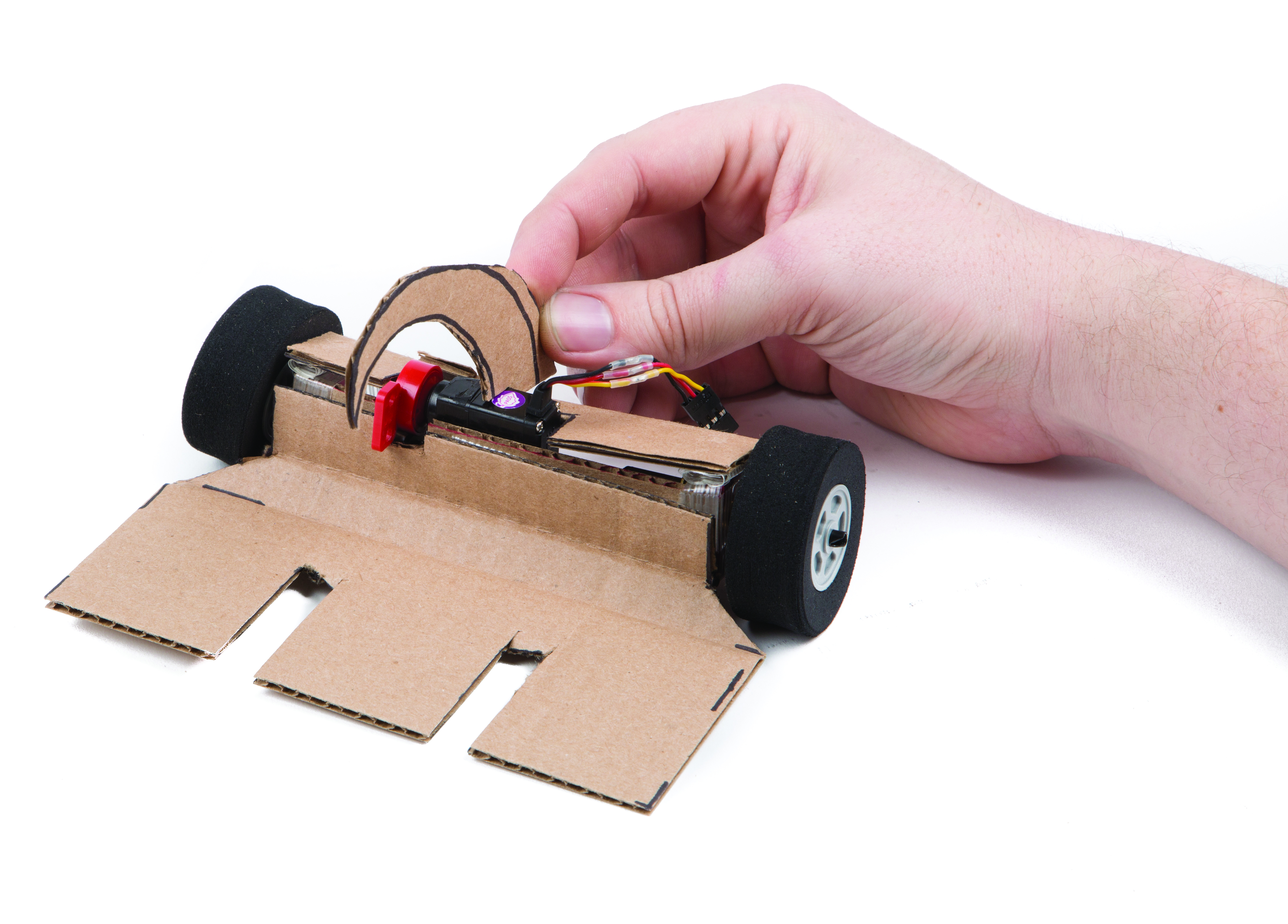

Engineering professors call it “hobby shop engineering,” but my robotics team refers to our design method as “C.A.D.,” nerd code for Cardboard-Aided Design, the low-tech tool for testing new robot designs.

Often, people ask how I get my ideas for making new fighting robots. New designs evolve in many different ways. It could be something I see, think of, dream of, or brainstorm with other people. Ideas can come from handling the materials and from fighting the robots, but you can try various methods.

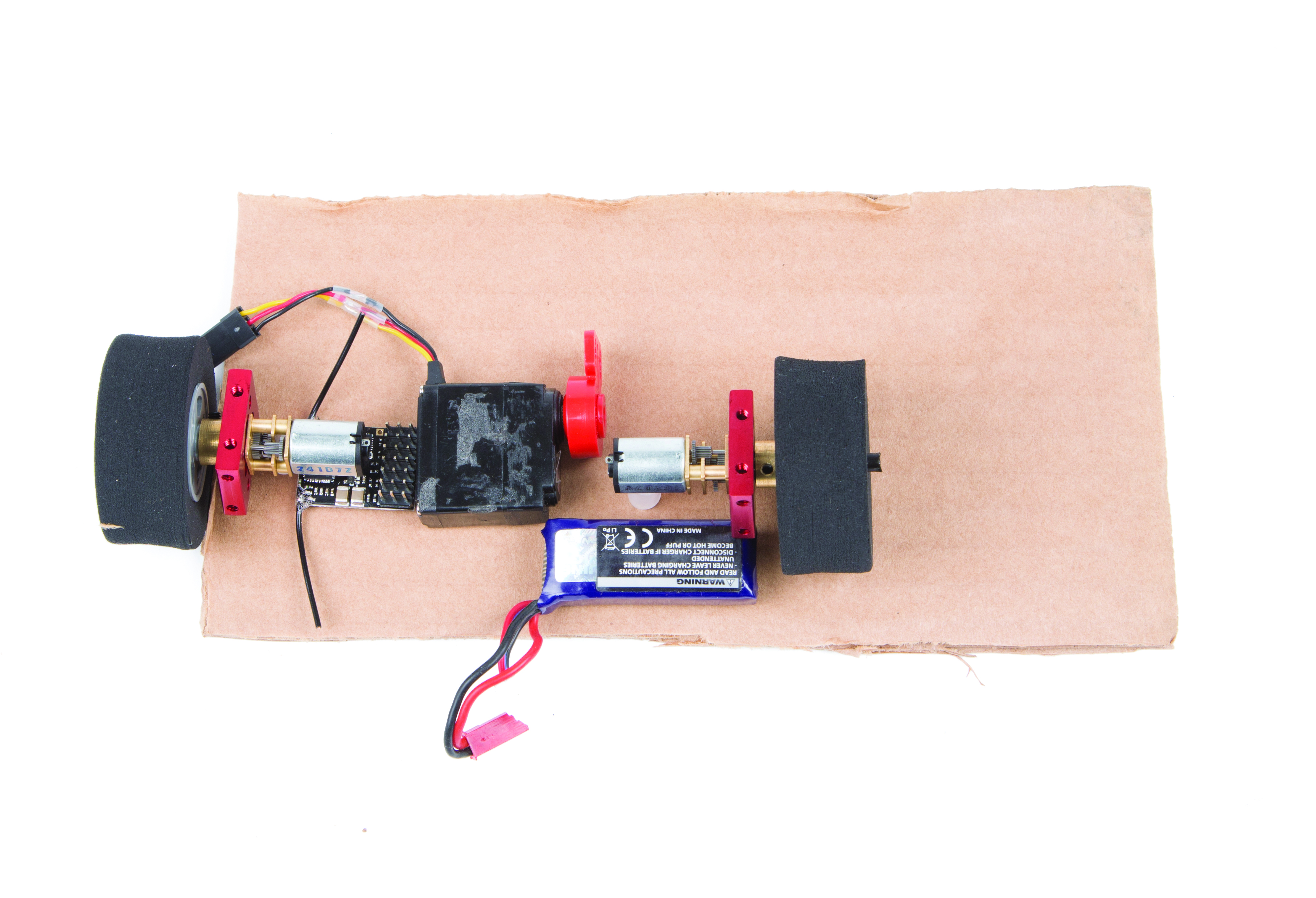

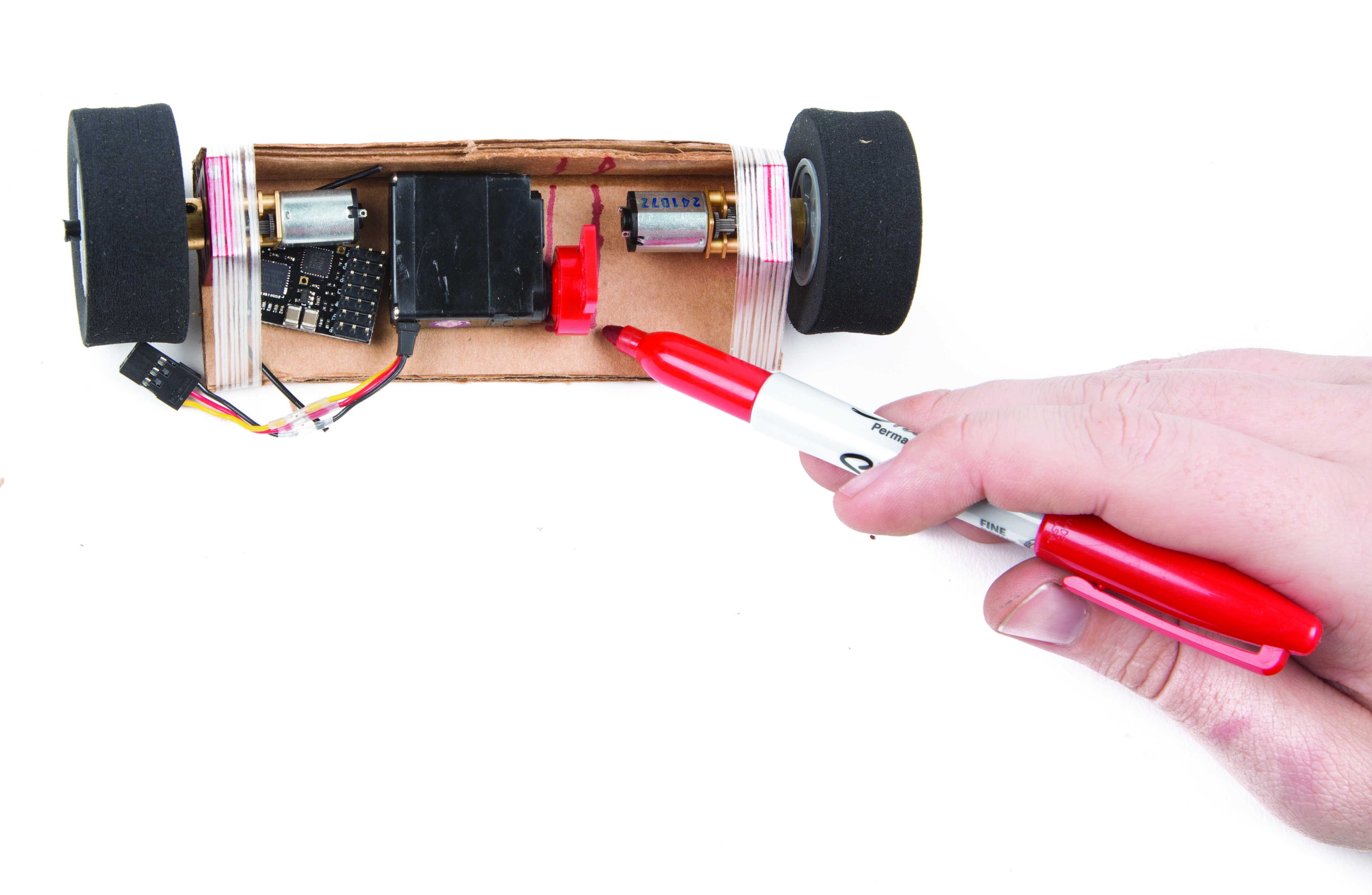

In this process, you draw and cut out the pattern of the parts you plan to use and mock them up in actual size. This way, you can test your ideas in cardboard before cutting out the final materials.

Weigh Your Design Options

There is no one right way to design a robot, but there are some design hurdles to consider. There are endless debates on four wheels vs. two. Should the wheels be exposed or enclosed? Which weapon is best, and do you want more than one? The answers depend what you are comfortable with. Try to build one that fits your personality and drive style.

There will be trial and error. A two-wheeled robot turns quickly and is easy to build, but is difficult to drive straight. A four-wheeled robot turns slower, but is easier to control, and makes it tough for opponents to “high center” you. Exposed wheels can be torn off, but wheel guards can get bent, pinning the wheel. You may be better off losing a wheel and still having three good wheels.

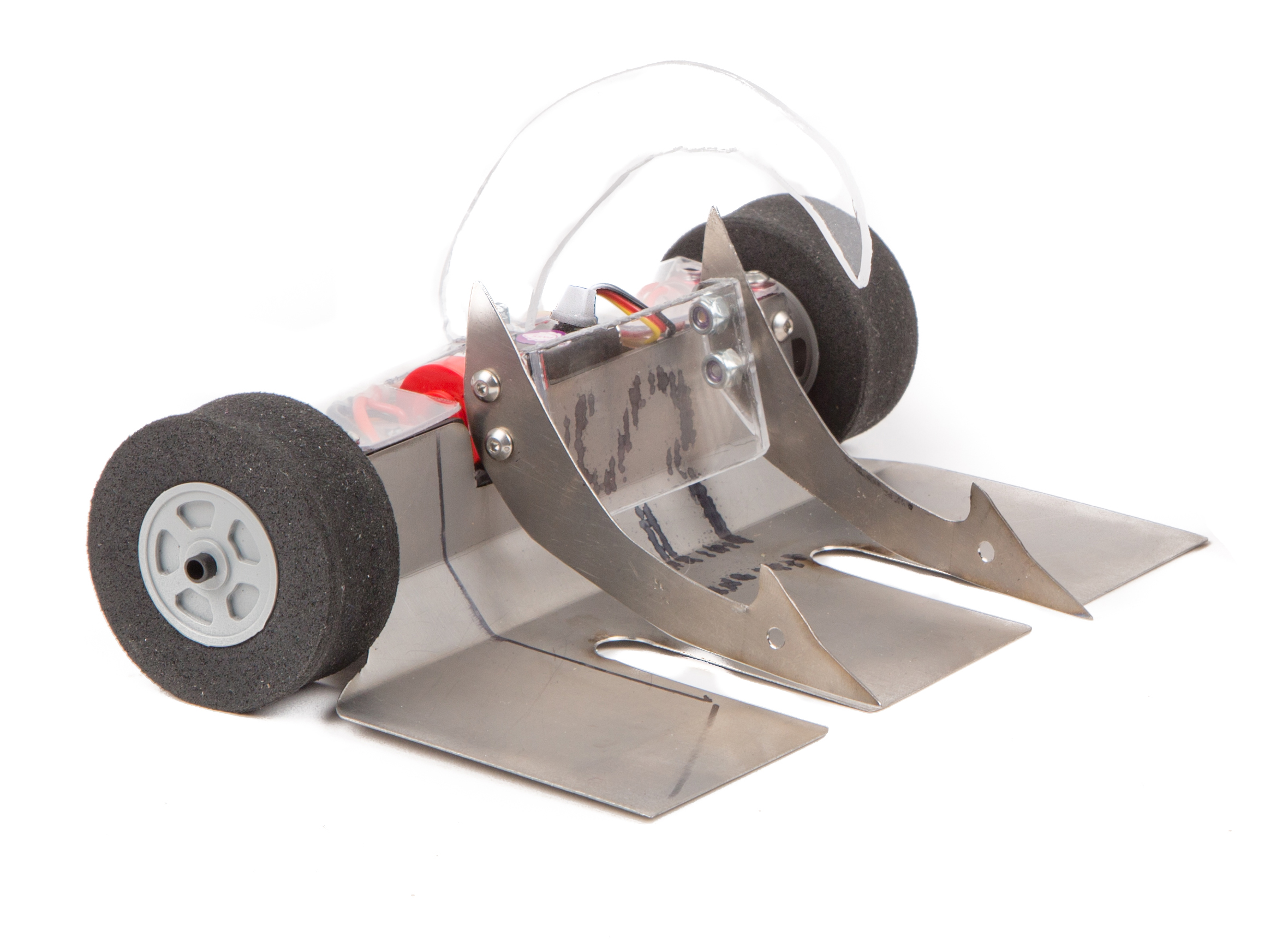

Multiple weapons can overcomplicate the robot or make it too heavy. However, it is highly recommended to always have a wedge — they help get under your opponent and give you leverage. Every great saw, lifter, and crusher has to start as a good wedge. Even if your weapon is completely broken, you can still continue the match as a wedge robot.

Software Versus Paper

I have designed robots with computer models and every part precisely machined, such as The Bomb, which has won four RoboGames’ gold medals. However, for another medal winner — my first champion, named Micro Drive — I used only one piece of cardboard and three pieces of graph paper. This took a fraction of the time the computer models did, and it won two gold medals and a silver. The real question: Would you rather spend your time in front of your laptop, or in front of your workbench?