Once you get past the anxiety of approaching a rapidly spinning chunk of wood with a pointy metal stick, the most difficult part of turning wood on a lathe is understanding your tools. A basic woodturning kit includes anywhere from 5-8 tools, each with their own unique characteristics.

In this guide, I’m going to briefly walk you through the six woodturning tools I personally rely on and present some basics on buying, maintaining, and using these tools. For more information on using the lathe and lathe safety, check out Make: magazine’s writeup on Understanding the Lathe.

A Basic Kit

I recommend that a beginner start by getting a fairly modest chisel kit, learn how to use them, and then slowly add other tools to their collection. You can get most of the results you’re looking for with a kit of around five or six tools.

There are a lot of turning tools out there and a lot of different grinds; don’t worry if you don’t have them all. They’re not like Pokemon — you don’t need to catch them all.

Spindle roughing gouge — The big tool that shifts most of the weight. It can leave a decent finish to the work, but tends to be used mostly to create a ruff shape. It’s the tool of choice for taking a square blank and turning it round. It’s fairly wide (sometimes ridiculously wide) and tends to have a straight grind.

Tip: Never use a spindle roughing gouge on a bowl. If you were to use this tool on a bowl you would risk the tool breaking because the tool has a weak point going into the handle.

Spindle gouge — Sometimes known as a shallow fluted gouge. This is the go-to tool for making details such as beads and coves, and can be used to shape spindle work without much fuss.

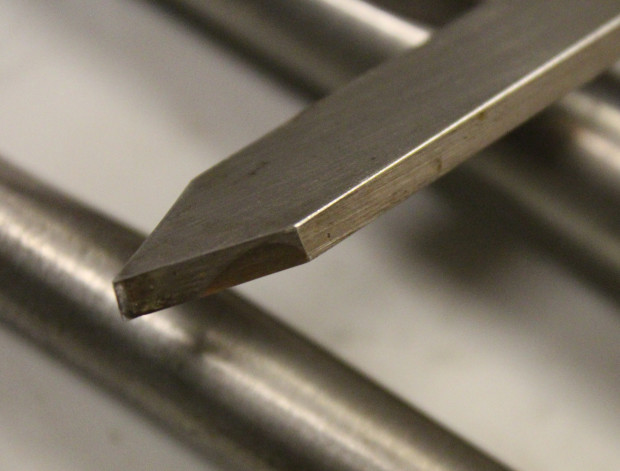

Skew chisel — This tool tends to be used for planing wood. It gives a really good finish from the tool with virtually no sanding needed from the tool. It can be used to create very fine details and, depending on how adventurous you are, it can be used for most jobs.

This tool has a reputation for being difficult and scary, but once you know what you’re doing with it, it is a very useful tool. It just demands a little respect; always give it your full attention. I have only had one injury whilst turning and it was with this tool. It wasn’t a bad injury, but it still happened. Now I am more aware that the skew needs complete concentration.

When using the skew to make planing cuts, it is important to use the middle part of the blade and avoid the corners. If you hit the moving wood with the corner you are likely to get a “catch”. This isn’t the end of the world, but can be a little scary if you’re not expecting it and can ruin your project. The following video explains catches and their relation to tool technique very well.

Parting tool — The clue is in the name; it parts wood. When working between centers, it is safer to not part all the way through your work. Instead, part most of the way and finish the job with a saw. Make sure you turn the lathe off before using the saw.

I have been known to use the parting tool for jobs it’s not designed for, such as a scraping tool. To me, it is an ideal tool for making a spigot for a chuck to hold onto.

Bowl gouge — Also known as a deep fluted gouge. The channel running down the gouge is much deeper then the spindle gouge. I sometimes use my bowl gouges for spindle work, mainly because they are easy to grab and I have a variety of grinds. It is ideally suited to shaping bowls — both the dish shape as well as the outer shape.

Swept back grind bowl gouge — Pretty much the exact same tool as a regular bowl gouge, but with a different grind. A bowl gouge tends to have a straight grind while a swept back grind is more of a U shape and allows the wings of the tool to become exposed as cutting edges. This makes the tool very versatile allowing for a greater range of cuts.

Scraper — These come in different profiles and act in a similar way to a cabinet scraper. Personally, I don’t find them useful and I won’t be covering them in this writeup. Some swear by them, though, so they’re worth researching if you’re curious.

Tip: Saving Money on Tools

You might be tempted into thinking cheap tools will do the job. This isn’t often the case. What makes cheap options a poor choice for woodturning is that the metal is far too soft and doesn’t keep an edge. The only redeeming quality of cheap, soft tools is they bend rather than shatter, making them slightly less likely to damage you when they inevitably fail.

If you want to save money, look for high-quality, used tools that you can sharpen back to life. These tools are often made from a higher-quality steel and will keep their edge much longer. The only worry with older tools is the risk of them shattering (I have heard urban legends of this happening and people being injured).

I highly recommend using a trusted dealer to buy tools and expect to pay between $25 to $50 per tool with the understanding that the tool is likely to last longer than most of the people who would use it.

Sharpening your tools

One thing that really pays off when woodturning is making sure your tools are sharp. Sharp tools lead to better results with less frustration. There are a lot of sharpening systems out there with associate jigs to ensure you can reproduce specific grinds.

I use a slightly adapted Tormek sharpening system which uses a wet grinding stone running at a slow speed. This system is hard wearing and reduces the risk of changing the properties of the metal. I also keep a few diamond honing pads handy to touch up a cutting edge; for me, this feels like I can extend the time between sharpening the tools and works with the hollow grind to give a micro bevel.

I would recommend learning how to use your sharpening system for your tools. Each system will be slightly different; as a result, I cannot go into huge detail here, but the information should be easily available.

Tip: Buying a Sharpening System

My Tormek sharpening system retails for around $1,000 new, but you can find alternative systems for under $200. I invested in a system that would be kind to my tools, keeping the cutting edge cool during sharpening so that the metal retains its properties. I have seen clone versions of my setup for around $500.

Using the tools

There are two main types of turning. The techniques used are somewhat interchangeable, but there are differences to bear in mind.

Spindle work is working between centers. Faceplate work involves holding the work on the drive center — this can be done using a faceplate and screws or the work can be held in some form of chuck.

Preparing for spindle work

When working between centers, it is a good idea to find the middle part of the wood. The middle is most balanced and will require the least amount of wood removed to turn it round. I like to make a mark or dint in the wood at this point, which helps me to locate these points on the lathe.

I would recommend working with the grain in the direction of the lathe, as this makes everything a little easier.

Before starting up your lathe, check that the work rotates freely and doesn’t hit the tool rest. Make sure the wood is securely held between centers and the tail stock is locked in place. It’s super important to make sure the peace is being held securely.

When you are happy that your tool rest is at the right height for you and at a distance appropriate for the blank, you should be ready to work.

Roughing out

To “rough out” is to coarsely define your work’s shape, round off the edges, and give the wood a more even stability. I have known some people to rough out using a number of different tools, but the best one for the job is the roughing gouge (aka the Spindle roughing gouge).

Make sure your tool rest is in a position where it can support your tool and introduce the bevel of the gouge before angling the handle up and introducing the cutting edge.

It is highly recommended that you “work downhill” meaning cut from high points to low points. I would recommend using a stance where you can move easily allowing your body to move the tool rather than just your arms.

Skew

The skew chisel can be used to do a number of different things, but tends to be known for its ability to give planing cuts. I like to raise my tool rest and approach the wood as flat as possible.

Approach the cut with the bevel and try to cut with the middle part of the blade. If you catch the wood with the pointy end of the blade or the other pointy end you’re likely to get a catch. Chances are nothing too bad will happen, but it’s likely to be scary enough to make you want to change your pants.

I also love making super fine detail with the skew. To do this, I use the pointy end like a knife. Making sure the tool is supported, I introduce the pointed end and make a cut. Then I come in from the sides of this cut to neaten the whole thing. You can achieve an unbelievable fineness of detail with this technique.

Spindle gouge

If you mastered the roughing gouge, then this should come easier to you as this is the same idea only at a smaller scale. This is a great tool for putting in pretty details like beads and coves. To make a bead, first figure out where you want the top and bottom part to be. Then as you move the tool along the rest from one point to the other, rotate your tool to introduce more or less of it into the wood, cutting the shape.

Parting tool

Unlike the other tools, there’s no need to introduce the bevel with this fella. You simply introduce it and watch it cut.

The parting tool doesn’t leave behind a smooth finish and it’s not really meant to. I would recommend making two cuts with this tool rather than cutting all the way through; this will reduce friction. If you are “parting off,” I recommend not parting the full way with the parting tool. Instead, finish the job with a saw.

Bowl gouge

There isn’t anything stopping you from using a fairly aggressively ground bowl gouge as a spindle gouge, but in my opinion, the bowl gouge comes into its own when turning dishes.

The bowl gauge can be used in a similar fashion as the spindle gouge, often to cut the outside bowl profile and a tenon. The tenon is a section of wood that protrudes from your project, allowing a chuck to grip onto it from one end. Once a section of wood is mounted in the chuck using this tenon, the bowl gouge can be used to easily form the inside or outside of the dish.

I tend to work from the outside edge inwards when using a standard bowl gouge. I’ll introduce the cutting edge in a line from where the bevel would be rubbing if the bowl extended far enough and cut in towards the center. Eventually the cut will lead to the bevel rubbing more than cutting, providing a smooth surface and a safe operation.

Swept back bowl gouge

This is my favorite type of bowl gouge. With this tool, you have a few more options because of the wings built into its design.

When I am making a dish with the swept back bowl gouge, I will use the wings to cut and then drag back towards the edge of the bowl. If you don’t rub the bevel you might risk a catch or the tool might cut a little more aggressively than you were initially expecting.

Buyer’s guide for lathes

If you are looking for your first lathe, chances are that you have a few questions such as: What is the difference between a $60 lathe and a $6,000 lathe?

The more cash you invest in your tools tends to reflect the quality of the tool and the materials they’re made from, as well as the chance of really useful features. My first lathe cost $50 and it was made from less than fantastic quality parts and as a result was very noisy. This noise was my primary reason for upgrading.

I upgraded to an $800 lathe which is on the more affordable side of the professional lathes and I’ve had a massive success with it. The bearings are quieter and the whole machine is made to a higher standard without any of the cheap and nasty plastic bits that feel as though they’re likely to brake given any abuse.

If you invest more, you are likely to get luxuries such as variable speed controls where you don’t have to change a belt (a real time saver) and a moveable on/off switch, which is a great safety feature. Some machines will offer a longer distance between centers, allowing you to turn items like pool cues and standard lamps. Likewise, there are machines that accommodate wider projects, such as salad bowls and platters.

Generally I abide by the saying that if you buy cheap you buy twice, but you might be able to find a real bargain with a secondhand lathe. I would recommend heading to your nearest woodturning club and asking for advice. A friend of mine was lucky enough to get a secondhand $3,000 lathe for $150 though a local club.

To see my lathe in action, check out the video I made below on the process of creating a custom wooden handle for a friend’s heat press.

ADVERTISEMENT