renewable sourcing for clothing, and provide new food sources and cellular protein.

“What’s common across these projects,” Tito said, “and what ties in directly with the Nest team, is the focus on sustainability and an ambition to use biological material to reduce our carbon footprint and support better ways to live, work, and collaborate.”

Corinne is developing the work at the Nest makerspace iteratively, through small group work and applied, artistic experimentation, showing us how to use natural materials to create organic (no pun intended) and evocative projects that have specific and personal applications.

Makerspace coordinators and curious hands-on learners everywhere who want get some dirt, maybe some mycelium, under your fingernails, please take notice.

You are just getting back from the Fablearn conference at Teachers College and Columbia University in NYC where you and a student team you’re working with presented their “Living Leather Project” — can you share some details on this work?

Yes! I am working with a small team of teen girls who are exploring creating a toy kit that others can grow and share. The team envisions a kit experience that introduces bacterial cellulose and mycelium as sustainable materials to grow and build play experiences from. For example, they designed small 3D printed wings (shared on Tinkercad) that can be skinned with bacterial cellulose and snapped to Legos. They are also designing vacuum formed flower pot creature molds to grow mycelium in. A waste stream substrate such as coffee grounds or plant cuttings is incubated with mycelium and pressed into these molds to grow the forms. They are also thinking about process and how to build culture fails into the play experience. For example, they have designed a petri dish kaleidoscope that one can put scraps of substrate and failed culture growths into. They are also imagining an “open when fails” envelope with fun ideas for extended play with failed material growths. Here is their project website that they are slowly fleshing out.

If we can learn about a maker from the materials and tools she chooses, what can we learn about you from this palette: mycelium, silkworms, mealworms, algae, chitin and kombucha?

Maybe it highlights my curiosity for a slower approach to making and my love of nature in all its forms. It also highlights my desire to find accessible entry points to engaging people in conversations centered on biomaterials and sustainability design. I wanted to explore materials that are low cost, relatively easy to grown, easy to dispose of, and break down the fear factor. Humble organisms in often overlooked corners of nature may be key to deep innovation in sustainable design, but the general public has a fear of many of these organisms. I think it is important to break down these fears with creative craft activities that give the public hands on experience with grown biomaterials so that they, too, can start imagining applications for these materials in their world.

“Grow It Yourself” projects introduce an implicit focus on materials that have a relationship to the natural world. A clear extension of this idea comes in the ways that local communities and cultures put these materials to use. Can you talk about this aspect of the work and your interest in this approach to materials?

In my youth workshops in various communities, I see a pretty profound student illiteracy in the natural world around them. Students don’t know the names of the plants in front of their schools, or the names of the veins of water that lace their communities under or above ground. A great way to connect youth to nature is through culture, their own and others. My dad spent his early childhood on a Maui plantation and the community creatively repurposed both manmade materials and natural materials consumed from their environment. Their creative thriftiness blended rural traditional Japanese practices with the innovative practices of other cultures on the plantations. This thoughtful use of materials has inspired both my workshops and my fine art, which is often a patchwork of artifact from plantation era Hawaii blended with modern day artifacts.

As we bring in locally sourced materials into our maker experiences and as we look to natural building materials, we will also need to look at a broader range of traditional cultural practices for inspiration. Casting the net wider for deeper innovation paths with biology will give us opportunities to engage students through their own cultural traditions and historical practices.

I love to show students a slide of a Cameroon musgum dwelling next to the four finalists of a recent NASA Mars 3D printed habitat challenge. The modern designs clearly drew inspiration from humanity’s past knowledge of building from on-site materials. The musgum dwelling looks like it is one of the design finalists. The form of a musgum dwelling has the best load bearing properties for a self supporting soil structure. The patterned veins in the facade are not just decorative, but help guide the flow of rain. The rain flow accentuates the pattern, rather than collapsing the structure. So in addition to fungus, bacteria and worms, I think we also need to add mud into our makerspaces. We need to be looking backwards as well as forward.

From your current focus on cellular materials and design to your personal artworks and commissions, there’s a wonderful use of collage, man-made and natural materials, traditional forms — like a kimono, say — and a keen, playful sense for how to engage the public in your process and your artworks. Can you talk about the “dialogue” that unfolds between yourself as an artist, a maker, a community member?

I am so glad you observed these themes across my work. Often I am sparked by conversations centered on place and identity, whether I am using bio materials or scraps of Asian food wrappers. Since much of my art exploration is grant funded, I am able to develop public participatory workshops that engage people with the materials I use in my work and we can tinker together. In our rapidly shifting neighborhoods, I believe we need to be in constant conversation to build deeper a sense of community and art can be a part of that dialog. Artifacts from our varied pasts, present, and artifacts which we grow can anchor us to place through the stories that emerge when when combine them in new ways. I find this recombination so exciting. This collaging can illuminate a sense of personal and collective identity which is both familiar and surprising. Though this dialog in art, we can share stories of where we came from and hint at where we are going.

As an educator, workshop leader, mentor and coach, you’re constantly imagining experiences that can introduce prompts or provocations in ways that will lead participants in new directions — ideally in ways that increase confidence and curiosity.

How you design workshop activities? For example, you’ve commented that the “How might we” prompt has been especially effective at inviting girls into complex conversations about design and purpose.

When I design a workshop activity, I frame it as a conversation starter that I hope carries over into people’s discussions at home. The best way to get people engaged in expressing themselves is to keep things open-ended and to let them know that there is no one correct artifact outcome to an activity. Often, I am barely ahead of participants on the learning curve with a technology or medium that is used in a workshop. This creates a truly collaborative environment as we, together, are exploring answers and approaches to a question and a medium. Public pop-up experiences that engage a greater diversity of people in conversations of “How might we?” can give people confidence to look at their own creativity as part of their community’s problem solving tool kit.

In regards to the [Biodesign Challenge] team, so much of what they are doing I have never done or even prototyped out before. So the questions I ask are ones they have to hunt down and we have to research and reach out to others for clarification and direction. We have been very fortunate in having many Skype discussion with wonderful experts willing to talk with the girls (like Keegan Kirkpatrick, CEO of Redworks; Dr. Lynn Rothschild of NASA Ames Myco-Architecture Program; Liam Nilsen, Learning Experience Designer at Lego, Denmark; and, of course, Tito Jankowski, Co-Founder and CEO of Impossible Labs).

Often as they are figuring out how to tackle a workshop project, the girls each experiment with a different approach, and then discuss and combine the best direction based on their collective explorations. They know they are not going to receive a prescriptive step-by-step lesson from me, and I think this builds their curiosity and collaboration skills. They share out loud what they discover during the process of what they are doing as they are inventing the process as they go. When the outcome of an exploration is not what they want or what they expect, they discuss and decide where to pivot. Moments of failure are not failures, but spots where they identified a new direction to move into.

Let’s close with some more details on the Biodesign Challenge and your work with Tito. The challenge encapsulates so many important ideas — from equity in STEM to imagining sustainable futures. What can you share about the team’s progress so far and the example this work is offering for teens and high school students?

This year the challenge opened up to high schools. There is a need for biodesign journeys for young adult learners since solutions to our pressing environmental issues will depend upon deep innovation through blended explorations across disciplines.

Teen groups exploring these issues from an art/design angle can create a point of entry for biodesign conversations with a larger public and younger ages.

The team is asking themselves this question: how might we develop playful and engaging biomaterial design experiences that make sustainability topics fun, exploratory, and expand people’s sense of agency and deep connection to the nature around them?

After focusing initially on three categories (fashion, food and play), my Nest Makerspace team narrowed their focus to play and with the goal of developing a grow-it-yourself toy kit, GIY BioBuddies.

They aim to create low cost, flexible, and playful introductions to growing and using biomaterials. They want their kit to provide accessible, play-based points of entry on these experiences using locally sourced natural materials as well as waste stream materials.

Tito has been a great mentor and challenged them to think about a few key things when working with the biological materials they have chosen. Given the short material lifespan of kombucha leather, how might you design for that planned obsolescence? How might one tap into local wastes streams as feedstock for the kits? He advised them to make instructions fun and simple and perhaps number tools with stickers that match numbers in instructions.

Along the way, they have been growing bacterial cellulose, pressing mycelium inclubated substrates into mold forms, exploring 3D printing, vacuum forming, collecting natural materials from parks, and are envisioning the potential for a biomaterial incubator that houses drying racks and has a cooking timer that displays days and weeks, rather than hours and minutes.

One aspect that the Biodesign Challenge highlights is testing ideas and involving the target user groups along the path of idea development. With this in mind, the team is doing a lot of surveys and workshops to build their knowledge.

IMAGE: Kombucha.Leather.Lights.Project.jpg

Caption: Steps in the Kombucha Light Project. Drying, Design, Final Assembly. Photos courtesy of Corinne Okada Takara

Next month, on the 28th of April, the Tech Museum of Innovation is opening up their Biotinkering Lab to the team so they can conduct their kombucha leather activities: petri dish kaleidoscope, Lego compatible kombucha leather wings, and kombucha leather paper dolls. On April 13th at the Cupertino Earth & Arbor Day Festival, the team will test their mycelium creature planters activity – children will build their creature mixing and matching bases of grown mycelium forms and adding local natural materials to decorate them. The final touch is to plant a sprout in the container.

These planters are grown in vacuum form molds the girls made from recycled milk jugs using vacuum forming based on 3D printed designs they created in Tinkercad. If time allows, they may conduct a kombucha leather activity at the AYA Makerspace in East San Jose. All these workshops will help them refine their activities and inform the design and look and feel of their kit system.

Reading List

For more background on Corinne’s work, her studio projects, maker workshops, collaborations, and some examples of companies exploring biological materials, see the links below.

Okada Design; @CorinneTakara; the #biotinkering hashtag; the BioChallenge website; the NEST Makerspace weebly; the GIYBiobuddies website; and the deck Corinne shared at the recent Fablearn Conference at Teachers College.

Don’t miss the Nest Makerspace Biodesign Challenge Syllabus 2018-2019 — it’s an excellent resource for thinking about introductory teaching and learning in the emerging field of natural materials and design.

Curious about the Mud Dwellings of the Musgum Tribe in Cameroon?

For more on the industry examples mentioned: @materiom, @ecovative, @bolthreads, @memphismeats

ADVERTISEMENT