When Bill Kennedy saw a Facebook post seeking someone to work on an inflatable art car, he replied that he had relevant Burning Man experience earning him the nickname “Inflatabill,” which became the name of his own business. By December 2020, Inflatabill’s event business had dropped off because of Covid and he was worried about paying the rent on his Santa Rosa, California, workshop. Knowing he needed the work, he drove down to San Rafael and walked into an old airplane hangar. There he saw the project that would occupy him for the next 20 months.

A project manager met Bill and showed him a strange, 23-foot vehicle: a modified Polaris General side-by-side ATV chassis with a trailer. It was the skeleton of an unfinished art car that was conceived to be an illuminated cuttlefish, the so-called “chameleon of the sea” because its body changes color. To bring the cuttlefish to life, the car would need inflatable fins that could move up and down in a wave motion along both sides of its body, and they would need to control the brightness and color mix of the lighting. The head of this cuttlefish would have two prominent eyes and eight or 10 arms.

What Bill saw in the hangar that day was bare bones. The fins were two sets of poles wrapped in pool noodles and attached to cams that would move them up and down. The inflatables, which would fit over the pool noodles, would be lit with LED strips. The project manager explained that the person who designed an inflatable skin for the car couldn’t get it to fit. She asked if Bill could sew the existing fabric in place, but Bill said he’d have to redesign the skin — and much more.

Bill learned to work with fabric and sew as a certified parachute rigger. “I was a skydive bum and it’s expensive,” he said. “To pay for it, I learned to pack and repair parachutes.” It was regular work that could be found nearly anywhere in the world, and it funded his avocation. Later he apprenticed for a man who showed him how to design, cut, and sew inflatables by hand, before he established his own business. In the late 1990s, Bill went to his first Burning Man and eventually began working on art cars. He fabricated the large dirigible as an inflatable for the Airpusher Art Car.

An unfinished art car

Looking at the cuttlefish skeleton, Bill was told that the build team was gone. “They were a disparate group that was brought in for a particular task and when that task was done, they moved on,” said Bill. “That’s not how most of the Burning Man art cars are built.” None of that team had ever been to Burning Man and they didn’t understand what the vehicle would have to endure. “It’s a harsh environment that destroys everything,” said Bill. “Everything breaks.” The art car was built for a patron who interacted only with the project manager, not the builders, and who wanted to ride it around Burning Man.

Photo by Brian Willison

As Bill did his walkaround, he wasn’t sure what to say. “They had already spent so much money on the project and they had a failed car,” said Bill. There was a sticker for an approved art car for Burning Man 2020, but that event was canceled because of COVID. The car wouldn’t have made it there anyway.

When Bill came back from that visit, he told Brian Willison, who shares his workshop, about what he saw. “This thing’s cool,” he told him.

Brian, who is a lighting designer, has worked with Bill on many projects for festivals over the years. He joined him on a trip to the hangar. “I walked in and there’s this thing sitting there,” said Brian. “Of course, I instantly go to the lighting.”

He didn’t like what he saw. “I see round lights, what are called a PAR because they resemble an old PAR can from the 80s,” he said. “They’re round fixtures that now use LEDs. They’re okay but not very bright, especially for the desert. I see the pool noodles with LED light strips wrapped around them.” The wiring was a rat’s nest of cables, and the controller box was hard to access. Inside, he was surprised to find a proprietary, custom-built lighting controller — not a choice he would have made.

A new team takes over

Two people with complementary skill sets, one more artistic in temperament and the other more technical and curious, but both perfectionists, Bill took on the design of the inflatable skin and Brian the lighting system for the fins and tentacles. They began making regular visits to the hangar together.

“Originally we were under the impression everything was working,” said Brian. But they quickly ran into problems with the work the first team had done. “We kept finding so many things they overlooked,” said Bill, so the pair ended up stripping the car. “We took all the cables, all the components, all the batteries, everything off the car,” said Brian.

Photo by Brian Willison

On one visit, they found the hangar flooded. Bill convinced the project manager that they should move the art car to his Santa Rosa shop. However, the vehicle was 6 inches too wide for legal transport on the road. Bill wondered aloud why the first team hadn’t thought to check that out. “Were they going to haul it to Burning Man as a wide load?” They found a driver to haul it to Santa Rosa on the back of a flatbed truck.

“I learned that the project manager was a sculptor who conceived the project and made a maquette of the cuttlefish,” said Bill. “Another guy did a CAD design for it but he told me that they didn’t really follow the CAD design closely, and when they made changes they didn’t update the CAD model.” Bill had to start over and get accurate measurements for the inflatable skin.

As they began measuring the art car, they found that it was not symmetrical. It was like taking over a kitchen remodel from another builder and finding out that the framing was not square, the plumbing fixtures were unusual, and the appliances wouldn’t fit in the cabinet openings.

“We just wanted to do what was best for the client,” said Brian. “And it certainly felt bad undoing someone’s work. But it wasn’t ready and it wasn’t ever going to work.” The good side was they had a lot of creative freedom. “There was a frame and a chassis and a trailer that weren’t going to change, but the length of the fins, the length of the tentacles, all of that was up for us to decide.”

Their goal was to be ready for Burning Man 2021, but that was also canceled because of COVID. “That gave us a bit of breathing room,” said Brian, “to make bigger, major changes that needed to happen.”

As Brian took on more project management duties, a third member joined the project in the late summer of 2021. Brian knew that Loren Crotty was looking for work. “I also knew that he has a background in batteries and electric motorcycles. He’s also a pretty good fabricator and welder.” Loren just did odd jobs at first, but eventually he would take over the project.

The shape of balloons

To build an accurate CAD model of the cuttlefish from scratch, Bill used photogrammetry, taking pictures one at a time with his phone and using them as the basis of the 3D model. He also got a CAD file for the Polaris ATV and merged the two.

Having used many CAD systems over the years, from the early versions of AutoCAD on, Bill now works in Rhino with specialized plug-ins. “I use CAD to unfold curved surfaces,” he said. “A lot of the technology I use comes from sailmaking. Most people don’t realize that sails are not actually flat, but curved. The first flattening software that I used was made for boat builders.” Unfolding, he explained, “is taking a curved 3D surface and flattening it down into multiple 2D slices, similar to the way a 3D beach ball is made from a series of flat 2D segments. In the old days, we would start with a clay model, dip it in latex, and slice that latex skin into lots of pieces that we would then literally squish flat and trace to make paper patterns. Now I do it all with software.

“After building a 3D model, I use ExactFlat to slice and flatten the mesh into 2D DXF files. I bring those files into PatternSmith to add seam allowances and alignment notches, and then arrange all the pieces on a virtual cutting table. Once everything looks good, I unroll the fabric onto the 14-foot Autometrix cutting table which uses a vacuum, like a reverse air hockey table, to suck the fabric flat to the surface before a CNC rolling blade cuts out all the pieces. It’s then just a matter of sewing all those pieces” — 911 pieces, in the case of the cuttlefish — “together like a giant 3D jigsaw puzzle, and adding air to make it a balloon.” Bill refers to himself as a high-tech balloon maker.

Photo by Bill Kennedy

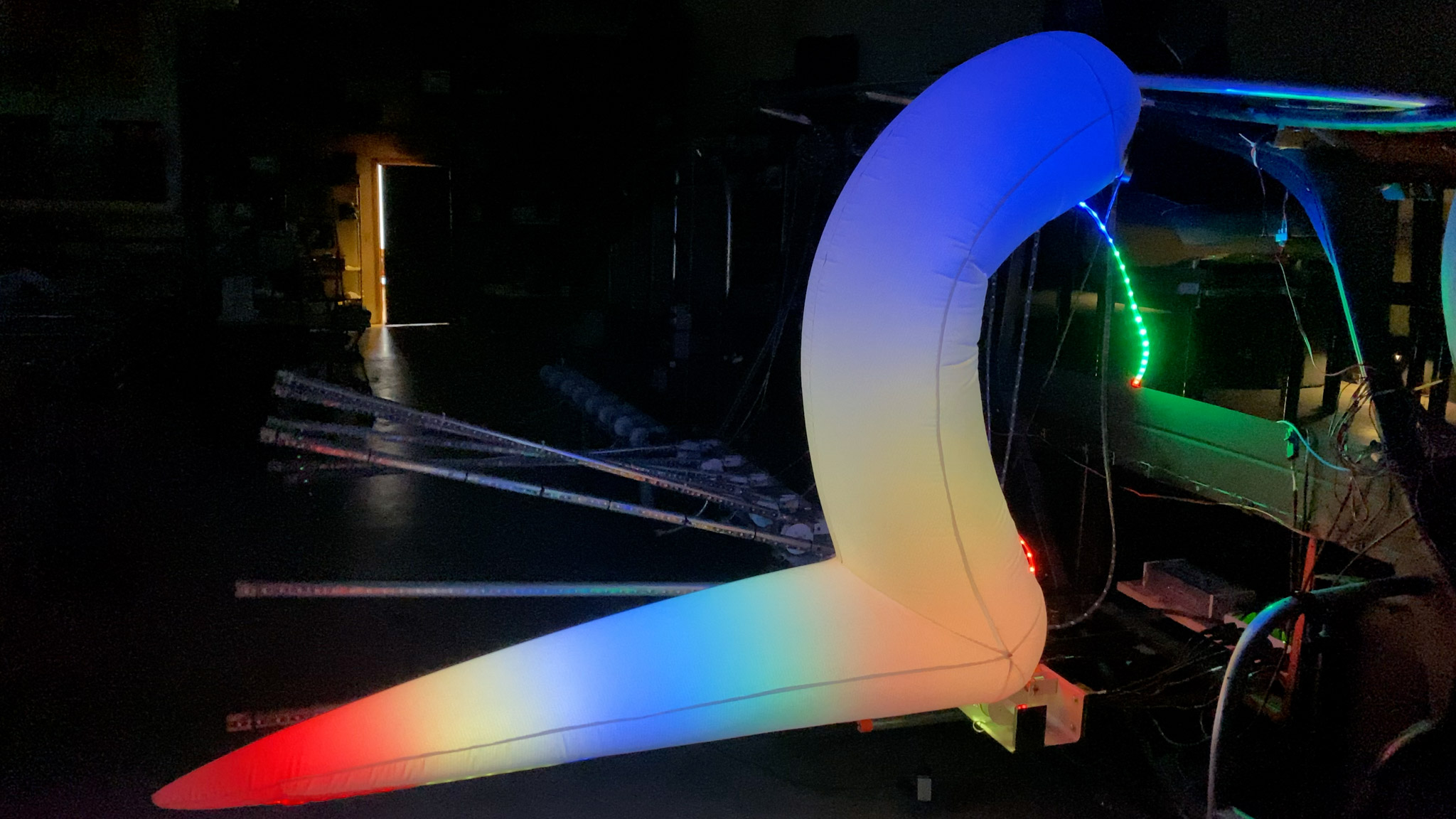

He worked on the shape of the balloon, which would fit over the fins like a sleeve. The shape comes down the body vertically, turns out at an elbow, then extends horizontally. Ideally, he wanted the fins to look flat, not ribbed like an air mattress. Bill builds cold-air inflatables, which are more like hot-air balloons than sealed pool toys. He likes to use quiet, lower-power fans to inflate them.

“Once, we took it for a test drive at 5 miles per hour just outside the shop,” said Bill. It looked good but the tentacles fluttered. “We had to make adjustments like that,” he said.

Mechanical motion

The inflatables that Bill had designed previously were stationary. “This was the first time I had to deal with mechanical motion,” said Bill. The cams run down both sides in two segments — one for the ATV body and one for the trailer — and they didn’t work properly. “We were blowing out motors,” he said.

The poles for the fins were made of metal conduit — too heavy. Loren worked on re-engineering the fins and cam system, along with Skyler Brand, who is a racecar mechanic. They dropped 50% of the weight from the fins and lighting integration. “We were also worried about a bicyclist at Burning Man running into the fins,” said Loren. “By replacing the conduit with a composite PVC tube, with a small 12-inch section of 1-inch aluminum at the drive end, we came up with something lighter, and safer, were someone to contact it on a bicycle.”

“We got things working,” said Brian, “then Bill put some skins on.” The fins began pinching in between the cams. “We blew through three or four different kinds of motors.”

They changed the drive system from direct drive (gear on gear) to the current chain drive, using high-torque, low-RPM, 24V motors. “Skyler’s a real nuts and bolts and gears guy,” said Loren. “We did a lot to make the whole cam system robust and avoid all that extra flex in the cam.”

“The guys who worked on it before, they’re smart guys for sure,” said Loren. “But none of them had been to Burning Man — there’s zero practicality as far as making something durable.” With 11 years of experience at the event, Loren said, “I know the dust and the heat and how it will affect these cams and motors. No way were they going to work for 10-hour shifts in the dirt.”

Lighting system

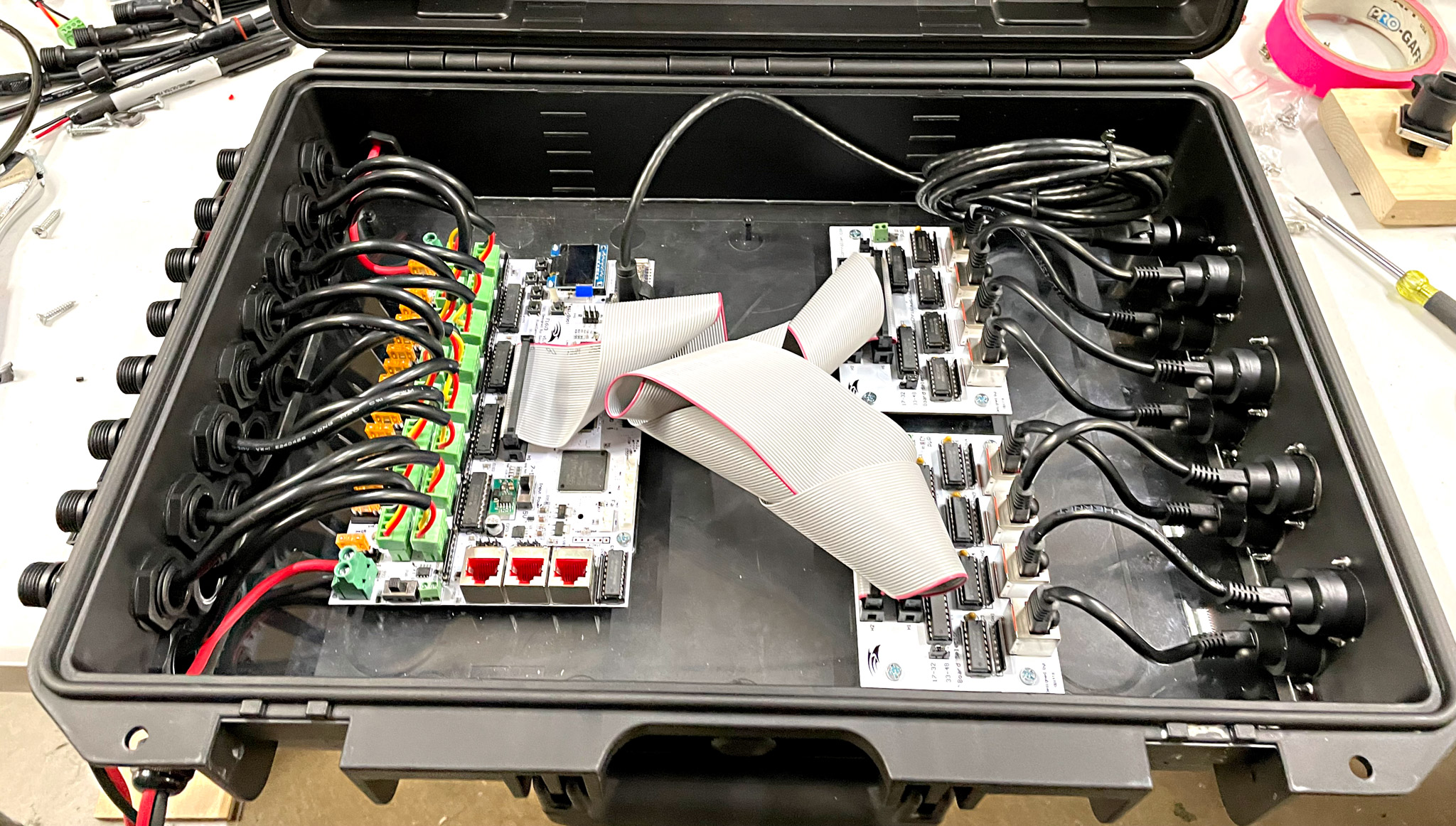

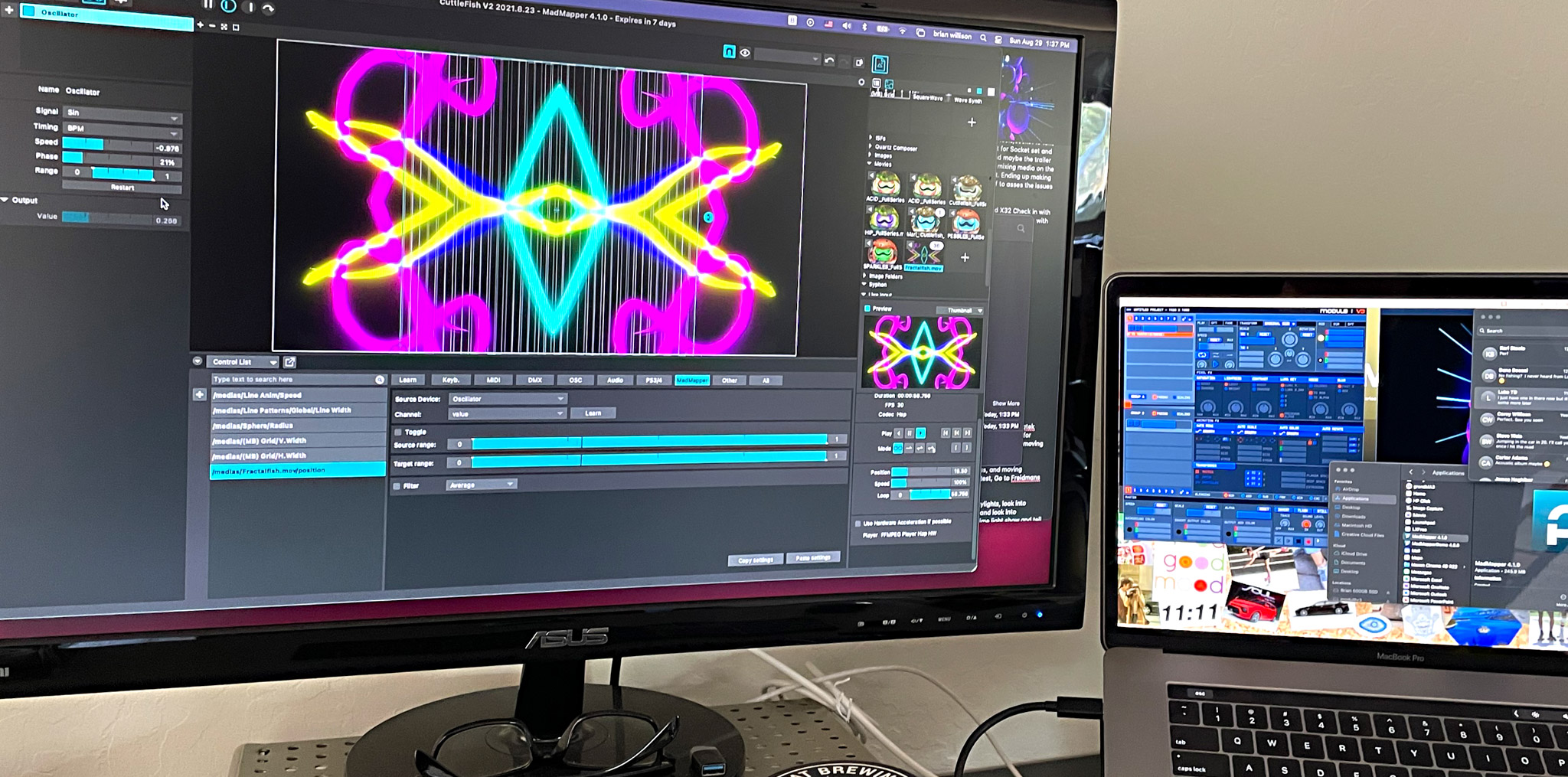

While Bill shaped balloons, Brian figured out how to control the lighting. To replace the proprietary board, he chose the Falcon F16V3, a 16-port smart pixel controller that costs about $250. He decided on a pixel density of 30 per meter and used MadMapper software to do the pixel layout.

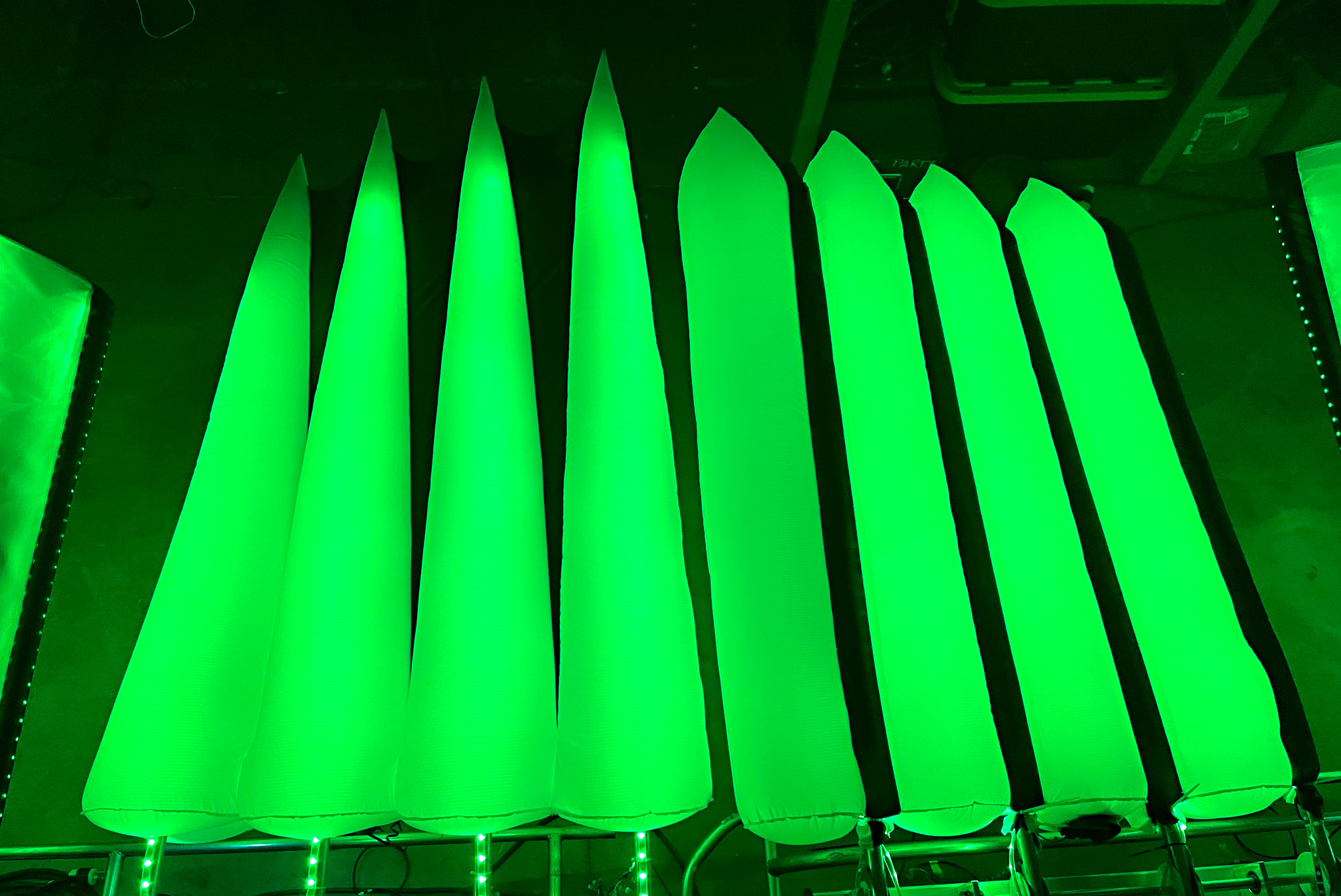

“We went through six or eight different fin designs to see how the lights were going to react,” Brian said. One fin was more triangular and thin; another had a little stubbier head. “What we did was put four of them on, side by side, and ran some light tests and shot videos. Some of the lights are up and down. Some are pointing left and right. They all react a little bit differently. Bill and I worked very closely together for several months to get the diffusion right. One pixel was placed on the tip of each fin.”

The eye

The first idea for the cuttlefish’s round eye was to get a large, clear salad bowl, paint it, and use a short-throw projector for imaging. Bill worried that its images would be shaky, but Brian’s concern was the bulb. “When you have an arc bulb in a projector, as soon as they get dust on them and they get hot and you try to arc them, they’re just going to pop,” he said. They agreed LEDs would be better — but they’d need a hemispheric LED screen. “A curvature with LEDs is still hard to find,” said Brian.

Brian researched some options from China but was worried about shipping time, and returns, if it wasn’t the right solution or didn’t work properly. Then he found a company in Roseville, California, and on their website he saw exactly what he was looking for. Almost.

“What they do is globes,” Brian explained. “But we didn’t need a whole globe; we needed two halves, hemispheres.” Each eye has 77,136 pixels at 2.5mm pitch with 8,000 nits (cd/m2) brightness. The custom job was expensive, said Brian, but he realized the eyes would be the “cherry on top” of the cuttlefish.

Again he turned to MadMapper. “I can just throw an HD file at the processor and it does all of its work inside and spits it out to the eyes. … I’m able to do the eyes and the lighting show simultaneously where one cue controls both.”

Brian also came up with an idea for the exterior of the eye, inspired by a local cannabis club whose designer, Brian Pinkham, had installed a dome-shaped two-way mirror. Bill and Brian liked the idea that during the day, the fish eye would turn into a mirror.

“When I talk to my techie friends and my nerd friends and I show them what we did, it’s always the eye,” he said. “It’s always the eye.”

Battery power

While the ATV is gas-powered, everything else has to run off batteries and generators. The new lighting and camshaft systems changed the wattage requirements. “We were faced with new problems, trying to put our system on top of the original electrical 120V system,” said Loren.

“I bypassed the 120V system and I pulled a bunch of current out of the batteries basically to power all of the 12V systems on the car,” Loren explained. “We were losing over 60% of our wattage by converting from 12V DC from the battery into 120V AC and then back to 12V DC to power the lights. We were going to need over 2,000 watts for lighting, and we’re losing 60% of that wattage because it was done that way.”

Making the tentacles move

“I always thought the head needed to move,” said Loren. “The fins moved on each side but the tentacles on the head were just sitting there.” There are nine arms on the head — three on top and three on each side.

Loren was pushing for robotic movement but Bill thought it might change how his inflatables worked. “There was a lot of fighting about money because so much money had been spent,” said Loren. Eventually, the project manager approved.

“I was able to add three linear actuators and power them with an Arduino Nano using a little individual 12V inverter,” said Loren. “Then I got it programmed to do two functions, opening and closing.” The effect is that the arms open for a person to enter inside and then can gently enclose them.

“That was a huge hit,” said Loren. “People loved it.” He got approval to upgrade to linear servomotors. “Linear actuators will go from point A to point B at whatever speed they go. A servo can actually go from point A to point B over a specific period of time. I was able to make more complicated functions and then have every tentacle articulate individually.” He upgraded to an Arduino Mega.

A final touch was adding a pair of fog machines up front.

The wheels

One more problem: it was a rough ride. “The casters were actually bent and broken,” said Brian. The trailer weight exceeded their rating. Skyler and Loren tried off-the-shelf replacements before finally ordering custom-made casters. “The ride with the first set of narrow casters was extremely bumpy,” said Loren. “We chose a new set of tires that were extremely wide, with a low PSI to cushion the ride.”

To Burning Man and beyond

They had the cuttlefish 90% ready by July 2022. Bill was anxious to be done. He began getting calls from previous clients. “I was having to turn down some fun commissions so I needed to get the cuttlefish out of my shop.”

But first he would give the art car a name. “They were going to call it Cuttlefish 2020 but that’s not how you name things at Burning Man,” Bill muttered. He started with sepia, the Latin name for cuttlefish, and then settled on lux. Sepia Lux, an illuminated cuttlefish. “Lux not only means light in Latin,” he said, but also “lux is a technical measurement of light emitted from a surface.”

Photo by Loren Crotty

He went out to Burning Man to see Sepia Lux at night in the desert. Viewing it from afar on the playa, Bill said to himself, “Holy cow, we created a low rider for Burning Man — low, long, and sleek.” He heard that the patron had a big smile on his face — and he is someone you never see smile. Loren said, “The purpose of the cuttlefish is to make other people happy, and it really did. You could see that.”

Photo by Alicia Williams

At the end of 2022, Loren became leader of the project — Captain of the Sepia Lux. After Burning Man 2023, he brought it to Maker Faire Bay Area in 2023 and 2024.

Photo by Dale Dougherty

Sepia Lux: The specs

“The world’s only inflated, illuminated, articulated, and animated motor vehicle.”

—Bill Kennedy aka Inflatabill

Vehicle

• Heavily modified Polaris General UTV, 1000cc gas engine

• Lifted, upgraded shocks, upgraded clutch

Trailer

• Custom 6’×10′ steel frame trailer

• 4 custom 360° rotating casters with 10″-wide industrial lawnmower tires

• Max capacity 24 persons

Power

• 900Ah @ 48VDC lithium battery bank

• Charging via 2 Honda EU3000 gas generators

• 12kW AIMS inverter, 12 circuits of 120VAC

Sound

• Void Q2 amplifier

• 2 Behringer 15″ subwoofers

• 4 Void 12″ subwoofers

• 4 Void Airten dual 10″ speakers

• 2 Turbosound monitor speakers

Lights

• Falcon F16V3 Pixel Controller board with multiple expansion boards

• 5,000+ individually addressable RGB pixels

• 2 custom LED hemispherical eyeballs with 77,136 pixels per eye @ 2.5mm pitch

• Controlled and mapped with MadMapper

• MIDI control board for manual lighting control

• Wi-Fi iPad interface

Inflatables

• Custom balloons designed and fabricated by Inflatabill

• 911 individual pieces of fabric

• 140 yards of fire-retardant PU-coated ripstop nylon

• 5 air blowers (4 @ ⅛HP and 1 @ ¼HP)

Motion

• 24VDC motors control 4 chain driven cams to rotate 36 fins in a sine wave pattern

• 12VDC linear servomotors and Arduino control motions of head/mouth/arms

• Wi-Fi iPad interface

Dual front fog machines :)

This article appeared in Make: Vol. 90.

ADVERTISEMENT