William Gerrey picks up a leveler tool from his unassuming booth at Maker Faire Bay Area. Levelers are normally tools of the silent variety, but Gerrey has hacked his to emit sound.

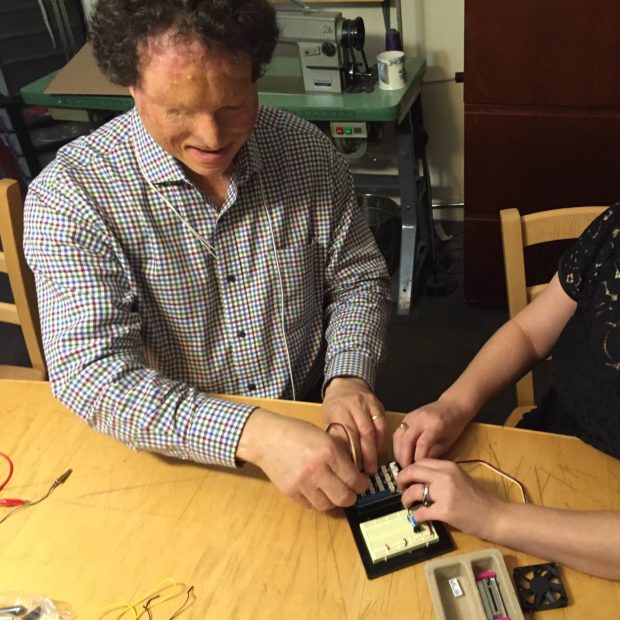

The further it tilts away from being straight, the faster the frequency of its intermittent beeping. Hold it level and the beeping becomes an uninterrupted tone. Gerrey sets the leveler down and finds his seat in front of a soldering gun. Feeling the protoboard with his fingers, he demonstrates how blind people solder.

To walk through Maker Faire is to walk through a sensory overload of visually captivating displays, but not everyone convenes on Maker Faire to see the sights. Gerrey, an electrical engineer who’s been making things for over 40 years, and his colleague Dr. Joshua Miele are both blind Makers. They’ve been tinkering with electronics and engineering their own accessibility hacks for decades. Now, they’ve organized the Blind Arduino Project, the goal of which is to “develop, document, and disseminate techniques by which totally blind Makers can build and share electronics projects” using Arduino.

They also design and publish projects in a way that is more helpful than what’s normally found in project documentation, which “is often done with images or other inaccessible approaches,” says Miele. He recalls that as a teenager he was often frustrated that the only way he could access written instructions for his DIY kits was to have someone read them aloud to him. Unbeknownst to Miele at the time, Gerrey was working on a Braille magazine for blind electronics enthusiasts.

“Not only did The Smith-Kettlewell Technical File offer step-by-step instructions on how to build the accessible test equipment that I lacked,” writes Miele, “it also offered tutorials and recommendations on non-visual approaches to circuit design and soldering. The DIY projects… did not include circuit diagrams. Instead they used highly standardized, recipe-like, verbal circuit descriptions which allowed blind readers to independently assemble electronics projects.”

For the past three decades, Miele has been following in the footsteps of the Smith-Kettlewell Institute, pushing the boundaries of blindness accessibility. He works on enhancing screen readers, auditory displays, audio/tactile maps and graphics, wayfinding, braille input, and video description.

Miele thinks of blind tinkerers as meta makers. “We make the tools we need to make the things we want to make,” he explains. Various disparate accessibility hacks and the people who benefit from them have coalesced recently within the Maker Movement, but blind people have been meta making since long before the Maker Movement had a name. Gerrey, for example, developed his sonic leveler back in the 1980’s. And Miele notes that there is a large presence of blind radio operators in the HAM radio community.

While Miele and Gerrey have made great strides for blind and DIY communities, Miele says there’s still lots of work to be done. “Prejudice and the low expectations of others are often the greatest roadblock to blind kids succeeding in STEM,” he says.

“I think the most important thing for non-disabled makers to remember is that if they want to help blind people, or people with other disabilities, by using their maker skills, the principles of user-centered design are critical. You can’t design something to help people if you don’t understand what help they need. Waiting until you have a prototype to begin getting feedback is way too late.”

He’s previously compared this to designing a sailboat only after you’ve actually sailed on one. Otherwise you’re likely to have very little insight into how and why certain design choices are made.

So, if you’re setting out to build a boat, it’s helpful to know how the waves feel. And thanks to Miele and his work with the Blind Arduino Project, those waves have become much easier to navigate!

ADVERTISEMENT